The tech war that isn’t US tech curbs on China bend to market reality David Goldman

https://asiatimes.com/2020/12/the-tech-war-that-isnt/

Washington last week added China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) to the “entity” list that requires US companies to get special permits to trade with it, rattling the Chinese chipmaker’s stock price. But China hawks in the US Senate complain that the wording of the new rules makes them easy to circumvent, and allege that the Commerce Department bowed to the “parochial commercial interest” of US companies trading with China.

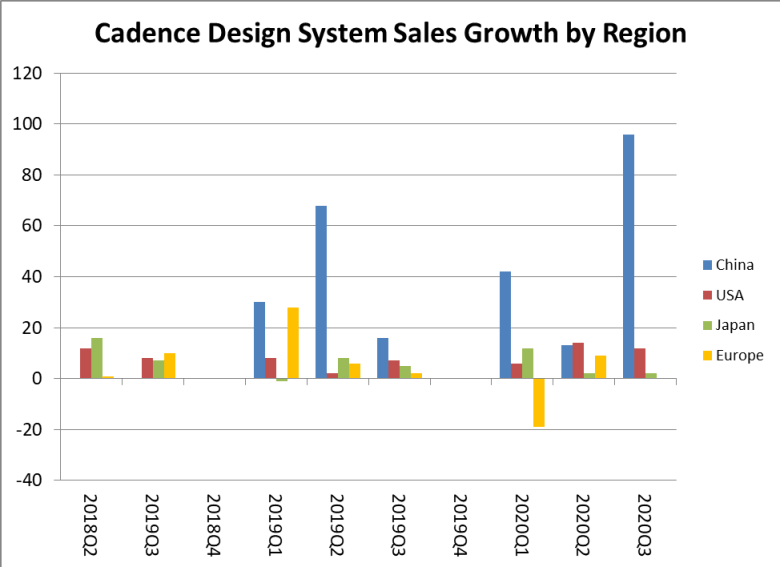

The trouble is that China’s market for semiconductor technology is growing so fast that American firms fear for their long-term viability if they are not involved. The Trump Administration imposed controls on the export of key semiconductor technology six months ago, but American chip design companies’ China sales are booming. Cadence Design Systems, one of America’s top two makers of design software, reports a near-doubling of China sales during the third quarter – after the controls went into effect. Meanwhile, America’s top design firms are investing in the Chinese startups that are hiring away some of their best talent, in order to keep a foot in the door of the Chinese market if they are prevented from selling directly.

Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Rep. Michael McCaul (R-TX) complained Dec. 22 that the new controls announced on SMIC, China’s largest chip fabricator, have a big loophole: The new rules apply only to equipment that is “uniquely” required to produce the most advanced logic chips, with a transistor gate width of 10 nanometers or below. But there’s no clear definition of what “unique” means, so “the Department of Commerce seems to be allowing SMIC access to nearly all semiconductor manufacturing equipment – undercutting the effectiveness of its nominal intent.”

The two Republicans added, “In effect, SMIC will not face serious restrictions, because very few tools are “uniquely capable” of producing a certain chip size. Indeed, SMIC publicly stated that its designation has no material adverse effect on the company’s short-term operations.”

They’re right, but they miss the big picture. SMIC is a minor factor in the world semiconductor market and in China itself, while a myriad of other firms – including telecom giant Huawei – are building chip fabrication lines without restricted US equipment.

According to Dr Handel Jones, CEO of the semiconductor consultancy International Business Services, “SMIC has under 5% of the foundry market and under 2% of the mid-performance foundry market, and 0% of the advanced foundry market. Targeting SMIC can have some longer term implications for China wafer supply but the short-term impact is very low. If semiconductors are so important, the US should strengthen its capabilities rather than try and slow down China. Revenues of SMIC will be $3.9 billion in 2020, compared to revenues of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation of $46 billion. SMIC does not have any special technology and targeting SMIC will provide minimal net benefits to the US. It seems that a number of people in Washington consider that some actions are better than nothing , but reality is that the net impact is negative for the US.”

Meanwhile, Chinese firms are poaching engineers en masse. from Taiwanese foundries and American chip software firms.

Chinese fabrication plants can use a combination of Chinese, South Korean, Japanese and European fabrication equipment to produce less-efficient chips with a gateway width above the 3 to 7 nanometer chips that power high-end cell phones. Used American equipment as well as Extreme Ultraviolet lithography machines from Holland’s ASML, the world’s only provider of the highest-end etching equipment, are available on the secondary market.

Another prospective bottleneck for Chinese chip independence is the design and testing software that the whole semiconductor industry uses to create and verify chip architecture. Two American firms, Synosys and Cadence, dominate the field, and the Commerce Department last August banned Huawei from acquiring their software.

Nonetheless – or rather because of the Commerce Department ban – sales of US software design firms to China exploded during 2020. Cadence, one of the two top US firms, showed a nearly 100% gain in sales to China during the third quarter. Synosys, the other key player, does not break down its sales by country, although press statements earlier in 2020 indicate a brisk growth in China sales.

Everyone but Huawei is buying chip design software, and engineers who used to work at Huawei’s chip design subsidiary HiSilicon now work for startups, many funded by Chinese local government entities. If their designs find their way into Huawei products, that is a matter of intellectual property transfer among Chinese firms, and not subject to US restrictions.

According to some analyst projections, China’s market for electronic design automation (EDA) tools will grow at a 12% compound annual rate during the next seven years, twice as fast as the rest of the world. China’s EDA market will reach $3.9 billion by 2027, compared to a present US market of $2.8 billion. Companies like Cadence and Synopsys can’t maintain their leading position if they are excluded from the the world’s fastest growing (and soon biggest) market for their products.

That is the “parochial commercial interest” to which Rubio and McCaul referred. When China hawks in the Trump Administration first proposed a ban on Chinese purchases of US semiconductor technology a year ago, the Department of Defense objected, warning that the damage to the revenues of American equipment and software providers would stifle their research and development spending, threatening national security. President Trump initially sided with the Pentagon against the Commerce Department, but switched his position after he blamed China for the Covid-19 epidemic in March.

Top executives of Synopsis and Cadence quit last year to start up EDA firms, including X-Epic, Shanghai Hejian, and Amedac. A former top manager at Synopsys China who earlier worked for cadence, Wang Libin, founded X-Epic in March 2020, at precisely the moment when the Trump Administration wheeled out restrictions on sales of US semiconductor technology to Huawei. Dr Wang hired other top engineers from American EDA firms. Two months later another Synopsys engineer founded Shanghai Hejian with funding from the Shanghai municipal government investment fund as well as Chinese venture capitalists.

Another startup headed by a top Synopsys engineer, Amedac, opened its doors in September 2019. In this case Synopsys took a 20% stake in the firm, in partnership with China’s Academy of Sciences. As China reduces its dependence on software tools subject to control by the US government, Synopsys’ stake in Amedac is an insurance policy against its eventual loss of market share.

A number of Western commentators warn that Chinese’s ascent up the learning curve of chip design and fabrication will not be easy, and that it may take years to lift Chinese capacities up to American levels. But a senior executive at a Chinese semiconductor firm commented, “These people don’t understand China. In America everyone thinks in terms of efficiency, and efficiency means return on equity and a rising price. The Chinese don’t care about that when national security is involved. If they have to, they’ll put 10,000 engineers on a problem and work day and night until they solve it.”

The ban on US exports of high-end chips to Huawei hasn’t slowed the buildout of China’s 5G network, but it has added to the cost. As Frank Chen reported in Asia Times Dec. 2, Huawei has installed locally-made chips in its 5G ground stations, rather than the more efficient chips formerly fabricated for Huawei in Taiwan. The chips have the same functionality, but electricity usage is substantially higher.

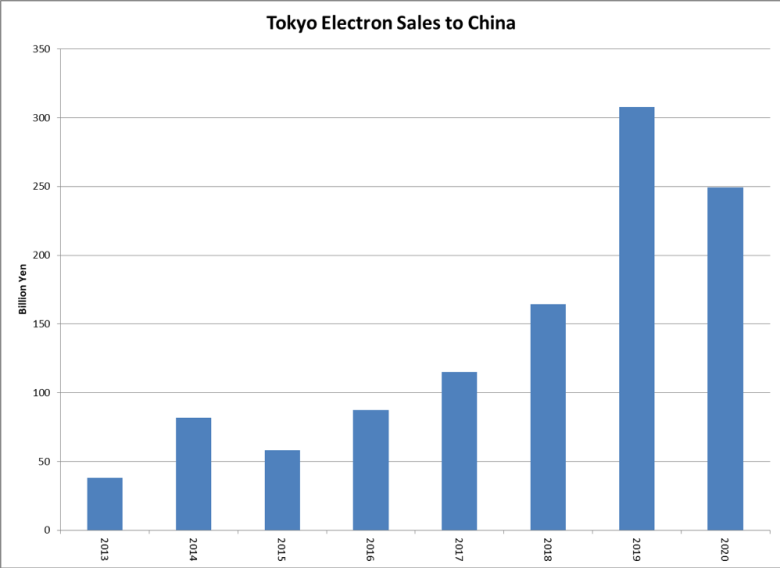

China also has access to semiconductor fabricating equipment outside the United States, although firms like Applied Materials and LAM still dominate some segments of the complex, variegated machinery market. China sales at Tokyo Election, number three in the semiconductor equipment market by some rankings, doubled between 2018 and 2019. The US may put pressure on Tokyo Electron to limit equipment sales to China, as it did in the case of Holland’s ASML, but Japan is less likely to accept American dictates on its China trade after the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership trade pact earlier this year.

Comments are closed.