Why David Petraeus Really Wants You To Shut Up About Islamism :Christine Brim

Christine Brim is a founder of Paratos LLC, a risk communications consultancy. Previously she served at the Center for Security Policy as a vice president and chief operating officer.

Petraeus’s attack was so over-the-top, no expression critical of Islamic doctrine would escape his censorship. Have you criticized mainstream Islamic doctrine or the laws of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates? You’re demonizing a religious faith. Do you object to authoritative Islamic doctrines justifying jihad, proclaimed by both Islamic governments and non-state Islamic militants alike? Stop toying with anti-Muslim bigotry; you’re just aiding “Islamist terrorists.”

Sadly, Petraeus’s attacks primarily undercut the foremost critics of Islamic doctrine: Muslim reformers, the group of Muslims who most need our support. A prominent young Muslim reformer, Shireen Qudosi, responded to his op-ed with this poignant tweet: “Petraeus doesn’t see that for much of the maddening world of Muslims and liberals, hate speech is conflated w/ truth.”

The theme of Petraeus’s op-ed, “Anti-Muslim bigotry aids Islamist terrorists,” was in line with a campaign to blame ISIS on Western critics of Islamic doctrine. For example, The Mirror: “ISIS wouldn’t be here if there wasn’t Islamophobia”; The Nation: “ISIS Wants You to Hate Muslims”; The Guardian: “Islamophobia plays right into the hands of Isis”; Salon: “After Brussels, far-right Islamophobes are doing exactly what ISIS wants them to do”; and last but not least, Hillary Clinton in The Daily Mail: “‘He is becoming ISIS’ best recruiter’: Hillary Clinton blasts Donald Trump for demonizing Muslims and using ‘bluster and bigotry to inflame people.”

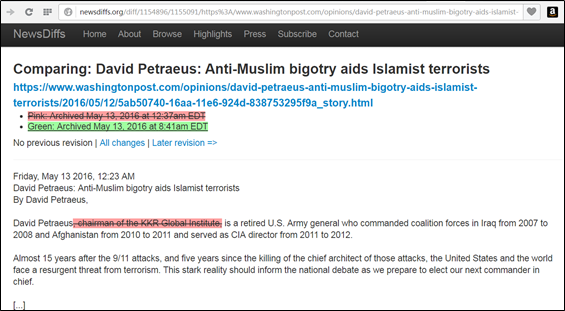

But in the curious case of Petraeus’s op-ed, what was deleted prior to publication is more interesting than what the Post finally published. Sometime early in the morning on Friday the 13th, these six words were deleted from the short Petraeus bio (known to editors as the ID) accompanying the piece: “chairman of the KKR Global Institute.”

Here’s a screenshot from the indispensable Newsdiffs.org website:

Explaining the deletion, Washington Post Opinion Editor Michael Larabee said, “The ID including the KKR phrase was not the final edited ID for the piece. I had decided on the shorter ID during the editing process, but unfortunately the longer ID was still on the Web text when it was published overnight. It was updated when it came to my attention first thing that morning.” Larabee later emailed, “We didn’t do a correction because there was no factual error to correct – both ID’s were accurate — and I can’t get into the internal process of how it came to my attention.”

Kristi Huller of KKR’s media office unequivocally stated Petraeus had requested the change. “General Petraeus regularly writes in his private capacity about non-investment specific issues and this was one of those instances. The Washington Post erroneously added the KKR affiliation. General Petraeus requested the update. KKR was not involved in the piece or the byline discussion with the Post.”

So why did Petraeus request that his KKR affiliation be removed? After all, he widely publicizes his KKR affiliation elsewhere. His LinkedIn page leads with his dual KKR roles: “General (Ret) David H. Petraeus joined KKR in June 2013 as Chairman of the KKR Global Institute. He was made a Partner in December 2014.”

Money Makes the World Go Round

Perhaps the Post should have let their readers judge for themselves if Petraeus’s financial interests in KKR, and KKR’s financial interests in the Middle East, were relevant to his op-ed demanding an end to criticism of Islam. KKR has been trying for the past seven years to enter private equity markets in Muslim-majority countries, especially in Dubai (part of the United Arab Emirates) and Saudi Arabia. During those same years, the governments of Dubai and Saudi Arabia hardened their laws against criticism of Islam at home, and increased their lobbying spending to shut down criticism of Islamic doctrine abroad.

Petraeus joined KKR in June 2013, six months after he had to resign from the CIA. As The New York Times noted in a 2015 profile of Petraeus, “private equity experts said his real value was his Rolodex. ‘Petraeus is kind of a door-opener,’ said one friend of Mr. Kravis, who insisted on anonymity to discuss private business matters. ‘If Petraeus helps Henry find a way to $100 million in investments in Kazakhstan or elsewhere, it’s a good deal for both of them.’”

KKR, a 40-year old global investment firm with $120 billion in assets under management, had begun as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., memorialized in Bryan Burrough and John Helyar’s superb 1989 book “Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco.” KKR first expanded into Europe and Asia, and in recent years they began their move into the Middle East.

In May 2009 the newly formed subsidiary KKR Middle East and North Africa (KKR MENA) received a license to operate from the Dubai International Financial Centre. Two years later, in June 2011, another new KKR subsidiary, KKR Saudi Limited, received an Arranging License from the Capital Market Authority (CMA) to seek investment opportunities in Saudi Arabia, as the first global U.S. private equity firm to enter the Saudi market.

KKR had hired Petraeus as chairman of the Global Institute for exactly these opportunities, as Henry Kravis announced in KKR’s May 2013 press release announcing the Petraeus appointment: “As the world changes and we expand how and where we invest, we are always looking to sharpen the ‘KKR edge.’” Petraeus would help with “investments in new geographies,” presumably in those Middle East and Central Asian countries he knew from his years as CENTCOM commander and CIA director.

Nothing to See Here, Invest Away

Petraeus got to work, presenting a sunny view of reforms in the region in a December 2013 interview with the PrivCap newsletter (video and transcript highlights): “Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco. . . in each of these countries there have been far more reforms than I think most people recognize. You have to understand the culture. You have to understand the conflicting tensions in these countries to appreciate how much, say, King Abdullah in Saudi Arabia has really done in a state where there is a lot of conservative sentiment.”

In January 2014, exactly one month after Petraeus’s speech lauding regional reforms, Saudi Arabia passed the Penal Law for Crimes of Terrorism and Its Financing. As the Washington Post noted at the time, the Saudis were already using execution and lashing as punishments for any criticism of Islam (blasphemy), attempts to leave Islam (apostasy), or criticism of the government.

In February 2014, in an act that helped the global fight against terrorism, the Saudis designated the Muslim Brotherhood and Hezbollah as terrorist organizations, but they applied the January terrorism law primarily against dissidents who wanted to reform Saudi Arabia’s Islamic doctrines. According to Human Rights Watch, the enforcement regulations for the new 2014 “terrorism” law included:

Sweeping provisions that authorities can use to criminalize virtually any expression or association critical of the government and its understanding of Islam…Article 1. Calling for atheist thought in any form, or calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which this country is based. [Article 2:] Anyone who throws away their loyalty to the country’s rulers, or who swears allegiance to any party, organization, current [of thought], group, or individual inside or outside [the kingdom]…

A total of seven articles criminalized free expression, with prison sentences ranging from three to 20 years. The Saudis used the law to go after dissident bloggers, journalists, human rights activists, lawyers, anyone who stood out. Enforcement was arbitrary, brutal, and effective. Any communications with “reformers” became criminal. An example: an eight-year prison sentence was given to a Saudi for posting tweets and YouTube videos supporting demonstrations by families of imprisoned dissidents, as well as for “his sarcasm toward the ruler of the kingdom and its religious authorities.”

The New York Times and even MSNBC reported on the Saudi crackdown. Petraeus, in spite of—or perhaps, because of—his influence and contacts in the region, was silent. But he was happy to talk about his new position at KKR, as he did at the Aspen Ideas conference on June 30, 2014. Here’s a bit of the transcript:

GEN. PATRAEUS: Well, I’m very fortunate frankly. I’m embarked in a portfolio of activities that are intellectually stimulating and rewarding, enjoyable. I’m the chairman of the Global Institute of KKR. It’s like being the director of the CIA for a global financial firm with a lot smaller staff, I might add.

SCHIEFFER: But a lot higher compensation, I would guess?

GEN. PATRAEUS: Well, as the villainous prime minister in the British House of Cards used to say, you might say that – I couldn’t possibly comment. (Laughter)

Petraus Brought In as the Middle East Melts

Meanwhile, the Middle East private equity market that KKR had entered so optimistically was throwing up barriers, according to KKR MENA head Kaveh Samie in a September 2014 Wall Street Journal interview. Valuations were set unrealistically high by the mostly family-owned local companies, who didn’t trust these foreign investment firms trying to enter the market. Layers of bureaucracy and regulations got in the way, including requirements for foreigners to hold only minority ownerships. KKR found it had entered a moribund deal market in the Gulf. Property prices and bank liquidity were dropping, dragged down by the global dive in oil prices.

Nonetheless, Petraeus was made a partner at KKR in December 2014, right before the full impact of America’s fracking boom hit the economies of Middle Eastern oil and gas producers.

In a search for investors for its funds, KKR began targeting family wealth firms around the globe. Reporters publicized Petraeus’s role as a kind of KKR secret weapon. In May 2015, Bloomberg reported “KKR Rolls Out Petraeus in $4 Trillion Hunt for Family Wealth.” In a mordantly amusing video at that link, Bloomberg’s Jason Kelly, struggling to explain why KKR would bring Petraeus into a meeting to raise money for a KKR fund, called him “a highly connected, global guy and he tells great stories…it’s a soft sell.”

Trump began his campaign the following month, and made his statement about a temporary ban on Muslim immigration in December 2015. The Middle East elites went ballistic. Government and business leaders in Dubai and Saudi Arabia threatened to pull their money out if Trump is elected. In December 2015, influential Dubai billionaire Khalaf Al Habtoor published an op-ed (“Ignore Trump’s bigotry at your peril”) condemning Trump and stating, “In light of the danger this person represents, I would urge the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (IOC) to issue condemnatory statements forthwith and all Arab leaders to consider placing Trump and anyone connected with his campaign or businesses on a blacklist.” On May 4, Habtoor called Trump “very dangerous” and a “loose cannon.”

Tensions were also escalating across multiple issues with the Saudis. Saudi lobbyists furiously opposed the release of the redacted 28 pages of the “9/11 Commission Report” that allegedly implicated certain Saudis in the 9/11 attack. In April, Saudi foreign minister Adel al-Jubeir threatened a sell-off of $750 billion in securities and assets before they could be frozen if the United States passed a bill stripping Saudis of immunity to lawsuits by 9/11 surviving families.

On May 6, one week before Petraeus’s op-ed was published, Saudi Prince Turki al-Faisal warned against Trump’s effect on U.S.-Saudi relations. According to the Washington Post, the Saudis have recently spent millions with public relations and lobbying firms to silence critics in the United States. The bill removing the Saudi’s immunity from lawsuits passed the Senate on May 16.

Context counts.

Capitalizing On a Government Career

The Washington Post opinion editor’s initial instinct to include Petraeus’s KKR affiliation was the right one, and it’s a shame Petraeus asked for its removal. The incident follows a well-worn path. In Washington, reputation is the drug of choice, dealt on every corner of the K Street lobbying corridor.

The typical case: a highly placed official with a sterling reputation retires, someone whose career gave him contacts with foreign governments and foreign business leaders. His reputation has a respectable public part, his resume, and a valuable private part, his contacts, especially foreign contacts who control emerging markets and have money to spend on lobbying. When this useful individual speaks at conferences or publishes an op-ed or testifies before the Senate, his past resume is all that is presented when he is introduced as a speaker or summarized in a Washington Post “ID” accompanying his op-ed.

But his current employers, partners, and clients? Not disclosed, and neither K Street customs nor government regulations require the disclosure. If his speech, op-ed, or testimony just happens to align with the interests of his employers, partners, clients? That’s a serendipitous coincidence, an irrelevancy. As KKR stated, “General Petraeus regularly writes in his private capacity.”

Anyway, what difference does it make? The rules are clear. If you’re inside the Beltway, you already knew, and you have no need to know if you’re anywhere else.http://thefederalist.com/2016/05/18/why-david-petraeus-really-wants-you-to-shut-up-about-islamism/#disqus_thread

Comments are closed.