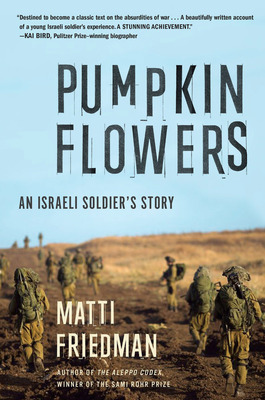

How Flower Songs Help Fight The Grief Of War By Matti Friedman

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/matti-friedman/songs-for-the-dead_b_14732870.htmlhttps://mosaicmagazine.com/picks/2017/02/what-israeli-and-canadian-war-songs-have-in-common/

Matti Friedman, a Canadian author and journalist, was raised in Toronto and now lives and writes in Jerusalem.

Have you seen the red, shouting for miles around?

Once there was a field of blood here, and now a field of poppies. …

Have you seen the white? Child, it’s a field of weeping

The tears have turned to stones, the stones have cried flowers

That fragment comes from a Hebrew song that became famous in 1971. It’s part of the secular canon of works known here in Israel as “memorial songs,” sung at military funerals and played on the radio on the country’s Remembrance Day.

I learned the song “There Are Flowers” not long after I arrived at a kibbutz in northern Israel from Toronto at age 17. The kibbutz kids discovered I could play guitar, and I was pressed into service to accompany a group of them in a rendition of “There Are Flowers” at a memorial ceremony.

I didn’t think much about it at the time, but later I became a soldier myself, and then a writer, and I’ve spent the past few years writing a book about war and pondering the way we talk about it. People engaged in conflict need to develop a language of grief.

People engaged in conflict need to develop a language of grief.

Religion has traditionally offered one, but in Israel’s early years people weren’t looking for the old mourning rituals that Judaism had to offer. Neither were they particularly interested in warlike language — “warriors,” “glory,” and so forth.

They turned instead to the natural world.

In “There Are Flowers,” the narrator admonishes a child not to pluck the flowers, whose lives are so brief to begin with. In Hebrew, “plucked flowers” is a term sometimes used for fallen soldiers, cut down before their time.

The song was written by the Israeli poet Natan Yonatan. Two years after it became popular, his own son, Lior, died in the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

That war was behind another of the country’s best-known memorial songs, written by a woman from a kibbutz called Beit Hashitta. Dorit Zameret wrote “The Wheat Sprouts Again” after the 1973 conflict consumed 11 men from her tiny community in the space of three weeks, a blow like the one suffered by those Newfoundland hamlets that lost all their young men on the first day of the Somme battle in 1916.

“The Wheat Sprouts Again” talks about the resilience of nature, which the author finds amazing and not entirely welcome:

“It’s not the same valley, it’s not the same house

All of you are gone, and you can’t come back.

The tree-lined path, the eagle in the sky,

And the wheat sprouts again …

How could it be, and how can it be, and how can it still be

That the wheat sprouts again?”

This language isn’t limited to Israeli songs. When I was drafted at 19 and found myself serving as an infantryman in a small guerrilla war in south Lebanon, I discovered that the army’s radio code for casualties was “flowers.” Dead soldiers were “cyclamens.” (The isolated outpost where I served also had a botanical name — Outpost Pumpkin.)

The language I encountered here seemed unique. But just a few years before, I’d been standing in a school cafeteria, the grey skies of a Toronto November out the window, reciting these lines, which I still know by heart:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place …

Great War poetry, at least the British variety, is full of flowers. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussel quotes a description of British soldiers as “gardeners camouflaged as soldiers,” writing: “Recourse to the pastoral is an English mode of both fully gauging the calamities of the Great War and imaginatively protecting oneself against them.”

Outside Israel, the use of floral euphemisms to mask the worst we inflict upon each other seems to have faded, though echoes remain. To honour dead soldiers Canadians wear a pin shaped not like a dead soldier, but like a poppy.

Here in Israel, the old pastoral language remains very much in use. It suggests a universal response to a universal kind of heartbreak — the absence of some young person that will persist long after the war, and the reasons for it, have faded.

Outside Israel, the use of floral euphemisms to mask the worst we inflict upon each other seems to have faded, though echoes remain.

The author of “There Are Flowers” didn’t share a language with John McCrae of Guelph, Ont., but I think they would have understood each other perfectly. They knew some things simply can’t be described.

Matti Friedman’s Pumpkinflowers, is nominated for the RBC Taylor Prize. He spoke about the book earlier this year to Politics and Prose in the United States.

Comments are closed.