Ritchie’s Boys and the Men from Zion By Matti Friedman

https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/2930/ritchies-boys-men-zion/?login=1517483688

Had you happened by a cave outside a certain kibbutz in British Palestine in late 1941, you would have been startled to find a small group of Nazi soldiers singing German songs by firelight under swastika flags. This wasn’t an advance unit of a Wehrmacht invasion force, though at the time the Afrika Korps wasn’t far away. It was the “German Section,” an outfit run by the British Special Operations Executive and the Palmach, the Jewish militia, and its members were German Jews who could pass for “Aryans.” Their job would be sabotage and subterfuge after the arrival of the German army in Palestine, which seemed imminent.

General Rommel and his Afrika Korps never got to Palestine, of course, so the German Section was never activated. But the image of those Jewish soldiers in Nazi uniform—young men forced from Germany because they weren’t Germans who then became useful because they were Germans—came back to me as I read Bruce Henderson’s Sons and Soldiers. Henderson tells the parallel story of a group of young Jews who barely escaped the Third Reich, reached a new homeland in America, and ended up putting their former identities and languages at the service of the U.S. Army as combat interrogators in Europe.

Before deploying as Americans to fight their former countrymen, Henderson writes, the soldiers passed through a U.S. Army intelligence installation in rural Maryland that included a mock German village and a theater for propaganda training, including staged Nazi rallies. Drawing their name from the strange base, Camp Ritchie, the soldiers became known—to the extent that they’re known (I’d never heard of them before reading this book)—as the Ritchie Boys.

Henderson introduces us to interrogators such as Werner Angress, who fled Germany as a scared teenager and returned from the sky with the 82nd Airborne. We meet Victor Brombert, whose family fled Germany for France after the rise of the Nazis and then had to keep running. He ended up returning to the Paris neighborhood of his youth in 1944 as a soldier in Patton’s army. When Brombert went looking for a girl he’d loved, he was told her fate in one word: Déportée.

With its population of soldiers of different nationalities preparing for the different battlefields of the world war, Camp Ritchie was a haven for Americans with strange backgrounds and accents, “a cacophony of foreign languages.” But military life wasn’t all friendly: Angress, for example, while still in a regular U.S. infantry regiment, spent time in something called an “alien detachment” because of his German identity, along with other foreigners denied weapons and relegated to cleaning latrines. “At night,” Henderson writes, “drunken soldiers coming back from town would curse loudly at them, calling them ‘Nazi pigs’ and worse.”

At the same time, once in Europe after the Normandy landings the Ritchie Boys were running unique risks, because if they were caught their fate wasn’t that of regular POWs. Henderson tells us about Kurt Jacobs and Murray Zappler, who fell into German hands during the setback in the Ardennes. When their captors identified them as German Jews, they were separated from the other Americans and shot. Through all of this the Ritchie Boys came to be seen as a crucial part of the American invasion force, delivering fresh information from captured Germans in time to save American lives. Sons and Soldiers presents this unfamiliar history for the first time, and a great deal of research is on display. The approach to the material, however, is more shotgun than sniper rifle; the cast is unwieldy and the plotlines numerous, which makes an important, fascinating story a little harder to follow than it should be.

Our appreciation for stories of Jewish bravery in those years sometimes obscures the fact that as a group Jews were powerless, reduced to begging others for a chance to bear arms. The Ritchie Boys joined the fight by embracing America and lived their lives as Americans afterward. That was one Jewish choice, one of the few available to those fortunate enough to remain alive.

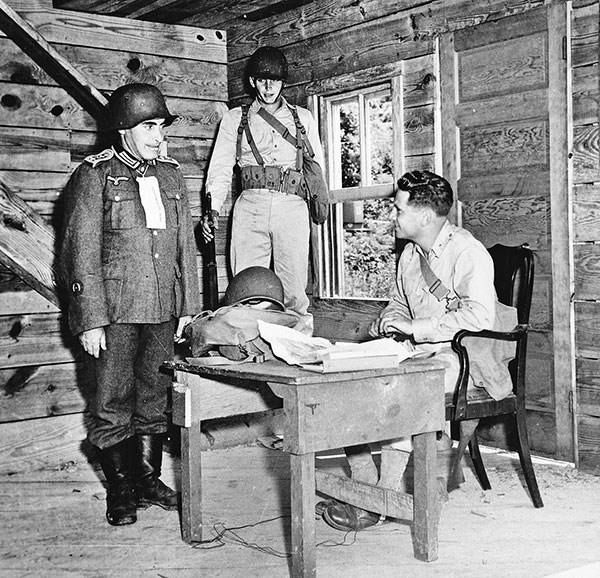

Former Dachau prisoner Martin Selling questioning German prisoners near the front in France, 1944. (Courtesy of U.S. Army Signal Corps.)

A second new book, Rick Richman’s Racing Against History, examines a more radical option—Zionism—by describing three visits by Zionist leaders to the United States in the desperate year of 1940. Chaim Weizmann, David Ben-Gurion, and Vladimir Jabotinsky stepped off ocean liners in New York that year, hoping to sound an alarm about the fate of Jews in Europe and to encourage the creation of a Jewish force to fight in the war. This was tricky, because the United States was still neutral, and American Jews weren’t sure how much they could help without endangering their own fragile position at home. Arriving separately and often at odds with each other, the three Zionist politicians addressed rallies, met important people, gave interviews, and wrote down their impressions, leaving material that Richman ably mines for this concise and illuminating account.

The three emissaries represented different ideological streams and rhetorical styles. Weizmann, the future Israeli president, a veteran of the back rooms of the British Empire, comes across as statesmanlike and cautious. Ben-Gurion, the future prime minister, is direct, practical, and preoccupied with Zionist politics. The Revisionist leader Jabotinsky speaks most clearly about the coming catastrophe and the urgency of Jewish self-reliance, seeming alarmist at the time and prophetic in retrospect.

All three failed to create a Jewish fighting force. But in Richman’s distillation of this little-remembered moment, we meet thoughtful people dealing with a key question that is also present between the lines in Sons and Soldiers: How should Jews best wield power and protect themselves in a world that tends to be predatory or indifferent? It’s a question that remains topical, if not pressing.

The Ritchie Boys practice their German-language prisoner interrogation skills on mock prisoners at Camp Ritchie. (Courtesy of NARA.)

Of the three leaders in Racing Against History, Weizmann was the most careful in his public utterances. He grasped the danger of the perception that world war was being waged for Jewish interests and preferred the quiet maneuver. He privately lobbied Chamberlain, the British prime minister, to accept “Jewish manpower, technical ability, resources” and was politely turned down. He privately lobbied for 20,000 permits to Palestine for Jewish children from Poland and was politely turned down. In America, he wrote, even mentioning what was happening to Jews in Europe might be “associated with warmongering.” American attitudes, he found, had “no relation to the grim realities which today face humanity at large and the Jews in particular.”

American Jewish thinkers of the time, Richman reminds us, included rabbis such as David Philipson of Cincinnati, who regarded the Jews as a universal people and the Land of Israel as “an outgrown phase of Jewish historical experience.” In an autobiography, the rabbi wrote: “Every land is the homeland for its Jews—the United States for me, as England for my English Jewish brother, France for my French Jewish brother, and so in every country.” Those lines, Richman notes, were published in 1941, with Europe under Nazi occupation.

In this volume, the sharpest contrast to Weizmann’s style is offered by Jabotinsky, who was outspoken about his impatience:

The old fallacy, the curse of our past, has been revived: that there is no Jewish problem; that all our troubles can be cured en passant by general measures of progress, and there is no need to worry about any special remedies. The allied victory will ensure democracy and equality . . . and that will be enough for the Jews.

Jabotinsky wanted a Jewish army raised immediately and said so, even though the mainstream American Jewish leadership called him a “militarist” and published a pamphlet warning against his views. In the pages of the Forward, editor Abraham Cahan mocked him as a “naïve person and a great fantasizer.” There was no need for Jabotinsky’s Jewish army, Cahan thought, and the Jewish problem would be solved not by a Jewish state but by an allied victory and democracy: If “true democracy exists, there is no place for anti-Semitism.” In other words, the way forward was to be American citizens and soldiers, like the Ritchie Boys.

Recent events in Europe and America would seem to suggest that anti-Semitism does, in fact, have a place in democracy; the English-language descendant of Cahan’s own Forward, for example, recently printed a bizarre op-ed by a Jewish supporter of an anti-Jewish boycott expressing sympathy for some of the views of an American neo-Nazi. The old idea of “Jewish warmongering,” about which Weizmann was so careful in 1940, is still current, as evidenced by the flap in September over a tweet by Valerie Plame, the former CIA agent, suggesting just that. And though the Zionist plan succeeded and there is a Jewish army, the normalization of the Jews has failed to materialize and their existential fears continue. Both the Ritchie Boys and the three Zionist leaders profiled in these books might be surprised how much the questions of their times remain unresolved 70 years later.

Comments are closed.

Comments