How Activist Teachers Recruit Kids Leaked Documents and Audio from the California Teachers Association Conference Reveal Efforts to Subvert Parents on Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Abigail Shrier

https://abigailshrier.substack.com/p/how-activist-teachers-recruit-kids

Incensed parents now make news almost daily, objecting to radical material taught in their children’s public schools. But little insight has been provided into the mindset and tactics of activist teachers themselves. That may now be changing, thanks to leaked audio from a meeting of California’s largest teacher’s union.

Last month, the California Teachers Association (CTA) held a conference advising teachers on best practices for subverting parents, conservative communities and school principals on issues of gender identity and sexual orientation. Speakers went so far as to tout their surveillance of students’ Google searches, internet activity, and hallway conversations in order to target sixth graders for personal invitations to LGBTQ clubs, while actively concealing these clubs’ membership rolls from participants’ parents.

Documents and audio files recently sent to me, and authenticated by three conference participants, permitted a rare insight into the CTA’s sold-out event in Palm Springs, held from October 29-31, 2021. The “2021 LGBTQ+ Issues Conference, Beyond the Binary: Identity & Imagining Possibilities,” provided best practices workshops that encouraged teachers to “have the courage to create a safe environment that fosters bravery to explore sexual orientation, gender identity and expression,” according to the precis of a talk given by fifth grade teacher, C. Scott Miller

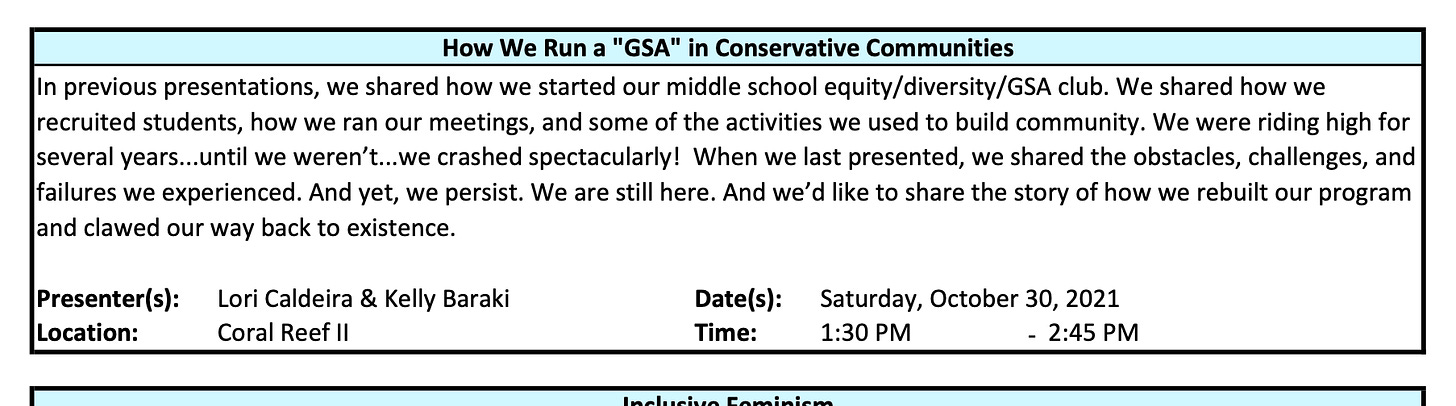

“How We Run a ‘GSA’ in Conservative Communities”

Several of the workshops advised teachers on the creation of middle school LGBTQ clubs (commonly known as “Gay-Straight Alliance” clubs or “GSA”). One workshop—“Queering in the Middle”—focused “on what practices have worked for successful middle school GSAs and children at this age developmentally.”

But what makes for a successful LGBTQ middle school club? What to do about meddlesome parents who don’t want their middle schoolers participating in such a club? What if parents ask a club leader—point blank—if their child is a member?

“Because we are not official—we have no club rosters, we keep no records,” Buena Vista Middle School teacher and LGBTQ-club leader, Lori Caldeira, states on an audio clip sent to me by a conference attendee. “In fact, sometimes we don’t really want to keep records because if parents get upset that their kids are coming? We’re like, ‘Yeah, I don’t know. Maybe they came?’ You know, we would never want a kid to get in trouble for attending if their parents are upset.”

The advice to those who run middle school LGBTQ clubs is: keep no records, so you can plead ignorance of the membership with the members’ parents. In fact, middle school teacher Kelly Baraki can be heard in the same session describing having named her club “the Equity Club,” and then, “You be You,” rather than the more ubiquitous “GSA.”

Caldeira and Baraki – both middle school teachers – led a workshop titled: “How we run a ‘GSA’ in Conservative Communities.” The audio recording of their lecture was sent to me by a conference attendee. In that address, the speakers describe the challenges for activist teachers working in the context of a politically mixed community in Central California with many conservative parents.

“We miss them when they don’t join us.”

The teacher leaders of the LGBTQ club apparently faced a constant problem: How to keep the middle school kids coming back to their group? “We have LGBTQ kids who come to us, and they come and spend a year with us and they get all the love and the affirmation that they need,” Caldeira can be heard to say. “And we give them tools to be powerful and brave and bold” but then they “go hang with their friends at lunch. And they do their things. And we love them for that, but we miss them when they don’t join us. So we saw our membership numbers start to decline.”

“We totally stalked what they were doing on Google…”

Middle school kids, apparently, did not have endless interest in sitting around with their teachers during lunch discussing their sexual orientations and gender identities. “So we started to brainstorm at the end of the 2020 school year, what are we going to do? We got to see some kids in-person at the end of last year, not many but a few. So we started to try and identify kids. When we were doing our virtual learning – we totally stalked what they were doing on Google, when they weren’t doing school work. One of them was googling ‘Trans Day of Visibility.’ And we’re like, ‘Check.’ We’re going to invite that kid when we get back on campus. Whenever they follow the Google Doodle links or whatever, right, we make note of those kids and the things that they bring up with each other in chats or email or whatever,” Baraki can be heard to say. Beyond electronic surveillance of kids’ internet use, “we use our observations of kids in the classroom—conversations that we hear—to personally invite students. Because that’s really the way we kinda get the bodies in the door. Right? They need sort of a little bit of an invitation,” Baraki says in the clip.

For those paying attention, the educators who guide California teachers in the creation of middle school LGBTQ clubs asserted the following: they struggle to maintain student participation in the clubs; many parents oppose the clubs; teachers surveil students electronically to ferret out students who might be interested, after which the identified student is recruited to the club via a personal invitation.

“I’m the teacher who runs our morning announcements,” Caldeira can be heard to volunteer. “That’s another type of strategy I can give you. I’m the one who controls the messaging. Everybody says, ‘Oh, Ms. Caldeira, you’re so sweet, you volunteered to do that.’ Of course I’m so sweet that I volunteered to do that. Because then I control the information that goes home. And for the first time, this year, students have been allowed to put openly LGBT content into our morning announcement slides.”

Caldeira gushes about the student “team” she assembled to help with the announcements: “Three of the kids on the team, two of them are non-binary, and the other one is just very fluid in every way—she’s fabulous. So it’s actually a nice group. And the principal, she may flinch, but she [flinches] privately.”

But if students aren’t especially interested in attending an LGBTQ club, if the leaders have trouble maintaining membership, if parents oppose them and schools, as Caldeira complains, often fail to support them—why on earth are teachers pushing them? “For those of you that are running or are thinking of running your own GSA or GSA-type club, always remember that youth are the drivers of change,” Caldeira offers. If you want to bring a new world into existence, it seems—a good place to start is with other people’s kids.

“Next year, we’re going to do just a little mind-trick on our sixth graders.”

On the audio recording, Baraki and Caldeira explain that they give an anti-bullying school presentation every year. “Let me assure you that the presentation that we gave was 100 percent age appropriate. Literally, definitions: ‘If someone is gay, it is a man who is attracted to another man.’ Right? ‘If somebody is a lesbian, it is a female attracted to another female.’ Literally, gave them definitions. We also covered religious differences, race, cultural backgrounds, family status poverty—everything that is listed in the Parents’ Rights handbook, we covered. That is not what kids went home and told their parents, though,” Caldeira said.

There was parent backlash; Caldeira and Baraki learned from the experience: “Next year, we’re going to do just a little mind-trick on our sixth graders. They were last to go through this presentation and the gender stuff was the last thing we talked about. So next year, they’ll be going first with this presentation and the gender stuff will be the first thing they are about. Hopefully to mitigate, you know, these kind of responses, right?” Baraki can be heard telling the teacher audience. Parents who oppose this material being taught to their sixth graders will find that their objections arrive too late.

A conference attendee told me that Baraki then directed the participants’ attention to a parent email objecting to the presentation. The parent had written that she had not intended to have a conversation with her middle schooler about sexual orientation and gender identity, but the school presentation forced her hand. Baraki mocked the parent to her audience: “I know, so sad, right? Sorry for you, you had to do something hard! Honestly, your twelve-year-old probably knew all that, right?”

One parent objected so strenuously that the principal “invited them to take their child to a private school that more aligns with them,” Caldeira can be heard to say. “So that was a win, right? We count that as a win.” Then, Caldeira added: “Plus, I hate to say this, but thank you CTA—but I have tenure! You can’t fire me for running a GSA. And so, you can be mad, but you can’t fire me for it. CTA has made it very clear that they are devoted to human rights and equity. They provide us with these sources, these resources and tools.”

Despite the use of these sundry tactics, Caldeira insists to her audience of educators: “You should know, we’ve also acted with great integrity in the past several years that we have run [a GSA]. We never crossed a line,” she says. “We’ve wanted to, but we never have.”

I have no reason to believe that these activist educators are part of the gay or transgender communities themselves. For decades, gay Americans lived under the shadow of a vicious calumny that—if granted full inclusion in society—they would ‘recruit’ children. This was, and remains, a lie—one that was used to justify bigotry, even violence. But taking advantage of Americans’ current desire for LGBTQ inclusiveness, California’s largest teachers’ union seems, perversely, to have perceived the opportunity to coach teachers in student-recruiting tactics.

“What happens in this room, stays in this room.”

Caldeira is an award-winning teacher and the leader of her school’s Equity Club. She has shared her views publicly before. In a podcast interview on November 5, 2020, Caldeira said much the same: “And so our Equity Club, we have dealt with issues of race, we have dealt with issues of different religious belief systems. We deal a lot with sexual orientation and gender identity,” she explains. “As middle schoolers, that’s the age where they are asserting their identity and defining themselves as a separate entity from their parents. And so they are looking, I think, for some guidance on: Is this OK? Can I do this? What does this mean? And so we talk about that.”

As Caldeira said on that podcast, that topics for her Equity Club are selected by her middle schoolers: “So the kids come, they have something on their mind they want to talk about it and then we have some structures in place for how to have those kind of complicated conversations. And you know, they include those group norms about respect: What happens in this room, stays in this room.” That might lead parents to an obvious follow-up: Does a middle school child talking to her parents about the content of these meetings constitute a violation of the “group norms?”

I reached out to Spreckels Union School District—at which both Caldeira and Baraki teach—for comment. Neither Superintendent Eric Tarallo nor Buena Vista Middle School Principal Katelyn Pagaran nor Baraki or Caldeira replied to my requests for comment.

Comments are closed.