PANEL: A Generous Asylum System Riddled with Fraud:

http://us4.campaign-archive2.com/?u=11002b90be7384b380b467605&id=b96545155e&e=50abfffa13

WASHINGTON, DC (April 28, 2014) — The Center for Immigration Studies will host a panel discussion to explore fraud and abuse in the asylum system. The erosion of controls designed to prevent fraud, and the resulting increase in approvals, have led to a 600 percent increase in applications since 2007.

This has serious implications for ordinary immigration control, as seen in South Texas, where there is a surge of Central Americans crossing illegally many of whom are claiming asylum. It also has national security implications; not only were the Boston Marathon Bombers granted asylum, but the Obama administration announced earlier this year that it was loosening restrictions on asylum seekers with ties to terrorism.

Panelists will also discuss the potential impact of the Senate immigration reform bill on the asylum system as well as feasible reform proposals.

Date: Wednesday, April 30, 2014, at 9:30 a.m.

Location: National Press Club, 529 14th Street, NW, 13th Floor, Washington, DC

Participants:

Dan Cadman, Former INS / ICE official with 29 years of experience as an agent, supervisor, and manager and author of a new CIS report, “Asylum in the United States: How a finely tuned system of checks and balances has been effectively dismantled”

Michael Knowles, President, USCIS Local 1924 of the American Federation of Government Employees

Jan Ting, Former INS executive overseeing asylum; currently Temple University Beasley law professor and CIS board member

Moderator: Mark Krikorian, Executive Director, Center for Immigration Studies

View the new CIS asylum report at: http://www.cis.org/asylum-system-checks-balances-dismantled

Asylum in the United States

How a finely tuned system of checks and balances has been effectively dismantled

On December 13, 2013, the Los Angeles Times carried the story “Immigration claims for asylum soar”, with a rather astonishing lede:

The number of immigrants asking for asylum after illegally entering the United States nearly tripled this year, sending asylum claims to their highest level in two decades and raising concerns that border crossers and members of drug cartels may be filing fraudulent claims to slow their eventual deportation.1

A primary genesis of the article was a report by Ruth Ellen Wasem of the Congressional Research Service (CRS)2 showing that grants of “temporary asylum” jumped from 13,931 to 36,026.3 Her report was submitted for the record during a December 12, 2013, House Judiciary Committee hearing, “Asylum Abuse: Is It Overwhelming Our Borders?”

But fuel was added to the fire when Border Patrol officials were cited in the news article expressing concern that narco-trafficking cartel members south of our border might be availing themselves of asylum benefits through fraudulent claims. There is reason to take this concern seriously.

Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), Chairman of the committee, had this to say during the hearing:

Currently, data provided by DHS show that USCIS makes positive credible fear findings in 92 percent of all cases decided on the merits. Not surprisingly, credible fear claims have increased 586 percent from 2007 to 2013 as word has gotten out as to the virtual rubberstamping of applications.4

Key Findings

This report examines our asylum system, the increase in applications and approvals, and the erosion of checks and balances designed to prevent fraud that have contributed to that increase.

Key findings include:

- Offering refuge to the persecuted is a long-established and valued American tradition, with a process inscribed in law and reinforced by international treaties. The United States operates one of the most generous asylum systems in the world, receiving about one out of every six claims filed.

- The “credible fear” test is the key that unlocks the gate leading to asylum and permanent residence in the United States. Today, 92 percent of asylum applicants pass this test. The number of individuals passing this critical test nearly tripled from 2012 to 2013, and has increased nearly 600 percent since 2007.

- Over the years, Congress and the executive branch have implemented provisions designed to stem fraud and abuse of the asylum system, but these have become less viable over time. Some have been undone by executive action or policy and others whittled down by judicial decisions.

- Notably, the statutory mandate to detain asylum seekers until their credibility can be established has been largely ignored, according to a leaked DHS report to Congress on the subject.

- Another report on the results of an innovative program to detect fraud in asylum applications found that only 30 percent of applications could be confirmed as fraud-free, while 70 percent were confirmed fraudulent or had strong indicators of fraud. This report was suppressed by the Obama administration, which has discontinued the fraud-finding audits.

- A series of judicial rulings has expanded the boundaries of approvable asylum claims, which further encourages aliens to apply — increasing the likelihood of fraud. More concerning, these rulings have created opportunities for dangerous individuals, such as gang members, cartel operatives, and even supporters of terrorist groups to qualify for asylum, despite involvement in crime and violence that would otherwise be grounds for exclusion or deportation.

- The comprehensive immigration bill approved in 2013 by the Senate included a long list of proposed changes to the asylum system that would dismantle the few checks on fraud and abuse that remain. These include allowing previous asylum fraudsters to re-apply and qualify and allowing asylum to be granted instantly upon application, before any vetting of the applicant occurs.

- The reasonable reforms proposed in this report can be implemented by Congress and the executive branch to balance our interest in providing refuge for genuine applicants while deterring those who seek to exploit our welcome to the oppressed. These include curbing further expansion of the protected grounds for granting of asylum; removing incentives for fraud; auditing to detect fraud; establishing additional bars to asylum for individuals (such as gang members) who victimize others; and mandating that government officials investigate, prosecute, and penalize those who abuse the process.

Background

Ever since men have bonded together into civil societies, two notions have been present in those societies in one form or another: exile and sanctuary.

Exile generally involved someone being cast out of society for conduct or expressions of thought contrary to that society’s norms. Sanctuary represented its obverse, someone fleeing the reach of a society for crimes real or perceived, usually to another land.

Oddly, though, sanctuary in the ancient world sometimes consisted of flight to a particular, acknowledged spot physically within the society’s boundaries, but nonetheless deemed outside of its reach — usually a site held to be sacred to the gods, and thus not subject to man’s rules. Concepts of the inapplicability of civil law within the religious realm, however, continued well into the development of European nations, with the Mother Church not only enforcing its own set of laws, at times with terrible effect (witness the Inquisition), but also providing in its churches, monasteries, and elsewhere places of refuge from the monarch’s sometimes inflexible and arbitrary application of law.

Modern notions of sanctuary have come down to us from those ancient origins, and are now embedded in a variety of international laws and treaties. The term of art used in these treaties is non-refoulement, or non-return. The operative principle is that nations have a duty not to return victims of persecution to their persecutors. The United Nations has a robust governing body charged with overseeing their implementation, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Forms of Non-Return Found in U.S. Immigration Law

Although this report is specifically about asylum, it is important to understand the underpinnings of non-return in all its forms. The United States is signatory to several international agreements relating to non-refoulement and, by way of rendering them effective, has embedded them in particular sections of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Non-return takes several forms within the INA:5

- Refuge (“Refugee Status”)

- Asylum

- Withholding of Removal (deportation)

- Relief under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (commonly referred to simply as the Convention Against Torture, or “CAT”)6

There are also some additional niche “safe haven” programs provided for by law that are not cognizable under international agreements, but that have grown out of our involvement in theaters of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. The general outline of these programs is the same: to provide for the possibility of resettlement in the United States for individuals and their families who have provided assistance to the U.S. armed forces or civilian agencies operating in those countries.

Refuge. The granting of refuge — formally granting an individual status as a refugee — under United States immigration laws is authorized by Section 207 of the INA, although the definition of a refugee is found earlier in the Act, at Section 101(a)(42).7 That section, and its implementing regulations, codify the particular grounds of persecution that must be established before an individual is granted refuge.

Refugees are generally people outside of their own country who are unable or unwilling to return home because they fear serious harm.8 In the context of our laws, a person must be outside the boundaries of the United States to apply for refugee status. In addition to the five grounds, as laid out under international treaty and the INA, the United States recognizes certain other, specific, classes of people as entitled to apply for refugee status based on amendments written into federal law (the Lautenberg Amendment and the Specter Amendment).9

Asylum. The granting of asylum is authorized by Section 208 of the INA.10 The grounds for granting asylum are precisely the same as those for granting refugee status. However an individual seeking asylum is either already physically within the borders of the United States or at its threshold, for instance at an air, land, or sea port of entry.

It is noteworthy that, unlike individuals granted lesser non-refoulement protections such as withholding of removal and Torture Convention relief, both asylees and refugees are entitled to apply for adjustment to lawful permanent residence one year after the date of grant of their initial status.11 As can be imagined, this fact is a strong incentive for individuals who have no other possible method of obtaining the right to live and work in the United States to attempt to gain refuge or asylum by whatever means necessary, including through filing of fraudulent claims.

Withholding of Removal and Convention Against Torture. Withholding of removal is authorized by Section 241(b)(3) of the INA.12 It is a lesser form of relief than asylum and provides no path to resident alien status. It is granted to individuals who are ineligible for asylum, either because they did not apply in a timely manner or, frequently, because they are barred from asylum for having committed certain acts or crimes. To obtain withholding, they must show a fear of persecution under the same grounds used to adjudicate asylum applications. In the discretion of the immigration authorities, the deportation of such persons, despite their adverse history, may not be required if to do so would put them at substantial risk of death or serious harm, although particularly serious crimes or proof that the applicant is a persecutor will still render aliens ineligible for withholding.

But even in the worst circumstances, say that the individual is a war criminal or terrorist, he or she may still be entitled to protection under the terms of CAT. This is a last-ditch protection for the even the most vile among us, insofar as signatories to the convention have affirmed their belief that no one should be subjected to torture. Once the terms of the convention have been found to apply to an individual, the options for the alien’s deportation are limited to either receiving and accepting assurances from the country of return that his or her conditions of return will be humane13 or finding a different country to which he or she will be admitted, a difficult proposition when the person in question is himself a terrorist, war criminal, or persecutor.14 These alternatives are rarely available for obvious reasons and strenuously opposed by human rights groups.15

It should be noted, though, that the federal government’s failure or inability to use them more frequently puts it in the invidious situation of either placing such an individual into indefinite detention (a near impossibility in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in Zadvydas v. Davis, in which the court stated “We have found nothing in the history of these statutes that clearly demonstrates a congressional intent to authorize indefinite, perhaps permanent, detention.”)16 or, on the other hand, appearing to harbor and coddle the worst of mankind by releasing such malefactors into society.

The Five Grounds for Asylum

The designated grounds for granting asylum are precisely the same as those for individuals seeking to obtain refugee status.

Under international agreements, and as embedded in federal immigration law, “Refugee status … may be granted to people who have been persecuted or fear they will be persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, and/or membership in a particular social group or political opinion.”17

Readers should also note that there is absolutely no provision for seeking asylum based on economic circumstances, no matter how severe. This is, in a way, a curiosity in that it provides no avenue of relief for starving families in drought- or war-stricken regions, even where widespread famine and death prevail. In another sense, though, it is a pragmatic recognition that were economic privation to provide a basis for refuge or asylum, massive movements of people would result in destabilization of many governments the world over.

While the five enumerated grounds appear reasonably straightforward at first blush, they become a tangled web on further consideration because they are not further defined. For instance:

- How does ethnicity play within the context of the specified grounds of race and nationality?

- What about individuals who are of the same race, ethnicity, and perhaps even nationality, but are of differing, or minority, tribes or clans? Do they merit protection from the majority?

- Does gender or sexual orientation merit protection, even though neither is mentioned in the five grounds?

- What does it mean to have a political opinion? And what if that opinion is odious to the majority?

These are the questions that have plagued executive branch officials, tribunals, and courts since enactment of the laws covering asylum — and that have, in more than one instance, opened the door to administrative and judicial activism in defining “social group” and “political opinion” in ways that were never conceived by our leaders and legislators when signing the agreements or codifying the enacting statutes.18 And, it must be said, interpretations that have led to grants of relief under the asylum and related laws often reflect the views of the prevailing administration, right or left (to the extent those phrases have meaning in the immigration context), which inevitably appoints leaders to its immigration agencies whose moral and social views are consonant with the president’s.

The Distinction Between Asylees and Refugees

Although the grounds for claiming asylum are the same as those for seeking refugee status, there are some singular differences in law and regulation and, consequently, also in the review and adjudication processes used.

This gives refugee/asylum officers, members of a specialized division within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the immigration benefits-granting arm of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), a bit more say in who is interviewed, when they are interviewed, and whether, or when, they will be permitted to enter the country.19

By contrast, there are no numerical ceilings for asylum; consequently it is in some ways more subject to abuse since anyone within the boundaries of the United States, or at its doorstep, may make a claim.

Seeking asylum is a multi-step process. What is more, there are “affirmative” claims and “defensive” claims, each of which has a somewhat different process because of how they come about.

Affirmative vs. Defensive Asylum Claims

Affirmative claims begin shortly after an individual’s arrival because he presents himself to a DHS officer (sometimes, but not always, a CBP inspector at a port of entry) or appears at a USCIS office to make the request, file the appropriate forms, get fingerprinted and photographed for registry and background inquiry purposes, await an interview, await the results, etc. It is a lengthy process because there are inevitable delays in interviews and decisions owing to backlogs. These delays work to the advantage of fraudulent and frivolous claimants because, even if they are ultimately denied, if they can at least pass the preliminary credible fear test, they buy themselves many months, often years, living and working legally in the United States while awaiting their formal asylum interview and the subsequent decision.

But in every case, a grant of asylum in the affirmative context is predicated on a key initial finding: An individual must establish to the satisfaction of a USCIS asylum officer that he has a “credible fear” of persecution in his country of nationality or habitual residence. A determination by the officer that the fear is not credible usually results in serving of charges alleging that the individual is removable from the United States and requiring that he appear before an immigration judge to adjudicate the charges. The same is true if, ultimately, there is a denial by USCIS officers of the formal asylum claim subsequent to the credible fear finding.

In such cases, the individual may renew his application for asylum with the presiding judge, who will be obliged to adjudicate the request for asylum in tandem with the charges alleging inadmissibility to the United States (some of which could conceivably also act as a bar to asylum depending on their severity, such as in the case of conviction for particularly serious crimes).

In port-of-entry cases, the CBP inspector will defer admitting the individual to the United States once an asylum request is made and initiate contact with USCIS so that a credible fear claim may be reviewed by asylum officers. If the asylum officer determines that the claim is not credible, the individual may be permitted to withdraw his application for admission and depart. If he wishes to pursue the request for asylum, it becomes a defensive case because it can only be reviewed in the context of a removal hearing in immigration court. Exclusion charges will be prepared and the individual served with notice to appear before an immigration judge, just as with an alien who sought the benefit unsuccessfully with USCIS.

Defensive claims also come about as the result of apprehension at or near the nation’s external boundaries by the Border Patrol, whose agents form a division within CBP, or by ICE agents within the interior. In these cases, as in the affirmative cases described earlier, the individual may renew his application for asylum with the presiding judge, who will be obliged to adjudicate the request for asylum in tandem with the charges alleging inadmissibility to, or deportability from, the United States.20

Even interdiction of intended migrants in international waters by the U.S. Coast Guard (also a DHS component) can result in a formal application for asylum if, as the result of “asylum pre-screening” conducted on board the Coast Guard vessel, there is a finding of credible fear.

A description of the affirmative and defensive processes, and a table contrasting them, can be found on the USCIS website although, as can be seen from the examples given, there is an elasticity between the two that defies easy categorization of either one.21

Credible Fear vs. Well-Founded Fear

Passing the credible fear test is to leap a major hurdle in one’s pursuit of asylum. And even if one’s application for asylum ultimately fails, in the interim there most likely has been a long hiatus (consisting of months, not infrequently years) between a finding of credible fear and a final denial of asylum, during most of which the individual has almost certainly been at liberty, has been working if he so chooses, and has had more than enough time to become familiar with his surroundings so that, if the final decision is negative, he can simply melt into society rather than face the possibility of expulsion.

But credible fear alone is not the full litmus test. An applicant must establish that he has been the victim of past persecution, or that he faces a “well-founded fear” of future persecution. Establishing well-founded fear imposes a higher burden of proof on the applicant than credible fear, but establishing credible fear is a good first step.

Exactly what constitutes a “well-founded fear” has been the subject of innumerable precedential administrative and judicial cases. According to the Immigration Judge Benchbook, “The applicant’s ‘desire to avoid a situation entailing the risk of persecution’ may be enough to prove a well-founded fear and thus, establish eligibility for asylum relief.”22

Some scholars believe that a one-in-10 chance of persecution is adequate to establish a well-founded fear. This belief is based on the language used by Justice Stevens in issuing the Supreme Court ruling in INS v. Cardoza Fonseca: “There is simply no room in the United Nations’ definition for concluding that, because an applicant only has a 10 percent chance of being shot, tortured, or otherwise persecuted, he or she has no ‘well founded fear’ of the event’s happening.”23

Much of the determination as to whether an applicant has met the “well-founded fear” standard rests on two prongs: the adjudicator or court’s assessment of his credibility, combined with what is known about circumstances involving human rights violations or persecution in the country he has left. These circumstances are known as “country conditions”.

Applicant Credibility. Because in many, perhaps even most, cases, an individual cannot prove with direct evidence that he has been a victim of past persecution or that he will be subject to future persecution sufficient to meet the well-founded fear standard, great weight is given to his testimony, demeanor, factual representations, etc. Unfortunately, the weight given to credibility is so well known among aliens, shadowy third parties, and the less-scrupulous practitioners of law, that it has bred a virtual cottage industry of “coaches” who assist in putting together facially credible tales of persecution to be used in the individual’s formal application and face-to-face interview when summoned by the authorities.24

Country Conditions. Applying what is known of country conditions to individual cases has become so important that, in addition to yearly publications by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the U.S. Department of State, there are a plethora of publications of varying degrees of use and, frankly, accuracy that are promulgated by various nongovernmental organizations and immigrant advocacy groups.25

Other Hurdles

There are other hurdles, of course, to obtaining asylum, such as if the applicant:

- Was firmly resettled in a third country prior to seeking asylum in the United States, or can be safely removed to a third country under bilateral agreements;

- Has been convicted of a “particularly serious crime”;

- Has committed a “serious nonpolitical crime” outside the United States;

- Has engaged in or supported terrorism, or is likely to do so, represented or maintained membership in a terrorist organization, or incited terrorism or received terrorist training;

- Ordered, incited, assisted, or otherwise participated in the persecution of any person on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion;

- Is a danger to the security of the United States; or

- Is the spouse or child of an individual who is inadmissible for any of the above reasons within the five years prior to making application for asylum.

Regrettably, many of the terms used by these bars, such as “particularly serious crime” and “serious nonpolitical crime”, are not defined by law, as a result of which administrative, appellate, and judicial entities have developed a body of constantly evolving precedential decisions interpreting what they mean.

Some of those interpretations appear to stand logic on its head in carving out exceptions to the legal bars that have resulted, or will likely result, in grants of asylum to individuals whose presence in the United States is not in the public interest.

A prime example is the administration’s recent use of “executive action” to sharply circumscribe the material support of terrorism bars to the granting of refugee or asylee status. This was done by a “Notice of Determination” promulgated on February 4 in the Federal Register, the official publication of the United States government, without providing an opportunity for public comment by experts or interested parties. Although administration spokesmen down-played the significance of the notice and the circumstances under which it would apply, when juxtaposed against the specific provisions of law enumerated, it clearly indicates the government’s intent to apply a waiver across a broad spectrum of serious terrorism activities.26

Scope of the U.S. Asylum Program

The United States administers one of the most generous asylum programs in the world.

In a March 2013 report, the UNHCR stated that in 2012, for the seventh year in a row, the United States led a list of 44 nations in receipt of asylum requests, accounting for one out of every six claims filed.27

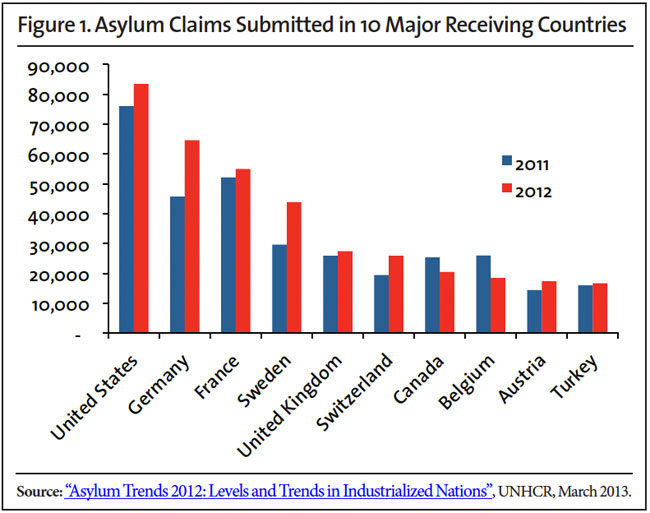

Figure 1, whose data were taken directly from the report, shows the relative rankings among the top 10 receiving nations.

The UNHCR report goes on to state about the 2012 U.S. asylum statistics:

An estimated 83,400 individuals submitted an application for asylum, 7,400 claims more than the year before. Asylum seekers from Egypt (+102 percent), Honduras (+38 percent), Mexico (+35 percent), and Guatemala (+24 percent) accounted primarily for this increase. Almost half of all asylum claims in the country were lodged by China (24 percent), Mexico (17 percent), or El Salvador (7 percent).

Calculated as a percentage, the 7,400 increase from 2011 to 2012 that is cited above constitutes a rise of almost 10 percent in the number of applications filed in a one-year span.

Scope of the U.S. Asylum Problem

Congress and the executive branch, recognizing not only the potential, but the reality, of abuses in the past have over the years attempted to minimize those opportunities for abuse by amending various statutory and regulatory provisions, including:

- Establishment of a one-year-after-arrival deadline for the filing of a request for asylum;

- Institution of a pre-decisional threshold decision about the credibility of one’s claim (called the “credible fear” test);

- Detention of asylum applicants while their claims are pending; and

- Decoupling of asylum claims from automatic and immediate grants of work authorization.

Many of these provisions were embedded into the INA by amendments made as a part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA). They were designed to restore integrity to a system that was badly abused in the early 1990s, when innumerable aliens flushed their travel documents down airplane toilets while en route to the United States, only to make fraudulent claims at their port of arrival (often Kennedy Airport in New York) and walk out the doors of the international arrivals area and disappear, having successfully accomplished their aim of achieving a de facto legal status regardless of the ultimate outcome of the asylum claim. The claims became so notorious that in March 1993 the CBS show “60 Minutes” aired a segment exposing the extent of the fraud to the American public; the segment in turn generated a significant amount of publicity and commentary28 and, ultimately, congressional action.

Among those who availed themselves of the lax asylum policies of that era were Mir Aimal Kasi (a.k.a. Kansi), who arrived in 1991 and two years later murdered and wounded several CIA employees who were queued up in their vehicles waiting to enter the agency’s secure compound. Another was Ramzi Yousef, international terrorist, conspirator, and perpetrator of the first World Trade Center bombing in New York, and associate of the infamous “Blind Sheikh”, Omar Abdel Rahman, another international terrorist who is now serving a life sentence in federal prison in the United States.

While the checks and balances established by the asylum amendments would appear robust, the fact remains that they act as deterrents to fraudulent or frivolous claims only to the extent that they are used and viable, and there is significant reason to believe that they are increasingly less viable, as memories have faded about the abuses of two decades ago.

The One-Year Deadline for Requesting Asylum. IIRIRA amended the asylum laws to require that an applicant establish “by clear and convincing evidence that the application has been filed within one year” after his arrival in the United States.

However, an exception to this rule was carved out that can open the door to abuse or dilatory tactics, in that it simply requires an assertion of changed or extraordinary circumstances.29 If the adjudicating officer agrees, then the application is accepted without regard to the length of time that has passed beyond the one-year deadline.30

The “Credible Fear” Test. There is also cause for worry about the present upward trend with regard to the sheer numbers of individuals making credible fear of persecution claims, particularly since, as Rep. Goodlatte observed at a committee hearing in December, DHS data show that in recent years 92 percent of claims have resulted in a finding of credible fear.

An approval rate that high suggests a bureaucracy within USCIS that is philosophically unwilling to, operationally incapable of, or politically fettered from wise exercise of its responsibility to mitigate abuse of a system extremely susceptible to fraud and false claims. Such findings effectively nullify the point of a credible fear test, and significantly undercut public and political confidence in the asylum program.

One cannot conclude that the world has become so much more unstable in the course of a year. It is no wonder that there are deep concerns that the program is rife with opportunism and fraud. Even as this report was being written, an article appeared in the Washington Times, which, like the Los Angeles Times, carried a shocking lede:

At least 70 percent of asylum applications showed signs of fraud, according to a secret 2009 internal government audit that found many of those cases had been approved anyway.31

At the second House hearing on asylum held on February 11, retired USCIS official Louis D. Crocetti, who, as head of the Fraud Detection and National Security (FDNS) unit, oversaw preparation of the asylum fraud report cited by the Washington Times, testified that the report — unlike many others his unit prepared — never received agency leadership approval for finalization or publication, despite his belief that it should have.32

As noted by Center for Immigration Studies Director of Policy Studies Jessica Vaughan, “Crocetti [also] stated that USCIS has devoted little attention to fraud in the last few years and no longer conducts audits to determine fraud rates in any categories.”33 Those of a cynical disposition might be inclined to believe that the agency does not wish to explore the depth of fraud across the range of its benefits-granting programs, including asylum, lest its inordinately high approval rates be placed under a microscope.

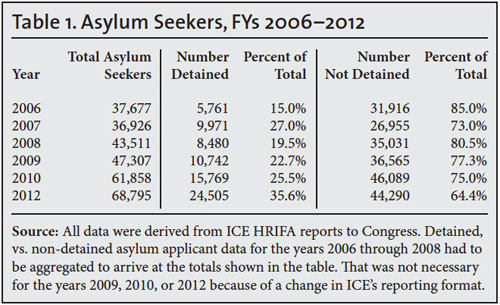

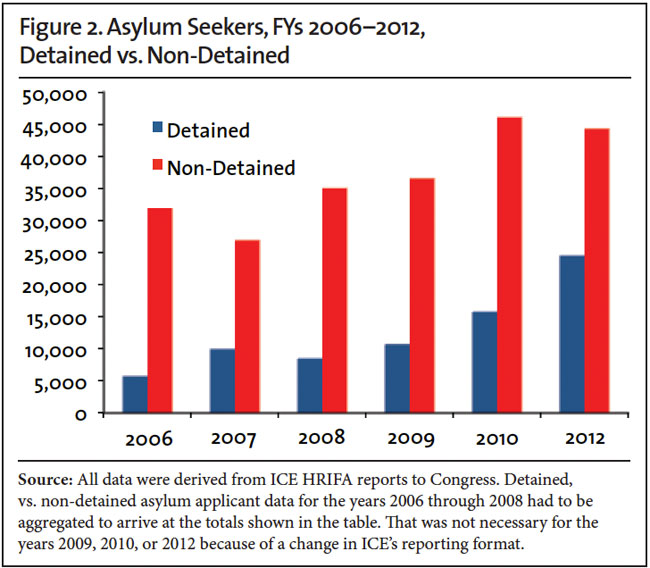

Detention as a Deterrent. Detention of asylum seekers as a deterrent to false or frivolous claims is only as viable as its responsible use. Congressional interest in the fair but effective use of detention has been underscored by a provision of the Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act of 1998 (HRIFA), which requires yearly reporting by ICE of statistical data relating to those aliens who have been detained after making a claim to asylum.34 It is important to note, however, that many aliens who are initially detained pending a credible fear determination are released as soon as an asylum officer finds that the alien has met that threshold. Thus, when nearly every fear is deemed credible, the credibility of detention itself as a preventive to fraud and abuse plummets.

But what if there is no detention of an asylum-seeking alien? In December 2009, then-ICE Director John Morton promulgated a national policy stating that, effective January 4, 2010, detention of intended asylum seekers would no longer form a part of the agency’s detention priorities.35

This national policy — which was issued by Morton without abiding by the procedures laid out in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), thus violating that law36 — also violates the INA, which states “If the officer determines at the time of the interview that an alien has a credible fear of persecution … the alien shall be detained for further consideration of the application for asylum.”37 (Emphasis added.)

Yet an examination of prior ICE reports submitted pursuant to HRIFA reveals that the de facto policy existed prior to Morton’s directive. Table 1 shows the number of detained vs. non-detained asylum seekers for federal fiscal years 2006 through 2012, the most recently issued. Readers will note that the data from FY 2011 are missing. This is because, despite the statutory mandate, it appears that there have been years in which ICE has not complied, one of them being 2011.

Readers will readily see in Figure 2 that the number of asylum applicants who are not detained far outweighs those who are detained.

If detention no longer forms a part of the DHS strategy to control abusive asylum claims, then it must follow that aliens will have no fear of detention as a preventative against making fraudulent assertions. And it is clear that has been the case for several years.

Hipolito Acosta, a highly decorated retired DHS official with significant experience in both the immigration law enforcement and benefits adjudication arenas, testified at a second House of Representatives hearing on asylum, on February 11, that:

[T]he ability to make a claim, whether genuine or not, that results in release and being able to continue travel into the United States to rejoin family members and in most cases, never report for any immigration hearings scheduled has been the magnet for those seeking entry into the United States.38

ICE, the DHS agency charged with ensuring the integrity of the asylum system through legally mandated detention, has compromised that integrity through policies that actively discourage the detention of the majority of asylum seekers, and open the doors wide to abuse through fraud and frivolous claims.

The significance of ICE’s detention failure cannot be overstated. In a May 2011 CIS Backgrounder, former immigration judge Mark Metcalf noted that:

- “Aliens [including failed asylum seekers who have not been detained] evade immigration courts more often than accused felons evade state courts. Unlike accused felons, aliens who skip court are rarely caught.”

- “From 1996 through 2009, the United States allowed 1.9 million aliens to remain free before trial and 770,000 of them — 40 percent of the total — vanished. Nearly one million deportation orders were issued to this group — 78 percent of these orders were handed down for court evasion.”

- “From 2002 through 2006 — in the shadow of 9/11 — 50 percent of all aliens free pending trial disappeared. Court numbers show 360,199 aliens out of 713,974 dodged court.”39 (Emphasis added.)

Decoupling Asylum Claims from Immediate Work Authorization. Once an alien is released from detention (if indeed he is ever detained), he must of course wait the required period (150 days) while his actual asylum application is pending before seeking an Employment Authorization Document (and a further 30 days before receiving work authorization). But the reality is, of course, far different: there is a vast underground of employers in this country who are willing to employ aliens without work authorization — that number increases dramatically if the employer can be persuaded that it is as simple as waiting six months until the alien will be able to present proof of work authorization. And so the withholding of work authorization as a deterrent to fraud and abuse is also an empty threat.

As can be seen, credible fear determinations are the thread holding the entire fabric of asylum checks and balances together. Failing that thread, the fabric falls apart. As noted by Rep. Goodlatte in his opening statement during the House hearing in December, “Currently, data provided by DHS show that USCIS makes positive credible fear findings in 92 percent of all cases decided on the merits. Not surprisingly, credible fear claims have increased 586 percent from 2007 to 2013 as word has gotten out as to the virtual rubberstamping of applications.”

But there are other significant problems in addition to outright fraud that have to do with the continually expanding universe of bases on which to file a claim of asylum.

A Plethora of Protections

Over the course of time, some of the interpretations of “covered grounds” that have become accepted, indeed precedential, are not at all evident from the plain language of the statute. Many of these revolve around expanding notions of what constitutes a particular social group or a political opinion:40

- The right to have as many children as one wishes: Foreign government policies requiring abortions and sterilization afford a basis to seek asylum in the United States; this was in direct reaction to the “one child” rule of the Chinese Communist Party, which regulated it in the People’s Republic by forced abortions (even in the third trimester) when necessary.41

- Female genital mutilation: Women in societies that, for cultural or religious reasons, alter female genitalia without the women’s permission, are entitled to claim asylum.

- Homosexual or transgender orientation: People whose sexuality subjects them to condemnation, imprisonment, or abuse in their society may claim protection through asylum.

- Imputed political opinion: Individuals who possess no strong political opinions — but who have a political opinion imputed to them that results in their persecution by a government, or by rebel groups from whom the government cannot protect them, may claim protection through asylum.

The above examples reflect just a few of the interpretations that have become the norm. It is easy to see the logic at work in these interpretations; it is also easy to see how they might be abused by persons whose sole intention is to immigrate, but who might otherwise be unable to do so for lack of the skills or family ties required under our visa system. And indeed, they have been.

It is often difficult for officers who adjudicate such claims to adequately and independently verify the claims made, and to make informed credibility determinations regarding an individual’s representations. That is why this important work should be free from outside influence or politicization of any kind. Unfortunately, DHS and USCIS leaders in the present administration have exercised a heavy hand and done everything possible to discourage denials, or to overturn them and insist on approvals across a broad spectrum of adjudications.42 This is unacceptable in any form of immigration benefit, let alone with one so sensitive as asylum.

Some of the expanded interpretations of protected individuals that have come into being over time simply reflect emerging attitudes and American social consensus. Others of a more recent nature, such as the troublesome new administration “notice of determination” watering down the bars to granting asylum or refuge to terrorists, beggar belief and form the basis for some of the outrage being expressed today.

The legal precedents permitting grant of asylum to individuals for imputed political opinions also hold a significant potential for trouble. As wars rage throughout the world, many of them of an internal nature such as those in Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s, it is a foregone conclusion that large segments of those societies will get caught in the middle, wanting little or nothing to do with either side, but victimized by both insurgents and government, each equally pitiless and brutal. That is the case in Syria right now. But are we prepared to accept whole swaths of foreign populations from each trouble spot on the globe as an antidote to our troubled consciences and our understandably increasing unwillingness to put boots on the ground and intervene?

Finally, and most troubling, even as the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the administrative appellate tribunal with jurisdiction over appeals from decisions of the immigration courts, has tried to hold the line on interpretations of protected classes from being extended to former gang members, it has been overruled by some of the federal circuit courts, most notably the Sixth, Seventh, and, most recently, Eighth and Fourth Circuit Courts of Appeal.

Eighth Circuit Case: Gathungu v. Holder.43 In a decision last August, the Eighth Circuit held that a man who had “defected” from the Mungiki criminal gang of Kenya constituted part of a “particular social group”, and was therefore entitled to protection under the asylum laws. The man, Kenyan businessman Francis Gathungu, testified that he had unwittingly joined the group. This is difficult to credit given the infamy of Mungiki in Kenyan society and the flagrant openness with which it operates. What is more, “Mungiki followers no longer sniff tobacco in public and have traded in their dreadlocks and unkempt appearance for neat haircuts and business suits.”44 It is signal that Mr. Gathungu described himself in his application and testimony as a “Kenyan businessman”.

Lending further doubt to Mr. Gathungu’s story is that it parallels in some ways other accounts of “former” Mungiki members that have proven fraudulent in the United Kingdom.45 What is more, fabricated accounts are not uncommon and are difficult to detect, as was noted by professor Jan Ting in his testimony for the record before the House of Representatives in its most recent hearing on the U.S. asylum program.46

It is important to note that the circuit courts do not hear testimony; their decisions are made from the written record. In this case, the Eighth Circuit overruled the findings of both the initial trier of fact, an immigration judge who was present when Gathungu testified and was well-poised to make credibility judgments, and the BIA, which had also denied his request for asylum at the administrative appellate level.

Fourth Circuit Case: Martinez v. Holder.47 Although in this case the protected class was extended to withholding of removal and not asylum, the key point is that the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals has now found that being a “former” member of a criminal gang — the particularly violent MS-13 — is to be a member of a “particular social class” and therefore entitled to protection. One can readily extrapolate from this finding that it is only a matter of time until the premise is applied to asylum as well.

There is something decidedly wrong, almost perverse, about according the privilege of asylum, or even withholding of removal, to persons who have participated in criminal organizations, whether or not they have themselves been caught at, and convicted of, particularly serious offenses. These are individuals who have by their own admission supported organizations whose violence against others is horrific, well-documented, systematic, and widespread. Does it simply take a “mea culpa” to absolve them of responsibility or accountability for that support, no matter what form it took? After all, support of such organizations cannot in any form be benign. Is their victimization of others in pursuit of the gang’s goals not adequate to constitute a bar to relief? Has personal responsibility for crimes committed by organizations not been one of the most important lessons of the past 60 or 70 years of mankind’s history?

We live in a world of asymmetrical threats, where dangerous organizations cannot neatly or accurately be pigeonholed into one category or another. For example:

- The Taliban, a terrorist organization, actively promotes the cultivation of poppies and production of heroin in Afghanistan.

- The insurgent group FARC in Colombia did the same before them, primarily with cocaine and secondarily with marijuana; it was from the FARC’s activities that the phrase “narco-terrorism” was born.

- Mexican cartels exist to make massive profits from narcotics, but use weapons and alien smuggling as tools to further their aims; and they do not hesitate to use murder and terror to paralyze the population and impede the Mexican state in its efforts to stamp them out.

- Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), a U.S. Treasury-designated “transnational criminal organization” operating in the United States and Central America, routinely uses violence and the threat of violence toward other gangs; toward potential witnesses against them, real or potential; and toward innocent members of the community to intimidate them into silence. MS-13 is even brutal to its own, as evidenced by the “beat-downs” and gang rapes practiced in its gang initiation rites for males and females, respectively.48 In some Central American countries such as El Salvador, the gang is so powerful that it is a destabilizing influence on the functions of government and society.

- Hizballah, a fundamentalist Shi’a group with strong Iranian backing, as well as a designated terrorist organization, actively engages in a wide variety of narcotics and contraband smuggling, among other criminal activities throughout the world (including North and South America) in order to finance its military operations in Lebanon, Syria, and elsewhere.

- The Lord’s Resistance Army, which operates mostly (but not exclusively) in Uganda is part cult, part criminal organization, part insurgency, part terrorist group, and all evil.

- The same is true of the Mungiki, lately of Eighth Circuit notoriety.49

In a recent article published in National Review, professors Robert Delahunty and John Yoo brought to light another deeply troubling case: that of Ali Mohamed Ali, suspected Somali pirate, captured by the U.S. Navy and brought to the United States to be tried for his crimes.50 A jury, for reasons one can only speculate about, declined to convict Ali on some charges and federal prosecutors (again, for reasons one can only speculate about) then dropped all other charges. As the professors pointedly observe, Ali — now being physically in the United States — is entitled to apply for asylum. There is little doubt that, aided by his attorneys, he is doing so. But even assuming that his application fails, will USCIS adjudicators or immigration judges then grant him protection under removal-of-withholding or CAT provisions? Such a result is beyond ironic.

When executive action waters down terrorist bars and judicial activism interprets asylum law to permit “reformed” gang members and international pirates to reside legally in the United States, something has gone seriously awry. Why is our generous nation so determined to grant asylum and other protections to individuals who have actively supported the victimization of others through membership or participation in the terrorist organizations-cum-gangs-cum-rebel groups-cum-pirate bands they have belonged to? This is a kind of moral relativism difficult to comprehend, let alone justify.

Conclusion

The difficulties facing the asylum program are not only qualitative, but quantitative and the two are inextricably linked. As legal interpretations of protected classes and political opinions expand; and as adjudicators and immigration judges deny fewer and fewer cases, and as at least selected circuit courts exercise judicial activism to inappropriately expand the interpretations of protected classes, more and more individuals seek to avail themselves of the benefits of asylum, whether merited or not. After all, what have they to lose? Nothing at all.

Such an atmosphere fosters fraud, and the danger with rampant fraud in such a sensitive program is that it ultimately engenders “compassion fatigue” among Americans who become fed up with alien asylum applicants, many of whom are gaming the system, and some of whom are much, much more sinister than simply liars and con artists. In the long run, this puts legitimate asylum seekers at risk.

The Gang of Eight Bill Would Further Undermine Controls

Curiously, despite the clear existence of many danger signs warning that the nation’s asylum program is seriously malfunctioning, the omnibus “Gang of Eight” immigration bill passed by the Senate51 would do nothing to curb the abuses and put the program on a correction course that better meets the needs of public safety and national security. Instead, the bill contains provisions that obviate even the most fundamental checks and balances in a well-functioning system:

Section 2101(a) of the bill would:

- Forgive aliens seeking amnesty who previously filed frivolous asylum claims; and

- Prohibit the detention of aliens apprehended (even in close proximity to the border) if they make a claim to eligibility for amnesty no matter how frivolous and even if they were previously deported after having made an unsuccessful claim to asylum.

Section 3104 of the bill would:

- Eliminate the statutory requirement that asylum claims be filed within one year of arrival;

- Permit aliens previously denied asylum to seek reopening of their cases, if the denial was due to failure to apply within the year or if they were granted withholding of removal in lieu of asylum; and

- Permit aliens to seek reopening of prior asylum denials based on the ambiguous phrase “changed circumstances”.

Section 3404 of the bill would:

- Eliminate the provision in the INA requiring detention of arriving aliens who apply for asylum;

- Require that “non-adversarial” interviews be conducted at the time of arrival, no matter how spurious the claim might appear, and what grounds of inadmissibility apply; and

- Oblige asylum officers, after obtaining supervisory approval, to grant asylum on the spot when they determine it appropriate.

This latter provision of the Senate bill is disturbingly ill-advised:

- While it is true that DHS and its components have embarked on a mistaken policy of turning their backs on the statutory detention requirement (with obvious adverse consequences as evidenced by the statistics and case-specific evidence), eliminating the statute is even more mistaken.

- It is a mistake to conflate interviewing objectives when confronting aliens who have just arrived in order to get to the truth. Sometimes such interviews take on the aspect of interrogations in secondary inspections, and rightly so. This is in the interest of the American public, which has the right to expect its port of entry (POE) inspectors to protect the nation and safeguard the integrity of our borders.

- It is unreasonable to expect asylum officers to make intelligent, informed judgments about the propriety of a claim, or the truthfulness and accuracy of assertions made by applicants, in the environment of a POE or immediately after arrival. How does the asylum officer avail himself of adequate information about country conditions and other data, which are often voluminous and detailed, that may be relevant to the claim?

- Spontaneous grants at POEs, based on non-confrontational interviews, permit no opportunity to thoroughly vet the individual and ensure that he is not a persecutor, war criminal, terrorist, or otherwise undesirable and ineligible for asylum. When exactly do the requisite background checks take place in such a milieu?

It seems obvious that the hole into which the asylum program has climbed, in no small measure because of the inapt, and sometimes inept, decisions of all three branches of government established by the Constitution will not be well served by going in the direction the Senate bill would drive it. What should be done instead?

Recommendations

First and foremost, the House of Representatives, in its deliberations over immigration reform measures, must reject all of the asylum-related provisions contained in the Gang of Eight bill. They are singularly out of touch with the realities of the problem-plagued asylum program.

Congress must take steps to legislatively curb the propensity of courts to grant protections to aliens who are members of, have participated in, or have materially supported heinous criminal organizations or insurgencies — whether they are transnational or indigenous to a particular region — if those organizations systematically victimize others. This can be done by amending current language that limits the persecutor bar only to those who persecute under the five designated grounds, or by adding supplementary language to establish victimization of others with the purpose of furthering unlawful objectives as a bar to asylum or refuge.

Congress must roll back the recently-issued “Notice of Determination” promulgated by the administration with relation to terrorism and material support waivers.

DHS (and, failing its action, Congress) must immediately institute a mandatory program of routine audits of a percentage of both credible fear findings, and formal asylum grants — perhaps an across-the-board 10 percent of all cases — as a method of detecting fraud and ensuring appropriate findings of credibility, and approval of asylum cases. For quality control and integrity reasons, the audit program should include both pre-decisional cases that are on the cusp of being issued and post-decisional cases as well. For each case in which fraud or withholding of material information is found, USCIS should refer, and ICE accept for investigation, the case.

The Justice Department, via the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys, should issue instructions to each U.S. Attorney’s Office that prosecution of asylum (or refugee) fraud and misrepresentations constitutes a priority.

Congress should amend the INA to provide that refugees and asylees will only be entitled to apply for conditional residence after a year in status, and not eligible to apply for adjustment to full lawful permanent resident status until after three years. This regimen is consistent with current law and procedures relating to aliens who derive benefits from marriage to a U.S. citizen — another program that has been plagued with fraud in the past. Although the three years of conditional residence does not eliminate fraud, it acts as a levee against an overwhelming volume of fraud while at the same time permitting government officials additional opportunities to further examine the bona fides of cases before immediately granting resident alien status.

Each application for adjustment of status filed by an asylee or refugee should, prior to adjudication, include careful consideration of whether there are changed conditions that merit denial of adjustment and termination of asylee or refugee status. This consideration also affords the government a chance to initiate a second look at whether the initial grant was appropriate or, as in the case of Jorge Sosa-Orantes, a Guatemalan war criminal, facts can be brought to light showing that the individual should be placed instead into removal proceedings.52

Congress should amend the INA to provide that return to the ostensible country of persecution, however briefly, by a refugee or asylee at any time prior to adjustment to full lawful permanent residence shall be deemed prima facie evidence that the individual is not entitled to such status, and require him to be placed into removal proceedings.

Finally, ICE must renew its commitment to effective use of detention of arriving asylum seekers, consistent with its statutory mandate.

End Notes

1 Brian Bennett, “Immigration claims for asylum soar”, The Los Angeles Times, December 12, 2013.

2 “Asylum Abuse: Is It Overwhelming Our Borders?”, House Judiciary Committee, testimony of Ruth Ellen Wasem, specialist in immigration policy, Congressional Research Service, December 12, 2013.

3 “Temporary asylum” means a finding by an asylum officer that an alien has expressed a credible fear of persecution if returned to his country — a finding that triggers a near-automatic grant of asylum after the individual is interviewed subsequent to filing his or her formal application. This permits the individual to lawfully remain in the United States for many months, sometimes years due to backlogs, and obtain an employment authorization document (after a short hiatus of 180 days during which work permits are barred) while awaiting the interview.

4 “Asylum Abuse: Is It Overwhelming Our Borders?”, House Judiciary Committee, opening statement of Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), chairman of the committee, December 12, 2013.

5 Another form of non-return under the INA is Temporary Protected Status (TPS); it has not been placed within the list in the body of this paper because TPS is granted as the result of extraordinary conditions not recognized by international law as legally obligating non-refoulement — conditions often attributable to hurricanes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, but also sometimes due to war and civil strife (thus making the distinction from non-refoulement murky). What is more, despite use of the word “temporary”, TPS has been granted in regulatory increments to nationals of some nations for many years.

6 A copy of the Convention in its entirety may be found at the U.S. State Department’s website.

7 8 U.S.C. § 1157, although the word “refugee” is defined at 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42).

8 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Refugees and Asylum”.

9 For more on refugees generally, or the Lautenberg and Specter amendments in particular, see Andorra Bruno’s August 8, 2013, Congressional Research Service report, “Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy”.

10 8 U.S.C. § 1158.

11 The sole procedure for applying to adjust status based on a grant of asylum can be found at 8 CFR § 1209.2. USCIS has developed a number of aids to assist asylees in this process. See, for instance, Pamphlet D3 (English), “I am a refugee or asylee: How do I become a U.S. permanent resident?”.

13 Such assurances, when proffered by a country, are carefully examined by officials from both the departments of State and Homeland Security and, before being accepted, are sometimes accompanied by the stipulation that American consular or other officials must be provided periodic access to the individual to ensure that the country abides by its commitment.

14 For a more detailed explanation of withholding of deportation, and relief under the Torture Convention, see “Pro Bono Asylum Representation Manual, Section III: Alternatives To Asylum” on the Advocates for Human Rights website.

15 There is more than a little irony in their opposition to structured repatriation under such circumstances since the self-same human rights groups are also extremely vocal when the U.S. government appears to have given safe haven to tyrants, war criminals, or other egregious human rights abusers.

16 United States Supreme Court, Zadvydas v. Davis, (99—7791 and 00—38), 185 F.3d 279 and 208 F.3d 815, decided June 28, 2001.

17 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website, op. cit.

18 Even as this paper was being written, the BIA issued two new precedents, in Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 208 and Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227 (both decided February 7, 2014), concerning the doctrine of “social visibility” as a requisite element of establishing the existence of a particular social group.

19 A detailed exposition of refugee law and policy is outside the scope of this paper, but such a document has been prepared by Andorra Bruno for the Congressional Research Service: “Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy”, August 8, 2013.

20 One instance in the context of defensive asylum claims in which an immigration judge does not preside over inadmissibility or deportation charges in tandem with an asylum claim, is when the alien is subject to expedited removal under the law. In that instance, the judge will only hear the claim relating to asylum; if it fails, the alien will be removed under expedited procedures that do not require an immigration court hearing.

21 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Obtaining Asylum in the United States”.

22 “Real ID Act Long Form Boilerplate Language”, IJ Benchbook, U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review.

23 INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987).

24 For particular examples of fraud and coaching, see Sam Dolnick, “Immigrants May Be Fed False Stories to Bolster Asylum Pleas”, The New York Times, July 11, 2011; and “Twenty-Six Individuals, Including Six Lawyers, Charged In Manhattan Federal Court With Participating In Immigration Fraud Schemes Involving Hundreds Of Fraudulent Asylum Applications”, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, press release, December 18, 2012.

25 Individual country reports can be found on the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights website; and at the U.S. State Department’s website.

26 For more detailed information concerning the notice and its potential harm to public safety and national security, see the author’s blog, “Government by Fiat: Granting Discretionary Waivers for Terrorism Supporters”, Center for Immigration Studies, February 7, 2014.

27 “Asylum Trends 2012: Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries”, UNHCR, March, 2013.

28 See Deborah J. Saunders, “When Fraud Pays, Time Has Come For Overhaul Of U.S. Immigration Policy”, Ft. Lauderdale Sun Sentinel, March 30, 1993.

29 To see how the exception is applied by asylum officers, see the “Asylum Officer Basic Training Participant Workbook: One Year Filing Deadline Lesson”, p. 8.

30 A complete exposition, from the private practitioner’s point of view, of the one-year filing rule and application of the “changed circumstances” exception can be found at the Immigration Equality website: “5. Immigration Basics: The One-Year Filing Deadline”.

31 Stephen Dinan, “Audit finds asylum system rife with fraud; approval laws broken with surge of immigrants”, the Washington Times, February 5, 2013.

32 “Asylum Fraud: Abusing America’s Compassion?”, House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, testimony of Louis D. Crocetti, former associate director, U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services, February 11, 2014.

33 Jessica Vaughan, “House Hearing on Asylum Reveals Rampant Fraud, More Abuse of Executive Discretion”, Center for Immigration Studies blog, February 11, 2014.

34 HRIFA Section 903, which is found in Title IX of Pub. L. 105-277, Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations, 112 Stat. 2681 (codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1377), requires the following:

SEC. 903. COLLECTION OF DATA ON DETAINED ASYLUM SEEKERS.

(a) IN GENERAL. — The Attorney General shall regularly collect data on a nation-wide basis with respect to asylum seekers in detention in the United States, including the following information:

(1) The number of detainees.

(2) An identification of the countries of origin of the detainees.

(3) The percentage of each gender within the total number of detainees.

(4) The number of detainees listed by each year of age of the detainees.

(5) The location of each detainee by detention facility.

(6) With respect to each facility where detainees are held, whether the facility is also used to detain criminals and whether any of the detainees are held in the same cells as criminals.

(7) The number and frequency of the transfers of detainees between detention facilities.

(8) The average length of detention and the number of detainees by category of the length of detention.

(9) The rate of release from detention of detainees for each district of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

(10) A description of the disposition of cases. “

(b) ANNUAL REPORTS. — Beginning October 1, 1999, and not later than October 1 of each year thereafter, the Attorney General shall submit to the Committee on the Judiciary of each House of Congress a report setting forth the data collected under subsection (a) for the fiscal year ending September 30 of that year.

(c) AVAILABILITY TO PUBLIC. — Copies of the data collected under subsection (a) shall be made available to members of the public upon request pursuant to such regulations as the Attorney General shall prescribe.

35 “ICE issues new procedures for asylum seekers as part of ongoing detention reform initiatives”, news release, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, December 16, 2009.

36 The APA is codified at Title 5 of the United States Code, Subchapter II. 5 U.S.C. § 551 states in pertinent part, “(a)(1) Each agency shall separately state and currently publish in the Federal Register for the guidance of the public … (D) substantive rules of general applicability adopted as authorized by law, and statements of general policy or interpretations of general applicability formulated and adopted by the agency.” (Emphasis added.) The APA also requires federal agencies to promulgate such statements of general policy in the Federal Register sufficiently in advance to permit interested persons and groups to comment upon them, so that the agency may review the comments and take corrective actions based on the commentary prior to finalizing such policies.

37 INA Section 235(b)(1)(B)(ii), codified as 8 U.S.C. § 1225 (b)(1)(B)(ii).

38 “Asylum Fraud: Abusing America’s Compassion?”, House Judiciary Committee, testimony of Hipolito Acosta, former district director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, February 11, 2014.

39 Mark Metcalf, “Built to Fail: Deception and Disorder in America’s Immigration Courts”, Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, May 2011.

40 For one discussion of the evolving thought regarding what constitutes a “particular social group”, see “Gender-Related Asylum Claims and the Social Group Calculus: Recognizing Women as a ‘Particular Social Group’ Per Se”, a report by the New York City Bar Association’s Committee on Immigration and Nationality Law, March 27, 2003.

41 Congress felt so strongly about enforced abortions and sterilizations that it also amended the law to prohibit the entry of any individuals “engaged in establishment or enforcement of forced abortion or sterilization policy”. See, 8 U.S.C. § 1182E.

42 See David North, “DHS Inspector-General Writes a Stunning Report on USCIS”, Center for Immigration Studies blog, January 11, 2012.

43 Gathungu, et al, v. Holder, United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, No. 12-2489, decided August 6, 2013.

44 BBC News, “Profile: Kenya’s secretive Mungiki sect”, May 24, 2007.

45 See John Ngugi, “Confessions of a Mungiki man and tall tales asylum seekers tell”, in the London Diary at the online Digital Standard News, accessed February 13, 2014.

46 “Asylum Fraud: Abusing America’s Compassion?”, House Judiciary Committee, testimony of Jan C. Ting, professor of law, Temple University Beasley School of Law, February 11, 2014.

47 Martinez v. Holder, United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, No. 12-2424, decided January 23, 2014, revised January 27, 2014.

48 Such initiation rites seem to be practiced almost across the board, not just by MS-13, but by many other gangs in the United States and elsewhere. For examples of gang initiation rites, see The Daily Motion, “A Video (without Audio) Shows a Gang Initiation Ritual Involving a Regina Teen”, undated; The History Channel online, “Gangland: Gang Initiation Rituals”, accessed February 13, 2014; Rob Cooper, The Daily Mail Online, “Victim of a horrifying ‘gang initiation’: This young woman was clawed in the face by a female attacker as she walked in the park”, June 15, 2012; and Mark Townsend, “Being raped by a gang is normal – it’s about craving to be accepted”, The Guardian, February 18, 2012.

49 See, for instance, “Mungiki-Topic: Popular Mungiki Videos” on YouTube.

50 Robert Delahunty and John Yoo, National Review Online, “Only under Holder: A suspected pirate, freed after a civilian trial, is seeking asylum here”, February 18, 2014.

51 Officially known as the “Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act” (S.744), which passed the full Senate in June 2013.

52 See the author’s blog, “Sheltering Abusers”, Center for Immigration Studies, February 12, 2014.

Comments are closed.