If You Like Higher Prices, Enriched Cronies, and Weak National Security, Then You’ll Love the Jones Act By Scott Lincicome

http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/you-higher-prices-enriched-cronies-weak-national-security-then-youll-love

Lost in the never-ending debate about the KeystoneXL pipeline is great news for anyone who opposes cronyism and supports free markets and lower prices for essential goods like food and energy. Sen. John McCain has offered an amendment to repeal the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, also known as the Jones Act, which requires, among other things, that all goods shipped between U.S. ports be transported by American-built, owned, flagged, and crewed vessels.

By restricting the supply of qualified interstate ships and crews, this protectionist 94-year-old law has dramatically inflated the cost of shipping goods, particularly essentials like food and energy, between U.S. ports—costs ultimately born by U.S. consumers. Thus, the Jones Act is a subsidy American businesses and families pay to the powerful, well-connected U.S. shipping industry and a few related unions. For this reason alone, the law should die, but it turns out that the Jones Act also harms the very industry it’s designed to protect and, in the process, U.S. national security.

The Jones Act Inflates Shipping Costs for Americans

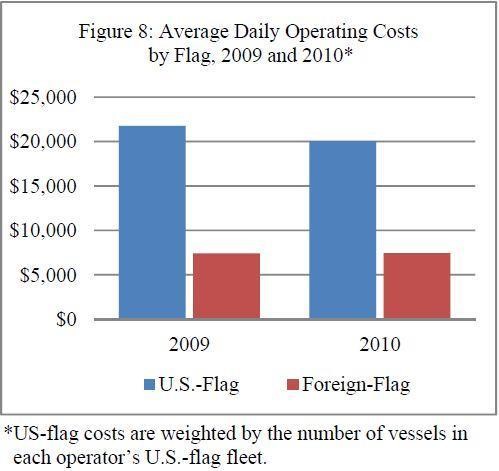

There is no question that the Jones Act inflates U.S. shipping costs. A 2011 Maritime Administration (MARAD) report, with input from the U.S. maritime industry, compared the costs of U.S.-flagged versus foreign cargo carriers, and found that the former far outweighed the latter due to the Jones Act and other U.S. regulations:

Carriers noted that the U.S.-flag fleet experiences higher operating costs than foreign-flag vessels due to regulatory requirements on vessel labor, insurance and liability costs, maintenance and repair costs, taxes and costs associated with compliance with environmental law… [T]he operating cost differential between U.S.-flag vessels and foreign flag vessels has increased over the past five years, further reducing the capacity of the U.S.-flag fleet to compete with foreign-flag vessels for commercial cargo…

Higher costs are precisely what you’d expect from an industry that has a “coastwise monopoly” on shipping, due almost entirely to the Jones Act. As a result, U.S. vessel operating costs are 2.7 times more expensive than their foreign counterparts.

Domestic unions and shipbuilders, with a bipartisan coalition of their congressional benefactors, vehemently deny that these outrageous shipping costs differences have any effect on the ultimate cost of U.S. goods that are transported on Jones Act vessels, but several examples belie such claims (and prove that, once again, basic economics still works).

First, there is ample evidence that the Jones Act distorts the U.S. energy market and raises domestic gasoline prices. As I noted last year:

According to Bloomberg, there are only 13 ships that can legally move oil between U.S. ports, and these ships are ‘booked solid.’ As a result, abundant oil supplies in the Gulf Coast region cannot be shipped to other U.S. states with spare refinery capacity. And, even when such vessels are available, the Jones Act makes intrastate crude shipping artificially expensive. According to a 2012 report by the Financial Times, shipping U.S. crude from Texas to Philadelphia cost more than three times as much as shipping the same product on a foreign-flagged vessel to a Canadian refinery, even though the latter route is longer.It doesn’t take an energy economist to see how the Jones Act’s byzantine protectionism leads to higher prices at the pump for American drivers. According to one recent estimate,revoking the Jones Act would reduce U.S. gasoline prices by as much as 15 cents per gallon ‘by increasing the supply of ships able to shuttle the fuel between U.S. ports.’

For these and other reasons, the Heritage Foundation just recently called for the complete repeal of the Jones Act as part of its new energy policy agenda.

Second, the Jones Act has particularly deleterious effects on water-bound U.S. markets like Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii. A 2012 report by the New York Fed highlighted the issue for Puerto Rico:

Available data show that shipping is more costly to Puerto Rico than to regional peers and that Puerto Rican ports have lagged other regional ports in activity in recent years. While causality from the Jones Act has not been established, it stands to reason that the act is an important contributor insofar as it reduces competition (shipments between the Island and the U.S. mainland are handled by just four carriers). It costs an estimated $3,063 to ship a twenty-foot container of household and commercial goods from the East Coast of the United States to Puerto Rico; the same shipment costs $1,504 to nearby Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) and $1,687 to Kingston (Jamaica)—destinations that are not subject to Jones Act restrictions… Furthermore, over the past decade, the port of Kingston in Jamaica has overtaken the port of San Juan in total container volume, despite the fact that Puerto Rico’s population is roughly a third larger and its economy more than triple the size of Jamaica’s. The trends are stark: between 2000 and 2010, the volume of twenty-foot containers more than doubled in Jamaica, while it fell more than 20 percent in Puerto Rico.

A 1988 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found similar harms for Alaska and the U.S. economy. Thus, the idea that the Jones Act doesn’t line the pockets of a few U.S. companies and unions at the expense of American families and businesses simply defies reality.

Regulating Industries Cuts Them Down

Supporters of the Jones Act often rebut these economic criticisms by explaining that the law is absolutely essential for U.S. national security, but these claims also fail the smell test. Consider first the enervation of the U.S. shipping industry itself. The above-referenced MARAD report shows a U.S. industry that has declined nearly to the point of extinction under the weight of the Jones Act and other regulations—a shameful outcome when you consider the history and importance of the U.S. Merchant Marine, which is a component not just of the United States economy, but also our national defense. Mariners in World War II faced the highest casualty rate of any other service:1 in 26 men went to their deaths on the sea. In 1950, ships waving the United States flag comprised 43 percent of the global shipping trade. Yet by 2009 the U.S. fleet had withered to 1 percent of the global fleet—while global demand for international shipping surged.

As of 2010, the picture was clear: there were 110 U.S.-flagged ships engaged in foreign commerce. Sixty of these ships were part of the Maritime Security Program. Notably, as of 2012 these ships receive a subsidy (naturally) to the tune of $3.1 million per ship, per year, to offset their higher costs. Compare this to the 540 shipsowned by American interests which flew a “flag of convenience”—typically that of the Marshall Islands, Singapore, or Liberia. Why such a dramatic difference?

While it is certainly not the only factor at play, this precipitous decline in the U.S. fleet’s standing is due in no small part to burdensome regulations which make American ships more costly and less competitive. The Jones Act requires ships engaged in the U.S. trade to be built in the country, but building a ship in the United States is exorbitantly expensive—three times the cost of a new ship built in Japan or South Korea. In nearly all cases it is far less burdensome to purchase an existing ship and reflag it rather than build new. And these burdens are before factoring the requirement to crew these ships with U.S. mariners, union men who unsurprisingly average more than five times the expense of a foreign crew. Indeed, the MARAD report identified labor costs as the single largest driver of the difference between U.S. and foreign carrier costs.

The Jones Act isn’t the only harmful regulation, not by a mile. One of the unfortunate realities of operating a massive ocean-going vessel full of complex machinery is that things inevitably require maintenance. These inconveniences often arise overseas and necessitate repairs in foreign countries. Lest you worry the government would be left with beak unwetted in this instance, fear not: 19 USC § 1466 to the rescue (link included if you’re having trouble falling asleep). This outgrowth of the Tariff Act of 1930 requires the master, or owner of a vessel, upon the ship’s return to a United States port, to declare to U.S. Customs any parts and services received onboard while in foreign waters. The ship owner is then required to pay an ad valorem duty of 50 percenton the dutiable vessel repair costs.

A few exceptions written into the law help mitigate this figure, at the further cost of man hours or maritime attorney fees. Free trade agreements between the United States and nations like Oman, South Korea, Singapore, and others help to alleviate these costs by allowing for almost total remission of duty for work performed in those countries. However, it’s hardly practical for U.S.-flagged vessels to perform the entirety of their maintenance in these countries when stays in port can be measured in hours. Vessel repair duties are situated to remain a significant, punitive cost of doing business as a U.S. cargo vessel. Even with this 50 percent duty, in the majority of cases it is still less expensive to make the repairs overseas and pay up rather than to perform the work in the United States. This also holds true for the acquisition of new ships.

Thus, under the Jones Act, shipping prices (as well as those for the goods shipped) riseand the U.S. fleet degrades. (For more on how the Jones Act imperils U.S. maritime security, see this helpful Heritage Foundation report.) It’s quite the double-whammy, and precisely what you’d expect from a protectionist law that thwarts the benefits of foreign competition. In short, the Jones Act has turned the U.S. merchant marine into a fleet of Ford Pintos and Chrysler K-Cars, all in desperate need of the kind of motivation only free market competition can bring.

To Top It Off, the Jones Act Worsens Emergencies

Moreover, the Act has proven to be a significant and costly obstacle in times of real emergency. Most recently, the deep freeze of 2014 saw New Jersey exhaust its supply of road salt, imperiling the lives of local travelers. Such salt was available in Maine, but it was delayed for days because of the requirement that only U.S. ships could engage in coastwise trade to carry the shipment—even though an empty foreign ship was available and headed to Newark. The government denied a request to waive the Jones Act and use the foreign ship to supply the much-needed road salt. By the time a Jones Act barge was found to carry the salt, the cost of the operation had grown by $700,000. Sorry about those icy roads, New Jersey, but the shipping industry and unions gotta get paid.

During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the governmentsimilarly refused to issue Jones Act waivers so foreign vessels could aid in the cleanup and containment. Despite several offers for foreign assistance during an ongoing ecological disaster, the government cited the Jones Act to justify turning them away. Many suspect that the Obama administration was reluctant to go against the pro-Jones Act labor unions (tr. every labor union) he needed to cement his re-election. It’s not a leap to say that such cronyism may have delayed the eventual resolution of the spill.

The Jones Act and its related statutes raise the cost of essential goods for American families and businesses; strangle the life from the industries they were designed to protect; jeopardize U.S. maritime security; and exacerbate the pain of major national emergencies. (They also are major irritant in foreign trade relations.) So why hasn’t Congress repealed these laws? Maybe we should ask the politicians and well-connected cronies who benefit from the current arrangement. I’m sure they’d be happy to explain.

McCain’s amendment to repeal the Jones Act is a common-sense solution to the problems facing a key American industry and the pain of the U.S. economy. The amendment, as well as any broader proposal to kill off the Act, deserves widespread support from conservatives and liberals alike. Efforts to dispense with this archaic protectionist boondoggle will no doubt meet fierce resistance from entrenched interests, labor unions, and opponents of free trade. However, those same groups stand only to benefit from efforts to make the U.S. fleet more competitive and less costly. American mariners have what it takes to compete on a global scale, and they should be given the chance. More competition translates to more opportunity, and perhaps the expansion and revitalization of a crucial sector of our economy. Where artificial monopolies and ancient restrictions can be removed, American labor, American business, and American consumers will have a chance to thrive.

Comments are closed.