The Hollywood Darling Who Tanked His Career to Combat Anti-Semitism By Edward White

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/03/the-courageous-unpopular-activism-of-ben-hecht/

One December day in 1939, Frank Nugent, a film critic for the New York Times, took his seat at the premiere of Gone with the Wind and waited for the carnage to unfold. So long and overblown had the movie’s ad campaign been that Nugent was sure it was going to be a turkey. When that proved not to be the case, he was stunned. “We cannot get over the shock of not being disappointed,” he wrote in his review the next day.

In truth, Gone with the Wind had come perilously close to being just the kind of disaster Nugent had foreseen. Three weeks into shooting, the producers shut down production, fired the director, and hired Ben Hecht to rewrite the script. Hecht was known as the “Shakespeare of Hollywood,” for his ability to knock out clever, crowd-pleasing work in the time it takes most writers to sharpen their pencils. But this was a tall order even for him: he’d never read Margaret Mitchell’s novel and had just seven days to dismantle and rebuild an epic blockbuster. The fact that he did it—fueled, so he claimed, by nothing but bananas and salted peanuts—might seem evidence of his remarkable talent. Hecht himself cited it as proof of the rank absurdity of Hollywood. Despite authoring dozens of successful films and earning six Oscar nominations, he dismissed Hollywood as a “marzipan kingdom” populated by idiots, responsible for an “eruption of trash that has lamed the American mind and retarded Americans from becoming a cultured people.”

Hecht gave that lacerating verdict in his autobiography, A Child of the Century (1953), listed by Time in 2011 as one of the hundred best works of nonfiction published since the magazine’s founding in 1923. Written in the rambunctiously opinionated style of Hecht’s hero, H. L. Mencken, the book deals with Hecht’s eclectic life as a literary critic, novelist, and playwright. He was intimidatingly prolific, and always provocative. His second novel, Fantazius Mallare (1922) landed him in court on an obscenity charge; a later novel, A Jew in Love (1931) had him labeled as a self-hating Jew. Hecht shrugged off the controversies; bigger strife lay ahead.

As his career in Manhattan and Hollywood climbed to new heights of critical and commercial success, he suddenly swerved onto an entirely unexpected path: revisionist Zionism. During World War II, Hecht sabotaged his Hollywood career by castigating the U.S. and its citizens for failing to stop the Holocaust.

As his career in Manhattan and Hollywood climbed to new heights of critical and commercial success, he suddenly swerved onto an entirely unexpected path: revisionist Zionism. During World War II, Hecht sabotaged his Hollywood career by castigating the U.S. and its citizens for failing to stop the Holocaust.

It was 1939, the climax of the so-called golden age of Hollywood. In addition to Gone with the Wind, cinema audiences that year were treated to The Wizard of Oz, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Of Mice and Men, Stagecoach, and Wuthering Heights, the latter two of which Hecht also wrote. But as Hollywood cheered its successes, safe in its bubble of unreality, Hecht’s restless gaze switched to Europe and the increasingly frequent and horrific reports of Jewish persecution. The desperate situation stirred in him a sense of belonging and duty to his fellow Jews that he’d never felt before. So, Hecht did what he always did when something got under his skin: he sat himself down and picked up his pen.

*

Hecht came of age alongside the ambulance chasers, muckrakers and polemicists of Chicago. In 1910, he arrived in the Windy City as a sixteen year-old runaway from small-town Wisconsin and discovered it to be just as Upton Sinclair and Theodore Dreiser had described: dirty, dangerous, and vibrating with supercharged ambition. On his reporter’s beat, he “haunted streets, whorehouses, police stations, courtrooms, theater stages, jails, saloons, slums, madhouses, fires, murders, riots, banquet halls, and bookshops,” and saw “people shot, run over, hanged, burned alive, dead of poison, crumpled by age.” Eventually, these things served as source material for plays and scripts, including the mob film Underworld, for which he picked up a statuette at the inaugural Academy Awards in 1929. As was often the case with his work in Hollywood, the success of Underworld astonished him; he’d been so aghast at the final cut of the picture that he reportedly asked to have his name removed from the credits.

After his apprenticeship in Chicago, Hecht moved to New York in the early twenties in pursuit of literary greatness. In 1926, Herman J. Mankiewicz, a screenwriter friend living in Los Angeles, wrote him a letter that read, “Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.” In need of money, Hecht moved. While the sunshine was wonderful, and the parties diverting, he loathed Hollywood, partly because he thought most of its films were execrable, but mainly for its fakery, hypocrisy, and moral cowardice. He reserved special contempt for “the hollow-headed big boss,” the philistine ogres in charge of the studios who filled their movies with preaching moralism, but in private treated everyone like dirt. “Men who have been the targets of rape and bastardy charges and who make seduction a profession remain honorable figures in Hollywood society.” Some things, it seems, never change.

During the roaring twenties, Hollywood’s vapid silliness seemed of a piece with the times. But when the darker days of the thirties arrived, Hecht began to despair at the studios’ inability to engage, on or off screen, with world-changing events. In particular, he was infuriated by the reticence to address the rise of the Nazis, especially as so many Jewish people of East and Central European descent were thriving in the industry. According to the film historian Thomas Doherty, the first Hollywood movie to directly engage with events in the Third Reich was Confessions of a Nazi Spy, released in 1939, after the invasion of Czechoslovakia. “In that year,” said Hecht, alarmed by the situation abroad and the indifference of his colleagues at home, “I became a Jew and looked on the world with Jewish eyes.”

Having never been active in politics, or even a vaguely observant Jew, Hecht began to write articles about the plight of European Jewry, and joined the Fight for Freedom Committee, a pressure group urging American involvement in the war. Using his First Amendment rights for these causes brought him to the realization that he’d never been a truly active citizen until now; “in 1939 I became also an American,” he said.

In April 1941, he wrote a piece titled “My Tribe Is Called Israel” in his column for P.M., the liberal New York newspaper, defending his efforts to “increase generally the Jew consciousness of the world,” and castigated “Americanized Jews” for failing to join him out of fear that they would appear to value Jewish lives more than American ones. It was lucid and strident invective that teetered on the vituperative—a typical Hecht opinion piece—and it caught the attention of the so-called Bergson Group, a small network within the U.S. who sought to advance the agenda of Irgun, a paramilitary organization fighting to establish a free Jewish state across the entirety of the historical land of Israel. The group was led by Peter Bergson (born Hillel Kook), a charismatic twenty-five-year-old Palestinian who sensed in Hecht a potential ally. Bergson reached out and arranged a meeting at the Twenty One Club, Hecht’s favorite Manhattan hangout.

A “force of nature” with a “small blonde mustache, an English accent and a voice inclined to squeak under excitement” was Hecht’s impression of Bergson after that first encounter. They were an odd couple, but a perfect match, each as outspoken and single-minded as the other. Though Hecht was insistent that he was “un-Palestine-minded,” he agreed to do what he could to put the Jewish persecution into the spotlight. It was the start of an exceptionally fruitful relationship. Bergson injected a radical sense of purpose into Hecht’s work; Hecht supplied bracing, high-profile propaganda that catapulted Bergson’s causes into the American mainstream.

The meeting with Bergson thrust Hecht’s campaigning into a new gear. On behalf of the Fight for Freedom Committee, he and Charles MacArthur devised the pageant Fun to Be Free, staged in front of seventeen thousand people at Madison Square Garden in October ’41, calling for a preemptive American strike against Nazi Germany. When Pearl Harbor shook the nation two months later, Hecht might’ve thought the task of attracting people to the cause of Europe’s besieged Jews would become easier. According to his testimony in A Child of the Century, it remained ferociously difficult.

In February 1943, Bergson helped him make contact with the activist Chaim Greenberg, who passed on revelatory research about the extent of the Holocaust. Hecht wrote an article for The American Mercury titled “The Extermination of the Jews.” It was swiftly picked up by Reader’s Digest and garnered huge attention. Hoping to capitalize on the publicity, Hecht arranged a meeting of thirty of New York’s most prominent Jewish writers. After he gave an impassioned speech asking them to use their pens to attack Germany, Hecht recalls that most of the room turned on him. He was accused of idiocy and recklessness. At a time when American soldiers were losing their lives in huge numbers, he was told, drawing attention to the suffering of Jews in Europe would only generate anger toward Jews in the U.S. Edna Ferber asked Hecht on whose orders he was acting, Hitler’s or Goebbels’s?

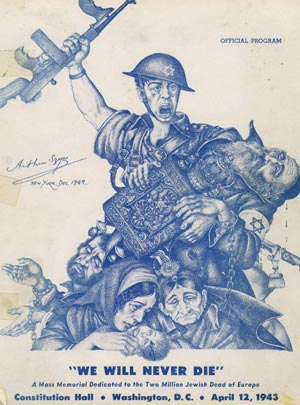

Undeterred, Hecht teamed up with the composer Kurt Weill and the producer Billy Rose to stage We Will Never Die, an extravaganza at Madison Square Garden that told the American public about the Holocaust. It featured a full orchestra, a choir, lavish scenery, and a gigantic cast of performers, including Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Leonard Bernstein, Stella Adler, and a teenaged Marlon Brando. Hecht even managed to persuade a hundred Orthodox rabbis “to commit sacrilege” and appear on stage. It was put together in less than a month and was an unqualified triumph. Demand for tickets was so high that they put on an extra performance and broadcast it through loudspeakers to a crowd of twenty thousand that gathered outside the sold-out venue. Governor Dewey pronounced the day, March 9, 1943, a moment when all New Yorkers should “offer prayer to Almighty God for the Jews who have been brutally massacred.” The show toured the country, picking up many influential supporters along the way, including several members of Congress. When President Roosevelt announced the formation of the War Refugee Board a few months later, Hecht’s pageant seemed like a turning point, the moment when it became impossible to ignore Europe’s abandoned Jews. It’s estimated that around two hundred thousand lives were saved as a result of the board’s work.

Yet Hecht was unsatisfied. He thought FDR’s actions were too little too late, and was dismayed at how much effort it had taken to rouse people’s concerns about genocide. As the war reached its bloody denouement, Hecht came to believe that Bergson was right: the only way to secure the safety and dignity of the world’s Jews was to establish a homeland in Palestine. When Irgun resumed its military operations against the British rulers of Mandate Palestine in 1944, Hecht agreed to defend and promote its cause within the United States. “I had no interest in Palestine ever becoming a homeland for Jews,” he recalled of the time before he began his association with Bergson. “Now I had, suddenly, interest in little else.”

Irgun was a deeply controversial group, even among many committed Zionists, who thought them wild, violent radicals who damaged rather than strengthened the chances of building a Jewish state. Hecht admitted that his attraction to them was rooted in the fact that they exhibited a type of bold and defiant Jewishness that countered all the ancient stereotypes. What the British government perceived as unspeakable acts of terrorism, Hecht recast as the awakening of a Jewish identity that had laid dormant for millennia. “Here were Jews who did not believe in the master plan of submitting always to injustice and then patiently removing it as one removes burrs from a dog’s body,” he said. In Irgun’s scheme, Jewish people would no longer apologize for their existence and push their Jewishness to the background. Hecht had seen that happen, in ways large and small, his whole life. It was true even in Hollywood, where many of the biggest stars of the day—Edward G. Robinson, Melvyn Douglas, Lauren Bacall—had changed their names so as not to appear “too” Jewish. In the future that Irgun envisioned, such timidity would be unthinkable.

Hecht wrote the play A Flag Is Born in support of Irgun. It was produced by Peter Bergson’s American League for a Free Palestine, starred Marlon Brando as a Holocaust survivor, and was advertised as “1776 in Palestine,” with Hecht positioned as a latter-day Tom Paine. The success of the play, on Broadway and on tour in cities across the country, raised the better part of a million dollars with which Bergson bought Igrun a ship to illegally transport hundreds of Holocaust survivors to Palestine. It was named the SS Ben Hecht. Ultimately the mission failed; the British Navy captured the ship and sent the refugees to a prisoner camp in Cyprus. But Ben Hecht was now synonymous with the struggle for a Jewish homeland and arguably the most celebrated supporter of Irgun in the United States. He couldn’t have been prouder, though—Hecht being Hecht—he couldn’t shake the warning that Mencken had given him years before: “the leader of every cause is a scoundrel.”

*

After A Flag Is Born, Hecht’s defenses of Irgun grew increasingly astringent. In a full-page newspaper advert in May 1947, he taunted the British government, called them the real terrorists of Palestine, and had a message for Irgun’s fighters:

Every time you blow up a British arsenal, or wreck a British jail, or send a British railroad train sky high, or rob a British bank, or let go with your guns and bombs at the British betrayers and invaders of your homeland, the Jews of America make a little holiday in their hearts.

The following year, Hecht’s films were officially boycotted in the UK, which severely harmed his career in Hollywood, though he wore the injury as a badge of honor, calling it “the best press notice I had ever received.” He understood also that the boycott was a futile gesture from the British, coming as it did a few months after the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel. Hecht should’ve been overjoyed at that event, but the new Israeli nation led by David Ben-Gurion disavowed Irgun, its methods, and its creed. Ben-Gurion said plainly that “Irgun is the enemy of the Jewish people.” Hecht was disgusted. It was, he thought, as though the United States had rounded on Washington and the Continental Army once the Revolutionary War had been won. His time as a propagandist was over.

Britain’s boycott against his films ended in 1951, making it easier for Hecht to work in Hollywood again. He wrote for Rock Hudson on the 1957 version of A Farewell to Arms, and for Brando on Mutiny on the Bounty, though he didn’t think much of either movie. In his dotage, he made a final, brief, reinvention as a TV talk-show host, interviewing a fascinating range of people, including Eartha Kitt, Salvador Dalí, and Sugar Ray Robinson. The show was supposedly canceled because of Hecht’s insistence on talking about sex, drugs, religion, and various other things you weren’t meant to discuss on fifties TV. He peppered Jack Kerouac with questions of that sort during one episode, receiving little but honey-voiced giggles in reply. “I could write a book about the way you’ve lived,” said Kerouac, probably unaware that Hecht had already done that, too.

Britain’s boycott against his films ended in 1951, making it easier for Hecht to work in Hollywood again. He wrote for Rock Hudson on the 1957 version of A Farewell to Arms, and for Brando on Mutiny on the Bounty, though he didn’t think much of either movie. In his dotage, he made a final, brief, reinvention as a TV talk-show host, interviewing a fascinating range of people, including Eartha Kitt, Salvador Dalí, and Sugar Ray Robinson. The show was supposedly canceled because of Hecht’s insistence on talking about sex, drugs, religion, and various other things you weren’t meant to discuss on fifties TV. He peppered Jack Kerouac with questions of that sort during one episode, receiving little but honey-voiced giggles in reply. “I could write a book about the way you’ve lived,” said Kerouac, probably unaware that Hecht had already done that, too.

Edward White is the author of The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America.

Comments are closed.