Pearl Harbor 80th anniversary brings memories, tributes – and a lesson Lesson of Pearl Harbor is to be vigilant not only for the unexpected but also the expected By Walter R. Borneman

“As we honor those who gave their all 80 years ago, the need to adapt before the next attack remains the greatest lesson of Pearl Harbor. The aircraft carriers and air power that changed warfare in 1941 are still key components of American military might, but our enemies employ other weapons. Terrorism on unprecedented levels brought about the devastation of 9/11. Digital attacks on infrastructure and networks are evidence that keyboards more so than aircraft carriers are already fighting the next wars. “

The attack on the United States fleet at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, 80 years ago today, remains one of the most traumatic events in American history. The date is a generational landmark comparable to the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the horrors of Sept. 11. America changed overnight.

Eighty years later, the Pearl Harbor tragedy is still highly personal. It continues to touch the families of the 2,403 servicemen who lost their lives and the many more who survived that Sunday morning. At a national level, the legacy of a country first surprised but then remarkably united still resounds.

Many at Pearl Harbor found themselves on the front lines not out of patriotic pride or personal desire to see the world, but out of economic necessity. They were children of the Depression and the $5 or $10 most sent home out of monthly incomes of $36 for a seaman recruit helped to feed younger siblings. Less concerned with national strategies, their personal goals were a few dollars in their pockets, more letters from girlfriends and living to see another sunrise.

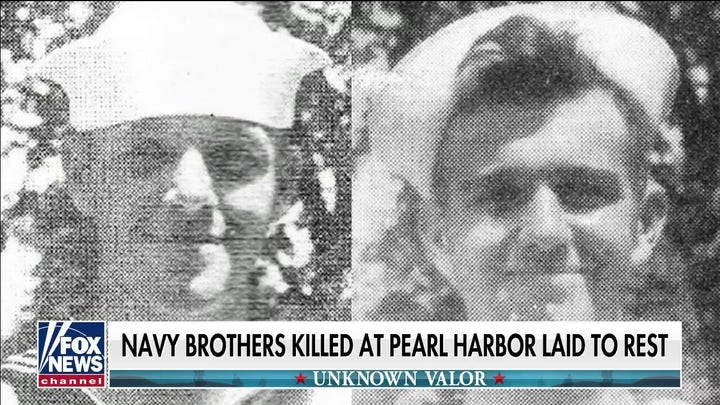

Of a crew of 1,500 on the battleship Arizona, 1,177 sailors and Marines, including a rear admiral and the newest recruit, perished. Among the 78 men with a brother aboard, only 15 survived the attack – a staggering 80% casualty rate. The lucky ones lived with enormous personal grief and sometimes, profound survivor’s guilt.

Only two men from the Arizona’s crew who were at Pearl Harbor are still alive. Louis Conter, who was standing watch on the quarterdeck, eventually retired as a lieutenant commander after 23 years of service. Ken Potts, a coxswain in a small boat shuttling supplies across the harbor, left the Navy in 1945 as a petty officer. Both men celebrated their 100th birthdays this past year. They and the handful of remaining survivors from that day are national treasures.

Despite the surprise attack, many of the sailors, soldiers, airmen and Marines stationed throughout the Pacific in 1941 had expected a war to break out sometime, somewhere. Bud Heidt, a sailor on the Arizona, wrote his girlfriend days before the attack that they shouldn’t waste a minute when together because “you know as well as I do that we may be at war any day now.” If that was the attitude among the rank and file, should their superiors have been better prepared?

On two prior occasions, aircraft from American carriers staged mock attacks on the Hawaiian Islands. Near sunrise on Feb. 7, 1932, Navy planes caught Army Air Corps bases by surprise. In the after-action critique, the Army protested that the attack at daybreak on a Sunday morning, while permitted under war game rules, was a dirty trick.

Six years later, Rear Adm. Ernest J. King led an exercise from the carrier Saratoga with similar results. In the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor defeat, the aggressive King was given command of all U.S. Navy forces and ordered to wage a two-ocean global war. His watchword became “expect the unexpected,” but, as he had shown, he knew one should also prepare for the expected.

As we honor those who gave their all 80 years ago, the need to adapt before the next attack remains the greatest lesson of Pearl Harbor. The aircraft carriers and air power that changed warfare in 1941 are still key components of American military might, but our enemies employ other weapons. Terrorism on unprecedented levels brought about the devastation of 9/11. Digital attacks on infrastructure and networks are evidence that keyboards more so than aircraft carriers are already fighting the next wars.

There will be more Pearl Harbors.

After losing two sons aboard the battleship Arizona, Clara May Morse of Denver wrote of “my Pearl Harbor.” Others would have their own Pearl Harbors, she confided to her diary. “I feel for them very much because I know.”

Clara Morse was thinking of individual loss, but the lesson of Pearl Harbor is to be vigilant not only for the unexpected but also the expected. Preparing for that is a proper tribute to those we remember.

Comments are closed.