When the Crime Wave Hits Your Family Our nanny’s living room in Oakland was sprayed with bullets. It didn’t even make the local news. Leighton Woodhouse

https://bariweiss.substack.com/p/when-the-crime-wave-hits-your-family

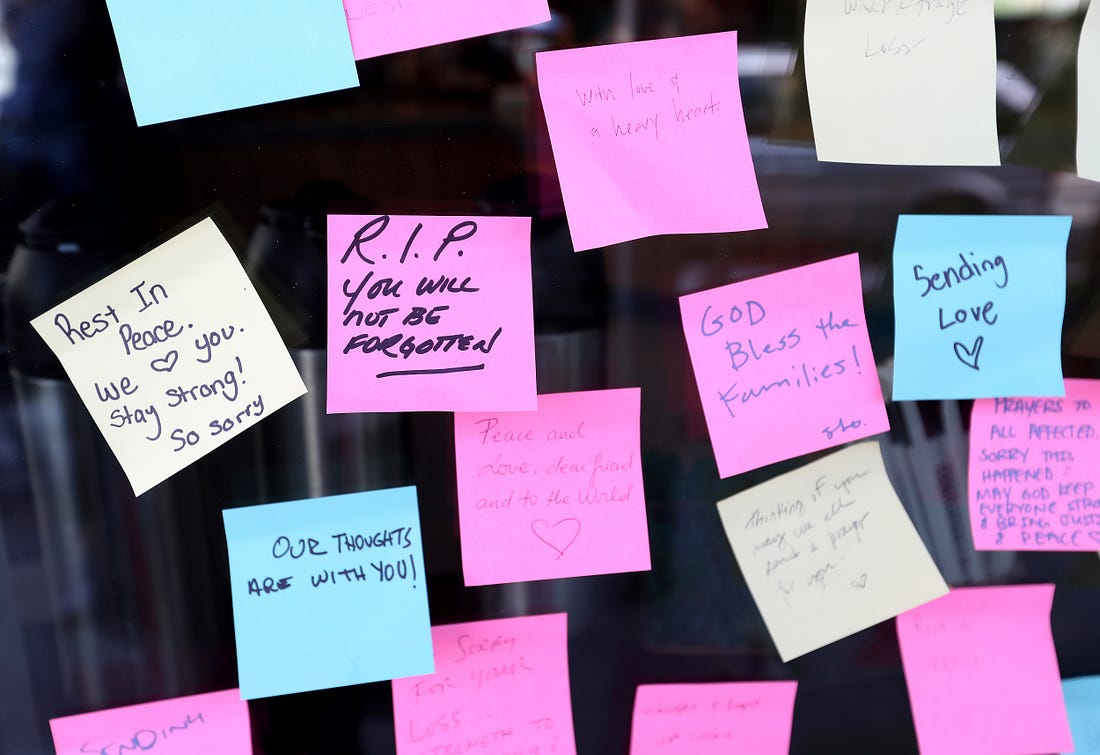

My wife and I are scrambling to find daycare for our 16-month-old son. We’ve had a “nanny share” up until now, which means we and another couple employ a nanny for both couples’ kids and split the cost. Our nanny is wonderful, and she lives just a few blocks from us. But a few weeks ago, someone walked up her street spraying bullets into random houses. One of the bullets found its way into her living room, as she and her family ducked for cover. At that moment, she and her husband decided they were moving their family out of Oakland.

The shooting didn’t even make the local news. Apparently, in the Bay Area right now, you can walk up a residential street firing your gun into houses, and you still won’t be able to compete for attention with all of the other sensational crimes.

Perhaps you’ve heard about some of them or seen the videos.

Shoplifters casually walk into Walgreens stores in San Francisco filling garbage bags full of merchandise. They’ve spat on, bitten, assaulted, and thrown bottles of urine at employees.

The flashmob-style “smash and grab” robberies that originated here—in places like Union Square in San Francisco and the shopping plaza in affluent Walnut Creek—have now spread across the country.

Asian seniors are brazenly assaulted in the street; one octogenarian was body slammed to death. This week, an Afghan refugee—a father of three who had worked as a translator for the U.S. army—was shot dead near a playground in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood.

And now freeway shootings are a thing. A few weeks ago, at nine in the morning, a 29-year-old mom on her way from Oakland to San Francisco for a job interview with her fiancé and two kids was randomly shot and killed in her SUV at the Bay Bridge toll plaza. In an interview, the victim’s mother recalled being heartbroken after hearing the story of an earlier crime, in which Jasper Wu, a two year-old who was sleeping in his car seat, was shot and killed by a stray bullet fired from another car driving in the opposite direction. It was not even two weeks later when she lost her own daughter the same way.

I recently finished reading “San Fransicko,” by Michael Shellenberger. I recommend it. The subtitle is provocative: “Why Progressives Ruin Cities.” But, as Shellenberger explains, he does not mean to imply that progressives always ruin the cities they govern. He’s just interested in the specific phenomenon of when progressives do ruin cities, and explaining why that happens.

And progressives—I count myself as one of them—do ruin cities. Or, at least, they put in place policies that cause profound harm to the people living in them. An obvious case-in-point is the call to defund the police. It’s a slogan that fits nicely on a bumper sticker, but what are its consequences in practice?

After a summer of protests against police violence, progressive cities like New York, Seattle, Minneapolis, Austin, and Denver cut their police budgets in 2020 even during a national surge in violent crime. That surge has only continued into 2021, in some places by wide margins. The wave of murders in American cities has provoked political backlashes to the cuts, which have forced some local governments to backtrack from their defund agenda.

But that hasn’t stopped demoralized departments from bleeding officers through attrition. Austin, for example, which voted in 2020 to cut its police budget by a third before restoring most of it this year, is losing 15 to 22 officers per month. Its homicide rate is up 88 percent over last year, blowing past a previous homicide record that was set nearly four decades ago.

How do activists justify hobbling cities’ ability to respond to the crime wave by gutting their police forces? Here’s Cat Brooks, perhaps Oakland’s most prominent police abolitionist, in The Guardian: “The goal is to interrupt and respond to state violence,” she explained. “We’re good at responding but the only way you get to interruption is to reduce the number of interactions with police.”

That’s true: If you have fewer interactions between police and civilians, you’ll likely have fewer acts of violence perpetrated on civilians by police. The obvious problem with this “solution,” though, is that you’ll also have more crime.

This isn’t just deduction. It’s been measured. Harvard economist Roland Fryer looked at what happens in cities after a high-profile police killing of a civilian that results in an investigation of the department. The answer is that police do exactly what Cat Brooks wants: They stop interacting with civilians.

That could be because officers become excessively vigilant about not becoming the next suspect in a police shooting. Or it could be that they’re cynically demonstrating to the public how necessary they are. Or it could be a bit of both. It doesn’t really matter. The point is that we can see what happens when cops stop interacting with the public.

I have seen the unraveling over the past year in my own neighborhood. In October, about three blocks from my house, a neighbor was shot and killed in a home invasion. About a mile south in the same month, a 15-year-old girl was shot to death in an act of road rage. And just a few weeks ago, a little more than a half-mile west of me, another teenager was fatally shot.

But don’t take my word for it. Look at what happened in Chicago, in 2014, after the murder of Laquan McDonald at the hands of the police. Police-civilian interactions dropped by 80 percent in the three weeks following the release of the video showing the killing. For a full two years after the murder, the homicide rate in Chicago increased. Fryer estimates that about 180 murders occurred in Chicago because of the reduced number of police-civilian interactions that followed McDonald’s murder. Nationally, Fryer counts 893 murders and almost 13,500 felonies that occurred because of reduced police-civilian interactions in five American cities.

Defund advocates often claim that police don’t actually prevent crimes, that they only bust the perpetrators after the fact. But that’s untrue. Police presence deters crime. Arresting career criminals takes them out of circulation. And, most important, effective policing bolsters a community’s faith in government-administered justice.

In her brilliant book “Ghettoside,” journalist Jill Leovy shows what happens when the police clearance rate—the rate at which the police close cases—is abysmally low: People can literally get away with murder. Under those conditions, the friends and relatives of murder victims assume, quite rationally, that the criminal justice system will not provide them with justice. They can live with their loved ones’ murderers enjoying impunity for their crimes, or take justice into their own hands—triggering a new cycle of violence.

Defund advocates dismiss these arguments—not because they can refute them with evidence, but because they’re blinded by ideology. Their hyper-focus on police misconduct seems to have made it impossible for them to see, let alone acknowledge, the benefits of an effective police force. Even in the absence of a viable alternative, they demand that existing law enforcement structures be torn down. They claim that, by taking money from police and putting it toward social programs, they can eliminate the need for heavy-handed policing in the first place. But the social programs are an afterthought. What matters most to these activists is tearing down the cops, not building up the tattered neighborhoods those cops are charged with protecting.

In “San Fransicko,” Shellenberger traces what happened when that same approach was brought to another perceived injustice: insane asylums. In the name of liberating the mentally ill from their imprisonment in mental hospitals (which were truly horrific places), progressives of an earlier era fixated on tearing down these evil institutions, but not on building up something with which to replace them (contrary to popular belief, in California, this effort was underway well before Ronald Reagan became governor, and it was a progressive initiative). The goal of safeguarding the civil liberties of the mentally ill was a laudable one. But without an alternative to those institutions, the outcome for the afflicted was, if anything, worse.

We live in the aftermath of the progressives’ triumph over institutionalization, and it looks like San Francisco’s Tenderloin District or L.A.’s Skid Row. Today, with few exceptions, there is no more involuntary treatment for serious mental disease or drug addiction. But nor is there a humane alternative. There is only jail or the streets.

The same thing is now happening with criminal justice. Progressives today are passionate about dismantling the status quo, but have offered little in terms of a viable alternative. It’s a posture Shellenberger calls “left libertarianism,” and it assumes that those kinder, better, more forward-looking criminal justice systems will spontaneously emerge. The past year has given us plenty of evidence to reveal that idea as the wishful thinking it is. Remember progressives’ utopian experiment with CHAZ/CHOP, the Seattle neighborhood taken over by activists in June 2020? Once the area had been “liberated” from police, it saw a five-fold increase in crime from the same period in 2019, including rape, murder, robbery, and assault. “The area has increasingly attracted more individuals bent on division and violence,” the mayor said in a statement, “and it is risking the lives of individuals.”

The push to defund the police has typically been more popular in higher income areas of progressive cities like Oakland—areas where crime and violence are more of an abstraction than a daily reality. Not surprisingly, the two Oakland city council members who last summer voted against reducing the mayor’s proposed budget for the police represent the poorest, most dangerous neighborhoods in the city. But now, in Oakland and San Francisco, the crime wave is hitting the affluent neighborhoods, too, as well as the spaces that everyone shares—like the freeways and the Bay Bridge toll plaza.

As the surge in violence has become less theoretical to white, middle class residents, Oakland’s mayor has been afforded the political space to push to restore the funds that were cut from the police budget. Suddenly, the nihilistic ideology of the progressive activist class has lost the cachet it was imbued with during the hot summer of 2020.

I grew up in the East Bay in the 1980s and ’90s, another era of surging crime. I remember the low-level ambient fear that hovered over you any time you took the BART train or walked around downtown at night. There was a lot of fanning of the flames back then, everywhere in the country—we used to hear a lot about “crack babies” and “super predators”—and that kind of hyperbole could transform that low-level fear into paranoia. Today, there’s the opposite: a sensational exaggeration of the threat of the police, and a stubborn denial of the reality of rising street crime.

I understand the reflex: nobody wants to return to the draconian politics of that earlier era, which fueled racism and mass incarceration. But street crimes almost always target poor people. We do them no service by pretending that the police are the only force capable of making them victims.

Comments are closed.