AVI SHAVIT’S LIES AND LIBEL ****

http://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/2014/07/what-happened-at-lydda/?mode=print

In his celebrated new book, Ari Shavit claims that “Zionism” committed a massacre in July 1948. Can the claim withstand scrutiny? By Martin Kramer

“In 30 minutes, at high noon, more than 200 civilians are killed. Zionism carries out a massacre in the city of Lydda.”— Ari Shavit, My Promised Land

Perhaps no book by an Israeli has ever been promoted as massively in America as My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, by the Ha’aretz columnist and editorial-board member Ari Shavit. The pre-publication blitz began in May 2013, when the author received the first-ever Natan Fund book award, which included an earmark of $35,000 to promote and publicize the book. The prize committee was co-chaired by the columnist Jeffrey Goldberg and Franklin Foer, editor of the New Republic; among its members was the New York Times columnist David Brooks. Not only was the choice of Shavit “unanimous and enthusiastic,” but Goldberg and Foer also supplied florid blurbs for the book jacket. Goldberg: “a beautiful, mesmerizing, morally serious, and vexing book,” for which “I’ve been waiting most of my adult life.” Foer: “epic history . . . beautifully written, dramatically rendered, full of moral complexity . . . mind-blowing, trustworthy insights.”

Upon publication last November, the book proceeded to receive no fewer than three glowing encomia in the Times from the columnist Thomas Friedman (“must-read”), the paper’s literary critic Dwight Garner (“reads like a love story and thriller at once”), and the New Republic‘s literary editor Leon Wieseltier (“important and powerful . . . the least tendentious book about Israel I have ever read”). From there it jumped to the Times’s “100 Notable Books of 2013” and to the non-fiction bestseller list, where it spent a total of six weeks.

The Times was hardly alone. The editor of the New Yorker, David Remnick, who is credited by Shavit with inspiring the book and curating its journey into print, hosted a launch party at his home and appeared with Shavit in promotional events at New York’s 92nd Street Y, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, and the Charlie Rose Show. Jeffrey Goldberg likewise surfaced alongside Shavit both on Charlie Rose and at campus whistle stops.

“What happened during the first week of my book’s publication went beyond anyone’s expectation, beyond my dreams,” marveled Shavit in an interview. In January, he collected a National Jewish Book Award. In short order, he became a must-have speaker for national Jewish organizations from AIPAC to Hadassah, and a feted guest at the Beverly Hills homes of media mogul Haim Saban and the producer-director Tony Krantz. “If you want to see what prophecy looks like among Jews in the early part of the 21st century,” wrote an attendee at one of these soirées, “follow Ari Shavit around Los Angeles.”

Beyond Shavit’s powerful writing style and engaging personal manner, what inspired this outpouring? “My book,” he says, “is a painful love story,” the love in question being his professed “total commitment to Israel, and my admiration for the Zionist project,” tempered by his conspicuously agonized conscience over the misdeeds of that state and that project. It was, undoubtedly, this dual theme that gave the book its poignant appeal to many American Jewish readers eager to revive a passion for Israel at a time when Israel is defined by much of liberal opinion as an “occupier.” To achieve his artfully mixed effect, Shavit adopted a particular strategy: confessing Israel’s sins in order to demonstrate the tragic profundity of his love.

And the sins in question? The obvious one in the book is the sin of post-1967 “occupation.” But many readers were especially taken aback to learn of an earlier and even more hauntingly painful sin. This one, detailed in a 30-page chapter titled “Lydda, 1948,” concerns an alleged massacre of Palestinian Arabs that preceded an act of forcible expulsion. Shavit’s revelation: Lydda is “our black box.” In its story lies the dark secret not only of the birth of Israel but indeed of the entire Jewish national movement—of Zionism.

The Lydda chapter gained resonance early on because Shavit’s friends at the New Yorker decided to abridge and publish it in the magazine. There, it ran under an expanded title: “Lydda, 1948: A City, a Massacre, and the Middle East Today.” The meaningful addition is obviously the word “massacre.” An informed reader might have heard of another 1948 “massacre,” the one in April at the Arab village of Deir Yassin. But at Lydda? Who did it? Under what circumstances? How many died? Was it covered up?

“Massacre” is Shavit’s chosen word, but he doesn’t define it. Instead, he proposes a narrative of the events that occurred around midday on July 12, 1948, in the midst of Israel’s war of independence, when Israeli soldiers in Lydda faced an incipient uprising. This narrative he claims to have constructed from interviews he conducted twenty years ago, “in the early 1990s.” He spoke then with Shmarya Gutman, the Israeli military governor of Lydda who negotiated the departure of its Arab inhabitants; the commander (his name was Mula Cohen) of the Yiftah brigade, which quelled the uprising; and someone identified only by his nickname, “Bulldozer,” who fired an antitank shell into a small mosque, supposedly killing 70 persons at one blow. Shavit’s dramatic culmination comes in the assertion that leads this article: “In 30 minutes, at high noon, more than 200 civilians are killed. Zionism carries out a massacre in the city of Lydda.”

So explosive is this claim that Shavit seems to have realized it could play into the hands of those eager to delegitimate Israel’s very existence. “I really take issue with people who pick out Lydda and ignore the rest of the book,” he has lamented (a complaint perhaps best directed to the New Yorker). In interviews and appearances over the past months, he has gone farther, insisting that Israel’s deeds in Lydda must be seen in the context of a brutal war in a brutal decade; that the Arabs would have done worse to the Jews; and that Western democracies did do worse to their own “Others,” from Native Americans to Aboriginal Australians, so who are they to preach moral rectitude to Israel?

This sort of damage control, whatever its short-term effect, is unlikely to negate the one probable long-term impact of Shavit’s book: its validation of the charge of a massacre at Lydda, carried out by Zionism itself and thereby epitomizing the ongoing historical scandal that is the state of Israel.

So whether Shavit “takes issue” or not, his narrative of Lydda invites an inevitable question: is it true?

Others have found Shavit’s account of Lydda “riveting” (Avi Shlaim), “a sickening tour de force” (Leon Wieseltier), and “brutally honest” (Thomas Friedman). As I read through it, however, the alleged actions and attitudes of Shavit’s Israeli protagonists struck me as implausible. To me they seemed to personify much too readily Shavit’s broader thesis: that “Zionism” had been preprogrammed to depopulate the country of its Arabs, and that this preprogramming filtered down even to the last soldier. In Lydda, soldiers licensed by “Zionism” then became wanton killers of innocents, smoothing the work of expulsion.

Perhaps my suspicion was stoked by the fact that, time and again over the decades, Israeli soldiers have stood accused of just such wanton killing when in fact they were doing what every soldier is trained to do: fire on an armed enemy, especially when that enemy is firing at him. That such accusations might even be accompanied by professions of “love” for Israel is likewise no novelty. (See under: Richard Goldstone.) When such charges are made today, they tend to be subjected to rigorous investigation. Could Shavit’s narrative withstand a comparable level of scrutiny?

Shavit relies largely on his interviews, conducted those many years ago. Since he doesn’t cite documents in a public archive, I have no way of knowing whether he fairly represents his subjects. But it did occur to me that these same protagonists may have told their stories to others. And, with a bit of research, I discovered that they had.

Shmarya Gutman, Mula Cohen, “Bulldozer,” and others who fought in Lydda in July 1948 not only were interviewed by others but were even interviewed on film at the very places where they had fought. The evidence reposes in the archives of the museum of the Palmah (the Haganah’s strike force) in Ramat Aviv, where I found it and where it may be consulted by anyone. (I’m indebted to Dr. Eldad Harouvi, director of the archives, who expertly guided me through the collection.) Especially valuable is the uncut footage filmed by Uri Goldstein in preparing a 1989 documentary on the Yiftah brigade: the Israeli army unit, comprising fighters from the pre-state Palmah, that conquered Lydda. The same museum also holds transcripts of relevant interviews archived in the Yigal Allon Museum at Kibbutz Ginosar.

Some of the testimony in the archives echoes the account given by Shavit. But there are major inconsistencies; not only are these numerous, but they form a pattern. In what follows, I invite you, the reader, to detect that pattern on your own. Remember that the evidence derives largely from testimony given by the same people whom Shavit interviewed only a few years later. I have supplemented it with additional oral testimony by Israeli soldiers whom Shavit should have interviewed, if he had wanted to be thorough.

A caution: “Zionism carries out a massacre” is a lapel-grabbing phrase, meant to excite and provoke. In comparing accounts of a battle, however, sober details make all the difference. As it happens, many of Shavit’s readers have praised his book for adding complexity to Israel’s story, thus replacing old “myths” with a more nuanced understanding. Shavit himself has proclaimed that Israel is “all about complexity. If you don’t see that, you don’t get it.” For anyone with a taste for complexity, what follows should constitute indispensable reading alongside the rather simpler tale entitled “Lydda, 1948.”

1. Lydda, July 11-13, 1948

First, recall the overarching framework. By the summer of 1948, Israel’s war of independence had entered a new phase. Now Israel battled not only local Arab irregulars but also Arab armies, first and foremost the Transjordanian Arab Legion, deployed in Jerusalem and just east of Jewish towns and settlements on the coastal plain. On July 4, 1948, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion approved a military plan called “Larlar,” an acronym for Lydda-Ramleh-Latrun-Ramallah. The operation was meant to open a broad corridor to Jerusalem, which was in danger of being severed from the Jewish state.

Lydda, along the route from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, was an Arab city of some 20,000, swollen by July to about twice that size by an influx of refugees from Jaffa and neighboring villages already occupied by Israeli forces. The 5th Infantry Company of the Transjordanian Arab Legion (approximately 125 soldiers) was deployed in the city, supported by many more local irregulars who had been making months-long preparations for battle.

On July 11, Israeli troops under the command of Moshe Dayan put Lydda (and Ramleh) in a state of shock with a guns-ablaze dash skirting both towns. But the city was not yet subdued. That evening, the 3rd Battalion of the Yiftah brigade moved into southern approaches to the city, took the two landmarks of the Great Mosque and the Church of St. George, and ordered the population to report there. Soon both places of worship, but especially the Great Mosque, were crammed full of men, women, and children. After a brief while, the women and children were sent home.

Still, this left most of the city to be taken, and there were only about 300 Israeli soldiers to take and hold it. It was full of local armed irregulars, while the remnants of the Arab Legion had barricaded themselves in the city’s police station.

By the next day, July 12, as Israeli forces were strengthening their hold on the city, two or three armored vehicles of the Arab Legion appeared on the northern edge and began firing in all directions. This encouraged an eruption of sniping and grenade-throwing at Israeli troops from upper stories and rooftops within the town, and from a second, small mosque only a few hundred meters from the armored-vehicle incursion. Israeli commanders feared a counter-attack by the Legion in coordination with the armed irregulars still at large in the city. The order came down to suppress the incipient uprising with withering fire. The Great Mosque and the church were unaffected, but Israeli forces struck the small mosque with an antitank missile.

After a half-hour of intense fire, the battle died down. Overnight, the Arab Legion withdrew from the police station, ending any prospect of an Arab counterattack. The next day, the Israeli military governor reached an agreement with local notables that the civilian population would depart from Lydda and move eastward. Israeli soldiers, acting under orders, also encouraged their departure. Within a few hours, a stream of refugees made its way to the east, emptying the city.

Shavit’s claim of a massacre is conveyed in passages relating to the “small mosque” (named the Dahmash mosque), in and around which the massacre supposedly took place. These passages lead the reader in a single direction: in Lydda, unarmed civilians were murdered wholesale by revenge-seeking soldiers, whose commanders then covered up the crime.

Because Shavit breaks up his telling of events with flashbacks, his narrative is choppy. Below, I have reassembled its key passages to tell his story in chronological order and in his own words, italicizing some passages for emphasis. In each instance, I then state the main “takeaway” point and explore why Shavit’s narrative poses problems—not only because some other sources contradict it (contradictions in historical sources are inevitable) but because among those sources are the very same people whose oral testimony forms the bedrock of Shavit’s reconstruction of events.

In what follows, all translations from Hebrew are my own.

2. A City Resists

Here is how Shavit’s reconstruction begins:

In the early evening [of July 11], the two 3rd Regiment [should be: Battalion] platoons [of the Yiftah brigade] are able to penetrate Lydda. Within hours, their soldiers hold key positions in city center and confine thousands of civilians in the Great Mosque, the small mosque, and St. George’s cathedral. By evening, Zionism has taken the city of Lydda.

Takeaway: The small mosque came under Israeli control on the first day, and it was among the places in which Israeli soldiers detained Arab civilians. There they would have been disarmed and placed under guard.

Problem: As long ago as November 1948, only months after Lydda’s conquest, the military governor Shmarya Gutman, in a published account, stated unequivocally that the city center wasn’t taken by evening: “We went to bed while only that part of the city around the Great Mosque and the church was held by the Israeli army. In the city itself, they had not yet penetrated.” Those Arab men who reported to the Great Mosque and the Church of St. George (parts of a single complex on the southern edge of the city) arrived unarmed, and Israeli soldiers put them under guard. But the small mosque, according to Gutman, was not a place where Israeli soldiers concentrated local inhabitants. Gutman emphasized the point in his 1988 film interview by the documentarian Uri Goldstein. The interviewer, trying to set the scene for later events at the small mosque, wanted first to establish its status.

Goldstein: This firing into the [small] mosque was after grenades were thrown from there?

Gutman: After the grenades were thrown. That’s the small mosque.

Goldstein: But people were detained there.

Gutman: There wasn’t a concentration of many people there. There they didn’t detain. That wasn’t a mosque where they detained. And from there they threw on the guys—who moved in formation of twos and threes—began to throw grenades on them.

Goldstein: It doesn’t add up. They detained people there, so how did they have grenades and all that?

Gutman: They didn’t detain people in that mosque. There were two mosques. In the small mosque, which was off on the side, from inside the courtyard they began to throw [grenades]. . . . It wasn’t a place of detention.

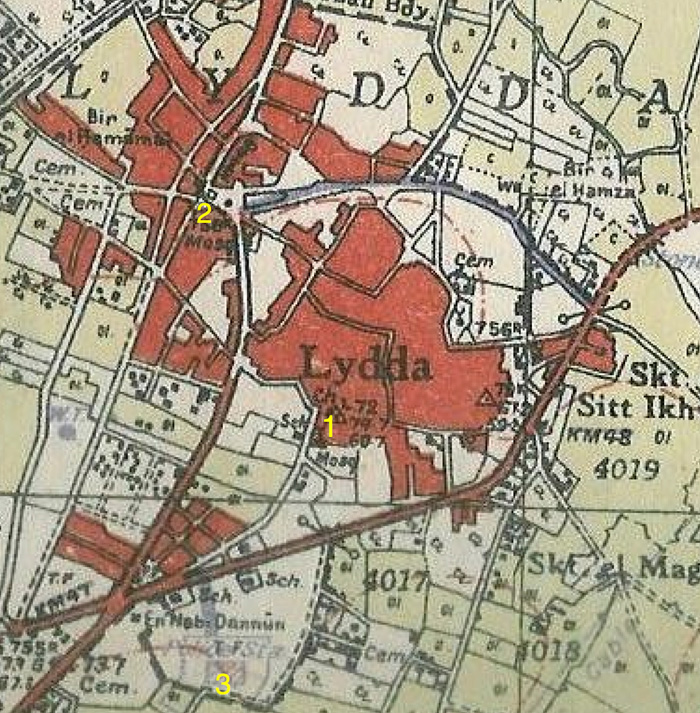

In this film interview, then, Gutman repeats four times that those in the small mosque weren’t detained there by Israeli forces, and that it wasn’t a place of detention. On the first night, the small mosque lay beyond the limited zone of Israeli control, which didn’t extend into the city proper. (On the British map embedded below and the high-altitude and low-altitude aerial photos found alongside, all showing pre-war Lydda, the area of the Great Mosque and the Church of St. George is marked by a “1” and the small mosque by a “2.” They are separated by the old city and the town market.)

If Gutman’s recollection is accurate, it means that Israeli forces had no idea who might be in the small mosque, why they had assembled there, or what weapons they might have.

In the second key passage, Shavit explains what caused things to go wrong the next day, July 12:

Two Jordanian armored vehicles enter the conquered city in error, setting off a new wave of violence. The Jordanian army is miles to the east, and the two vehicles have no military significance, but . . . some of the [Israeli] soldiers of the 3rd Regiment mistakenly believe them to mean that they face the imminent danger of Jordanian assault.

Takeaway: Since the conventional enemy army had retreated and now lay “miles to the east,” the Israeli forces were never under military threat.

Problem: Shavit makes no mention whatsoever of the Transjordanian Arab Legion’s continued presence not “miles to the east” but in Lydda itself, in the former British police station (marked on the map above with a “3″) just over a half-kilometer (roughly 0.3 miles) south of the Great Mosque. This structure—which today houses the national headquarters of Israel’s border police—is a British-built Tegart fort, designed to withstand attack. When Israeli forces entered Lydda, it is where the remaining Arab Legion contingent, reinforced by local police and foreign volunteers, barricaded itself.

Gutman, in his 1988 film interview, repeatedly refers to the Arab Legion forces in the police station as a looming threat. “From the police station,” he says, “heavy fire was directed at our men, and they couldn’t reach the streets approaching the place. That is, there was a feeling that there was a serious force there.” Even as the civilians streamed to the Great Mosque and the church, “all the time there was firing from the police station. They laid down heavy fire and there was a feeling of war.”

This was precisely the context in which the Israeli commanders interpreted the sudden appearance of the Transjordanian armored vehicles. As Gutman wrote a few months after the events:

It was clear to us that the city wasn’t conquered, and that at any moment the enemy’s armored cars could enter and put an end to our conquest. And above all, the police station was in the hands of the enemy. This was a great fortress, overlooking all of Lydda, from which it was possible to break into the city.

It was “in the midst of the firing from the police station,” says Gutman in his film interview, that “there appeared two armored vehicles from the olive groves, and they began to fire on our troops everywhere. It was something awful. We didn’t have any means against armored vehicles.”

The armored vehicles thus fit into a larger military context. In that context, the Arab Legion force in the police station remained a major concern. Even after the armored vehicles were repelled, Gutman did not believe the battle was over: “We didn’t know that the war was dying down. We were sure it would reignite, because they hadn’t left the police station, and the police station was a fortress.” Indeed, when the Israelis sent a delegation of Lydda notables to plead with the Legionnaires to surrender, the garrison fired on them, killing one leading notable and wounding a judge.

Only on the night of July 12 did the Arab Legion forces retreat from Lydda. Gutman:

The sturdy police building held by the enemy fighting force encouraged the city. This was a serious military force with great firepower. We hesitated to confront it. We didn’t have a large enough force to outflank it or attack it. So we decided to rain fire on it all night, to break the morale of the besieged. During the night, an offensive was launched, but without attempting to storm and take the station. The entire city shook from the booms of the shooting, and it sometimes seemed that it was being destroyed to its foundation.

Finally, the Arab Legionnaires ran out of ammunition and food and lost radio contact with their HQ. So they slipped away. “We must admit it,” concluded Gutman at the time: “They fought courageously, their command was serious, and they refused to surrender. We could have defeated them only with heavy weapons, but in those hours, such weapons were only in units fighting on the eastern front.”

In retrospect, the threat posed by the Arab Legion forces might seem insubstantial; but only in retrospect. Moreover, as Gutman emphasizes, it was the Legion’s abandonment of the police station that finally broke the spirit of Lydda’s inhabitants and persuaded its notables to embrace flight from the city. Here is Gutman’s contemporary report of his dialogue with the city’s notables:

I told them: “I have come now from the police station. There is no sign of the Arab Legion.”

They were dumbstruck and despairing. I learned from this that the city, and they, too, had still pinned their hopes on the police station. They were sure that with its help, they would still strike at the Jewish army.

They sank into deliberations. They still didn’t believe me.

I added for emphasis: “I’ve come just now from there. There isn’t a soul from the Legion. If you don’t believe me, open the window and see for yourselves!”

And they believed. They couldn’t but believe. Depression was etched on their faces. As though their wings had been clipped. They said not a word; they sat dumbstruck, and hung their heads.

Amazingly, both in his book and in the version published in the New Yorker, Shavit makes not a single mention of the police station or of the battle surrounding it. It is entirely absent from his own account of Gutman’s dialogue with Lydda’s notables. In Shavit’s conversations with Gutman, over “long days on [Gutman’s] kibbutz,” did the latter omit all reference to the police station? It seems improbable, but only Shavit knows the answer.

3. The Small Mosque

In a third passage, Shavit sets the scene for the mosque massacre as a revenge killing, done outside the chain of command and exceeding any calculation of military necessity:

An agitated young soldier arrives [at the church], saying that grenades are being thrown at his comrades from the small mosque. . . . [Gutman] realizes that if he does not act quickly and firmly, things will get out of hand. He suggests shooting at any house from which shots are fired, shooting into every window, shooting at anyone suspected of being part of the mutiny.

Takeaway: Gutman, despite his “firmness,” didn’t authorize specific action against the small mosque itself, presumably because it couldn’t be deemed a military target.

Problem: According to Gutman’s film interview, he didn’t just “suggest” returning fire against houses, windows, and suspect persons. Instead, he gave authorization specifically to strike the small mosque, which had now become a military target:

From a small mosque, they began to throw bombs at soldiers. Two of our guys were killed. They asked me: “What should we do?” I answered: “It is permissible to fire into the mosque.” And they did it.

Gutman also answered the primary objection to doing so, raised by the soldiers themselves:

They asked me: “It’s forbidden to harm the mosque, it’s a holy place.” I said: “A place from which they throw bombs must be taken out.” And they took it out, and it’s true that there were a few local casualties there.

So a counterattack on the small mosque, according to this interview of Gutman, was a military necessity, sanctioned by Gutman’s own authority as military governor. It was part of the improvised plan to suppress the uprising.

Next, in the fourth passage, Shavit zeroes in on his villain, “Bulldozer,” the operator of a bazooka-like PIAT (Projector Infantry Anti-Tank weapon) whom he has already portrayed at length as someone “traumatized” by war and who took a “delight in killing.” Shavit doesn’t give the name of Bulldozer, but he is plainly identifiable on the Palmah veterans’ website as Shmuel (Shmulik) Ben-David. Shavit:

When Bulldozer approaches the small mosque, he sees that there is indeed shooting. From somewhere, somehow, grenades are thrown. . . . One of the training-group leaders is wounded when a hand grenade, apparently thrown from the small mosque, explodes and takes his hand clear off. This incident provokes Bulldozer to shoot the antitank PIAT into the mosque.

Takeaway: Bulldozer wasn’t acting under orders, but instead allowed an “incident” to “provoke” him.

Problem: According to many sources, the counterattack against the mosque and the resort to the PIAT were done on orders from commanders who (naturally) viewed the enemy use of grenades not as “provocation” but as warfare. As we have just seen, the highest order came from the military governor, Gutman (“They asked me: ‘What should we do?’ I answered: ‘It is permissible to fire into the mosque.’”) Moshe Kelman, the 3rd Battalion commander, told the author Daniel Kurzman that it was his own idea to use a PIAT:

“We’ve got to pierce those walls” [said Kelman].

“But they’re a yard or a yard and a half thick,” an officer pointed out. “And we haven’t got any artillery.”

“We’ve got a PIAT.”

Kelman’s direct subordinate, Daniel Neuman, commanded the squad that moved toward the small mosque. In his 1988 film interview with Goldstein, with Bulldozer standing right beside him at the very spot in Lydda where the action unfolded, he explains how he ordered the PIAT strike:

We somehow dashed forward in formation . . . until we got to this place, where a grenade was thrown at us. Now we were in a double bind. There was the grenade, and we’re in a narrow alley, with no room to maneuver, and snipers continue to fire on us. So I looked around, I looked and surmised that from the building next to me, they threw the grenade. I pointed, I indicated to the PIATnik to fire a shell in there. He fired a shell.

Ezra Greenboim, a squad commander who preceded Bulldozer down the alley by the small mosque, would likewise recall summoning the PIAT operator:

From inside the mosque, grenades were thrown at us. I remember the shout: “Grenade!” We hit the dirt, because there wasn’t time to take cover. . . . Because we were certain—I say “certain,” maybe it wasn’t so—but at that moment because we were certain that grenades were thrown from the window of the mosque, we called the PIATist.

And from Greenboim’s testimony in the same interview by Goldstein: “Everyone hit the dirt. There were wounded from the grenade itself, and then the order came to fire the PIAT.”

Finally, Bulldozer himself also says, in the same 1988 interview, that he was expressly dispatched to the mosque with his PIAT:

I received an instruction to run immediately with the PIAT to the small mosque. We came running, under fire from both sides of the street, down this alley, where we’re standing now. Fire came from the houses, and especially from the second stories. Just as we were running, a grenade was thrown at us from the mosque—not from inside the building, but from its roof. Three people took shrapnel. I was lightly wounded by a fragment, which didn’t keep me from functioning.

Bulldozer adds that the appearance of the training-group leader (his name was Yisrael Goralnik) with a hand missing from the battle against the armored vehicles “certainly didn’t give us joy, so we decided to take out the mosque from which the shooting originated.” But even here, he doesn’t ascribe the decision to himself alone.

Indeed, in none of these accounts, including his own, did Bulldozer fire his weapon on his own initiative. Every soldier, in every account, recalls facing deadly grenades and receiving orders to take out their source. Only in Shavit’s account does the counterattack on the mosque become one “traumatized” killer’s on-the-spot reaction to a mere “provocation.”

In the fifth passage, Shavit essentially accuses Bulldozer of aiming at a civilian as opposed to a military target:

He does not aim at the minaret from which the grenades were apparently thrown but at the mosque wall behind which he can hear human voices.

Takeaway: Bulldozer passed over the minaret, a clear and perhaps legitimate target, preferring to zero in on the “human voices” of supposed detainees in the small mosque.

Problem: Bulldozer himself says in his interview with Goldstein that the grenade thrown at him came from the roof of the mosque—not the minaret—therefore presenting no target visible to the soldiers in the alley below. Greenboim, for his part, says they were certain the grenades came from a window, i.e., from inside the mosque itself, and it was at that window that the PIAT was aimed. There is no mention of the minaret in any of the testimony.

In researching this essay, I visited the small mosque to gain a sense of the site. That someone would have thrown grenades from so exposed a position as the mosque’s stout minaret, or would have remained there for even a moment if he had, beggars belief.

Sixth passage:

He [Bulldozer] shoots his PIAT at the mosque wall from a distance of six meters, killing 70. . . . And when the PIAT operator is himself wounded, the desire for revenge grows even stronger. Some 3rd Regiment soldiers spray the wounded in the mosque with gunfire. . . . They told [Bulldozer afterward] that because of the rage they felt at seeing him bleed, they had walked into the small mosque and sprayed the surviving wounded with automatic fire.

Takeaway: Palmah soldiers wantonly massacred wounded Arabs in a state of vengeful rage, and took pride in it.

Problem: Shavit’s account rests on what Bulldozer remembered being told by some of his buddies while he was hospitalized. Bulldozer himself didn’t enter the small mosque; he had sustained a gash to an artery in his neck from the recoil of the PIAT, and was evacuated immediately. Shavit seems not to have spoken to any Israelis who actually entered the small mosque.

In fact, at least three Israelis were eyewitnesses to the scene inside the mosque: Daniel Neuman, who commanded the counterattack; Ezra Greenboim, who was right alongside Bulldozer when he fired the PIAT and who afterward entered the small mosque; and Uri Gefen, who arrived after the counterattack and also entered the mosque. In 1988, Uri Goldstein interviewed Neuman and Greenboim on camera outside the small mosque; two years earlier, Gefen and Greenboim had shared their recollections in a long conversation, of which there is a transcript.

Daniel Neuman, the squad commander, gives this account of what happened after the PIAT attack:

Two doors or the gate—there was a large wooden gate—flew wide open. I rushed in with the unit, using grenades and submachine guns. And then it was quiet. Inside there were a number of people, I don’t know how many, some of them hit by our action, because what the PIAT left undone, the grenades did. We looked, we searched, we found weapons there. It wasn’t almost certain, it was absolutely certain, that they operated against us from there.

So it was standard combat procedure to follow up a PIAT attack with grenades and gunfire. During his interview of Greenboim, Uri Goldstein returns to the storming of the mosque, and veterans’ voices off-camera chime in: “After the PIAT, they went in with grenades. You don’t just walk in after a PIAT. You go in with grenades and fire.” To these soldiers, it was obvious that you didn’t just walk into a place where a surviving enemy might be waiting to kill you.

When Gefen and Greenboim finally did surveil the mosque, they were taken aback by what they saw. Gefen: “The people inside were hurt, hurt badly, some of them killed, some wounded, and it was a difficult scene.” Ezra Greenboim was also shocked by the sight. He couldn’t believe that a PIAT had done the damage he saw:

After the shot, I went into the mosque. And what I saw, very soon after it occurred, since nothing had changed in the meantime, was indeed a group of people, children, men, the elderly, in a condition I couldn’t define, and I couldn’t understand what had happened. I’d feared that the PIAT shell hadn’t even penetrated the building, because it hit a window bar, but possibly it did penetrate. . . . To this day, I don’t know what happened in the mosque. I can speculate. Maybe the PIAT hit some explosives on the site. Maybe it struck a pile of grenades that was in the mosque. I don’t think there was anyone there before us. I don’t think if they had been wounded in the [initial] conquest of Lydda, the same wounded people would have remained there. . . . The matter of the mosque dogs me; as I said, I don’t know what happened, but we didn’t do it.

Greenboim does relate a story that would have been worth including in Shavit’s account, both because of its poignancy and because of its relevance to the claim that Israeli soldiers sprayed the wounded in a spasm of vengeance:

In the passageway, I remember a wounded Arab on the ground, so badly wounded that I thought it would be an act of mercy to finish him off, because he was torn apart, and I said, this will be a last act of kindness that I can do for this Arab, who was unarmed. And just as I raised my Tommy gun and told the guys around me to move away, so they won’t witness the sight—and I, all agitated that I am going to do this, which is the most awful thing I’m capable of doing—the Arab looks at me and says in Yiddish: hob rahmones, that is, have mercy on me, but in Yiddish. These words in Yiddish stopped me in my tracks, I froze. Because at that very moment, I heard the hob rahmones of many, many Jews who came from over there [in Europe]. This use of Yiddish, which was the language of our people, from over there. . . . I didn’t [shoot], I couldn’t do it.

Greenboim, it should once again be emphasized, had been right there when Bulldozer was gashed by the recoil of the PIAT: “It was like [Bulldozer] had been slaughtered, he was wounded in the neck. A stream of blood flowed out of him, like a fountain.” And the same Greenboim then nearly shot an unarmed, wounded Arab with automatic weapon fire—exactly the scenario alleged by Shavit. But the situation was utterly different, the motive was anything but rage and revenge, and he didn’t shoot him.

There are, of course, discrepancies in the soldiers’ accounts. Gefen says some in the mosque were killed, some were wounded. Greenboim, by contrast, says most were unharmed but were pressed back against the walls in a state of shock. (This seems to contradict his report of his own shock at the extent of the carnage.) These must have been fleeting impressions: Greenboim also recalls that, before encountering the wounded Arab in the passageway, “I saw the sight inside [the small mosque], and I bolted out.” How many died from the PIAT attack versus the grenades and gunfire is beyond conjecture.

The soldier Uri Gefen shared with his comrade-in-arms Greenboim the lasting impression left by what they saw in the small mosque: “How many years does a man live? So all our days we will remember it, no helping it, whether we want to or not, we can’t escape from it—the small mosque.” But in the course of their long and frank conversation, there is no hint that anyone was killed in that place except in the course of combat.

As the small mosque is so central to Shavit’s narrative, it is hard to fathom why he didn’t make use of such eyewitness testimony, even if he didn’t collect it himself. At the very least, it adds layers of complexity that are so obviously (one is tempted to say “painfully”) missing from “Lydda, 1948.”

As a side note, it is also worth considering how the toll of 70 dead in the mosque may have entered Shavit’s account, where it is repeated five times. Shavit doesn’t give a source for this number, but it seems to have originated in his visit to Lydda in 2002, when he wrote an article about the present-day politics in the city. On that occasion he met an elderly Arab school principal, who would have been about twenty in 1948. Shavit, paraphrasing him: “Seventy were massacred there, they say. [The principal] doesn’t know himself, he didn’t see it with his own eyes, but that’s what they say. Seventy.”

In 1948, the military governor, Gutman, gave a different estimate: “The Arabs who threw bombs were struck with a PIAT, and 30 fell straightaway.” This is the casualty count often given in Israeli sources. Some Arab sources, in contrast, claim casualties in the hundreds. It’s not clear why Shavit prefers one account to another, why he doesn’t give a range of possible numbers, or, most importantly, why he repeats the figure of 70 dead five times over, firmly imprinting it on the mind of the reader as though it were a well-attested fact.

4. A Battle with Two Sides

Moving on directly from what happened inside the small mosque, we come to Shavit’s seventh passage:

Others toss grenades into neighboring houses. Still others mount machine guns in the streets and shoot at anything that moves. . . . After half an hour of revenge, there are scores of corpses in the streets, 70 corpses in the mosque. . . . In 30 minutes, at high noon, more than 200 civilians are killed. [In the New Yorker version: “In 30 minutes, 250 Palestinians were killed.”] Zionism carries out a massacre in the city of Lydda.

Takeaway: Palmah troops sank into a Zionism-inspired orgy of revenge killings of civilians, in numbers exceeding the most reliable estimates of those killed two months earlier at Deir Yassin.

Problem: In the book, Shavit writes of more than 200 dead, and in the New Yorker of 250. In the latter version, Shavit adds that the more specific figure is “according to 1948 by [the historian] Benny Morris.” Morris’s own source is a contemporary Israeli military summary of the conquest of Lydda, later published (in 1953) in the official history of the Palmah. More than any eyewitness testimony, it is this figure—especially when contrasted with the small number of Israeli casualties (four dead and twelve wounded)—that has given rise to the claim that what occurred must have been a massacre and not a battle. In Morris’s words, “The ratio of Arab to Israeli casualties was hardly consistent with the descriptions of what had happened as an ‘uprising’ or battle.”

But not all historians believe this body count to be reliable. The Hebrew University historian Alon Kadish, who has looked at the conquest of Lydda in depth, believes the estimate may be of Arab casualties for the entirety of the fighting over several days, and that “it is doubtful that the number of Arabs killed on July 12 reached 250 or even half that number.” Moreover, the official report does not label the dead as civilians—as Shavit does in the book—instead describing those killed as “enemy losses.” Even Morris (in his book on Glubb Pasha, the British trainer and commander of the Arab Legion) describes those killed more comprehensively as both “townspeople and irregulars.”

As for the most explosive element of Shavit’s claim—namely, that the action in the streets, like that at the small mosque, also had no basis in military necessity but was carried out in “revenge”—here he simply contradicts himself. He cites Gutman and Mula Cohen as ordering a harsh response, and the interviews I consulted confirm it. The decision to lay down intensive fire was made by commanders who estimated that they faced an emergency situation.

The brigade commander, Mula Cohen, used just that term in an interview during which he recalled issuing his orders. Told that the city had erupted in sniping, Cohen announced: “This is an emergency, fire in all directions; tell the men to enter the houses of the locals; anyone who walks about with a weapon is an enemy.” Nor does the revenge motif line up with similar orders given by the military governor, Gutman (in this case, as told by him to Goldstein): “We have to lay down fire on all the houses, and put an end to this business.”

In short, as in the case of the small mosque, so in the instance of the battle around it, soldiers were operating under orders to lay down heavy fire, even as they themselves came under fire. “There are still exchanges of fire in the town,” reported the Yiftah brigade to the overall HQ of the front. “We have taken many wounded.” The fight to repulse the Arab Legion’s armored vehicles, just 200 meters (approximately 220 yards) from the small mosque, was so chaotic that one Israeli private went missing and was never found. Brigade commander Mula Cohen thought the response had been proportionate:

We didn’t want to kill Arabs. In my opinion, and to this very day, I am sure we did what we needed to do, and no more than that. Of course, in such a situation, there are all sorts of deviations and sorts of things. But in no way was there mass killing.

Mula Cohen’s claim was that a few “deviations” didn’t constitute a “massacre” of 250, and this has been at the core of a very lively debate among leading Israeli historians of the 1948 war. Shavit gives no hint that such a debate exists. Benny Morris, citing the disparity of casualties, persists in calling the events a “massacre,” so Shavit invokes him. But there is another view, championed by Alon Kadish and Avraham Sela (in a book devoted to the conquest of Lydda), that the events of that day were a straightforward battle. Mordechai Bar-On has weighed the contesting views, finding merit in both sides of the argument but coming down largely on the side of Kadish and Sela. In short, Shavit, far from representing the consensus of scholarship, has taken one side in an Israeli debate and formulated it in the most extreme way—although his American readers would never know it.

After the fighting died down, the Israelis faced the issue of disposing of the dead. Shavit’s eighth and final passage:

News comes of what has happened in the small mosque. The military governor orders his men to bury the dead, get rid of the incriminating evidence. . . . At night, when they were ordered to clean the small mosque and carry out the 70 corpses and bury them, they took eight other Arabs to do the digging of the burial site and afterward shot them, too, and buried the eight with the 70.

Takeaway: Gutman, the military governor, knew that what happened at the small mosque was a crime, and sought to “get rid” of the evidence. So dehumanized by now were the Israeli soldiers that they could shoot anyone simply in order to cover up their crimes.

Problem: Shavit doesn’t explain why burying the dead would constitute a cover-up. He himself writes of the “heavy heat” and the “scorching heat” of July, which punished the fleeing refugees from Lydda the next day and which would have rapidly affected the corpses and heightened the urgent need to inter them. Nor does Shavit cite any eyewitness source for this tale of the murder of an Arab burial detail, with its obvious evocation of the Holocaust.

Apparently, Shavit failed to interview an Arab inhabitant of Lydda, aged twenty in 1948, who claimed to have participated, along with his brother and cousin, in a ten-man detail ordered to remove the bodies from the mosque—this, after a delay of several days. This Arab townsman, Fayeq Abu Mana (Abu Wadi‘), who was still living in Lydda decades later, described the task in a 2003 interview:

They said to go to the mosque and take the corpses out from there. How to take them out? The hands of the dead were very swollen. We couldn’t lift the corpses by hand, we brought bags and put the corpses on the bags and we lifted them onto a truck. We gathered everyone in the cemetery. Among them was one woman and two children. They said burn. We burned everyone.

Abu Mana, who passed away in 2011, obviously survived this grim task unharmed. There is even a photograph of him in the Lydda cemetery, pointing out where the bodies, according to him, were not buried but burned to ash. He numbered them at 70, all but three of them men, and he may have been the local source for that number. In his frequent retelling of the story—a more detailed version exists in Arabic—he makes no mention of the murder of anyone assigned to the detail. If his wife is to be believed, all were taken prisoner after finishing the job.

5. New Myths for Old?

Even after revisiting Shavit’s sources, we can’t be certain about what happened in and around the small mosque in Lydda on July 12, 1948. I don’t pretend to such certainty, nor do I pretend to have resolved the contradictions in the accounts I’ve examined. I’m a historian, but I haven’t made a study of the 1948 war, and I haven’t tracked down every source. There are no documents for this episode, only oral testimonies, with all their attendant hazards. Officers and soldiers contradict themselves, they contradict their comrades, and Israelis and Palestinians obviously contradict one another. But what I uncovered in just a few days of archival research was more than enough to reinforce my initial doubts about Shavit’s account, and should be enough to plant at least a seed of doubt in the mind of every reader of My Promised Land.

That seed may have sprouted even earlier in the editorial offices of the New Yorker, or at least in its fact-checking department. In the magazine’s abridgment, tellingly, we learn that Israeli soldiers “confined thousands of Palestinian civilians at the Great Mosque,” but the small mosque is omitted as a place of civilian detention. It is then mentioned in only three sentences: “Some Palestinians fired at Israeli soldiers near a small mosque.” “One [Israeli soldier] fired an anti-tank shell into the small mosque.” And finally: “But then news came of what had happened in the small mosque. The military governor ordered his men to bury the dead.”

But what supposedly did happen in the small mosque? About that, the New Yorker reader is left completely in the dark. Nor is there any mention there of Bulldozer, of 70 dead, or of the Arab burial detail and its alleged liquidation. These are strange omissions in an article whose very headline touts the Lydda “massacre” as a scoop. Do the omissions reflect a judgment that parts of Shavit’s story, and his numbers, weren’t sufficiently documented? David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, owes an explanation to his readers.

Beyond such disparities, highly suggestive in themselves, the fact is that not only are some of Shavit’s assertions impossible to verify, but by relying on the same eyewitnesses interviewed by Shavit (and on a few he should have interviewed), one can quite easily construct an entirely different story from his. That is the story not of a vengeful “massacre” committed by “Zionism,” but of collateral damage in a city turned into a battlefield. This is Lydda not as a “black box” but as a gray zone—a familiar one, since many hundreds of Israeli military operations in built-up areas have fallen into it.

It is in this gray zone, not in Shavit’s “black box,” that real complexity resides. But nowhere does Shavit give his readers a clue that anything in his dramatic narrative of Lydda is contested. To the contrary, at the end of his source notes is this assurance:

I read hundreds of books and thousands of documents. . . . To make sure all details are correct, oral histories were checked and double-checked against Israel’s written history. The exciting process of interviewing significant individuals was interwoven with a meticulous process of data-gathering and fact-checking.

The details are correct, then; the facts have been checked. The historian Simon Schama, in a gushing review, affirms that the book is “without the slightest trace of fiction.” And many of Shavit’s readers are understandably treating his book and this chapter as history. The book received the National Jewish Book Award in History, and the New Yorker ran the abridged chapter under the rubric of “Dept. of History.”

Yet Shavit, while claiming that he has followed a rigorous method, also tries to have it both ways: “My Promised Land,” he writes in those same source notes, “is not an academic work of history. Rather, it is a personal journey.” That inspires rather less confidence: one cannot make a “personal journey” to a day in 1948. Immediately after insisting that all the details and facts have been vetted, Shavit then adds still another caveat: “And yet, at the end of the day, My Promised Land is about people. The book I have written is the story of Israel as it is seen by individual Israelis, of whom I am one.” At day’s end, are we reading oral history after all? Or something still stranger—what Simon Schama, in his review, classifies as “imaginative re-enactment”?

It is this confusion that leaves My Promised Land even more vulnerable than the 1958 novel Exodus by Leon Uris, the last “epic” account of 1948 to seize the imagination of its Jewish and non-Jewish readers. If Exodus was misleading, at least its readers were forewarned that it was fiction. Shavit’s readers can’t be sure just what they are reading: “imaginative re-enactment,” the “story of Israel,” oral history, “epic history,” or “Dept. of History” history. Yet how it was written bears on how it should be read, and how many grains of salt the reader needs to add.

At the end of “Lydda, 1948,” Shavit suddenly entertains the thought that “Zionism” may not have committed the massacre after all: “The small-mosque massacre could have been a misunderstanding brought about by a tragic chain of accidental events.” What, then, was “Zionism” responsible for? It was, he writes, “the conquest of Lydda and the expulsion of Lydda.” These were “no accident. They were an inevitable phase of the Zionist revolution.”

It’s a debate worth having, but this statement follows by only a few pages the assertion that in Lydda, the massacre was what facilitated the expulsion. Putting a thought into the head of the military governor, Shmarya Gutman, as Lydda’s notables resign themselves to departing the city, Shavit writes: “Gutman feels he has achieved his goal. Occupation, massacre, and mental pressure have had the desired effect.” So perhaps the massacre was desired after all, perhaps even planned? There are those, among Palestinians and their supporters, who already claim that massacres invariably preceded expulsions, and so must have been willed no less than were the expulsions themselves.

Shavit seems to think he can deflect this reading of his Lydda chapter. “Let’s remember Lydda, let’s acknowledge Lydda,” he protests, “yet let no one use Lydda in order to doubt Israel’s legitimacy.” But of course that is precisely what many are already doing and will continue to do, citing and echoing the confessedly tormented Ari Shavit as they point accusingly not just at the actions of Israel’s soldiers but at the murderous intentions of Zionism itself, with Lydda as a prime exhibit in the ever-expanding criminal indictment against the Jewish state.

If Shavit is sincere in expressing alarm at the misuse of his account, he can take action. He can deposit his interviews in a public archive so that researchers may compare them with other interviews given by the very same persons—and with Shavit’s own account in his book. And he can conduct his own comparison. It isn’t too late to revisit the Lydda “massacre” and honestly flag the points of contention in the forthcoming paperback edition and in the anticipated translations into German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Hungarian, and Chinese. (He needn’t bother about the Hebrew edition; its reviewers will do the job for him.)

As for the grandees of American Jewish journalism who rushed to praise Shavit’s Lydda treatment, they have a special obligation to help launch the debate by sending readers to this essay. They know who they are.

Comments are closed.