Alvin Bragg, the Prosecutor Who Won’t Prosecute By Barry Latzer

You may have the impression that criminal-justice progressives took a big hit in the last election. That’s because the media played up the defeat of the Minneapolis measure to replace that city’s police with a new public-safety department. But while that was a significant victory over the anti-police movement, it wasn’t the only criminal-justice issue on ballots. Nationwide, voting results were mixed. In Austin, Texas, for instance, a measure to undo a slashing of the police-department budget by one-third failed. And more ominously, progressive prosecutors, such as Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner, continue to win elections. There are leftist district attorneys in Chicago, Boston, Houston, and St. Louis. And don’t forget San Francisco, where Chesa Boudin presides over shoplifter heaven (and faces a recall election in June over his policies). Now we have to add to the list Manhattan, where Alvin Bragg just swept to victory.

To Bragg’s credit, he laid out in detail his policy plans, a reflection of previous jobs in which he gained familiarity with the legal issues surrounding criminal cases. But those plans are so driven by ideology and so fixated on reducing incarceration that one can only hope he does not (or cannot) carry them out.

To prove my case, I will explore in depth two policy issues that Bragg discussed at length in his campaign literature. They are issues that every district attorney must deal with: pretrial release (the processing of a case after arrest and before final adjudication) and the treatment of low-level offenses (in New York, misdemeanors and violations).

Releasing Criminals

Pretrial release is the handling of a case shortly after arrest and before final adjudication (by trial or, more likely, a plea). In most of the United States it is a settled matter that dangerous arrestees can be held in jail before adjudication. Nearly every state empowers judges to detain defendants in the interest of public safety even though their cases haven’t yet been adjudicated. The Supreme Court greenlighted this years ago (United States v. Salerno, 1987), differentiating punishment (permitted only after adjudication) from administrative confinement.

New York State is the outlier, limiting judges to consideration of flight risk and forbidding them to take the arrestee’s dangerousness into account. Compounding the problem, New York’s recent bail-reform law requires release in the absence of a demonstrated risk of flight. It also prohibits either bail or jail in most cases even with proof that the defendant is unlikely ever to enter a courtroom voluntarily.

Since the overwhelming majority of states allow bail or jail on public-safety grounds, the hot national debate is over the use of objective measures, sometimes fashioned into algorithms, to determine the risk of release. New Jersey, for example, recently adopted such an algorithm, but New York is out of the loop, willfully blinding itself to the public dangers of release.

DA Bragg is content with New York’s reforms and seems bent on making things even worse. He opposes giving New York judges (and prosecutors) the discretion to determine a defendant’s dangerousness when deciding whether to release him. Why? He thinks dangerousness determinations are racist. “I have no confidence,” he says, that “there is any race-neutral way to predict who is dangerous at such an early stage in the case.”

This is preposterous. Suppose there is compelling evidence that a defendant has committed a violent crime and that he has, in addition, a prior conviction for a crime of violence. Assume as well that he has a history of failing to appear in court. Under such circumstances, most people would conclude that the judge certainly should have the authority to send the defendant to jail, or at least to impose bail. It would create a real danger to the public to release such a person willy-nilly.

An algorithm or even a simple list of the considerations described above is obviously race-neutral. Whether a crime is violent and whether the defendant has priors and a history of no-shows are objective, nonracial considerations. Whether the evidence is compelling, even though not yet tested at trial, is also unrelated to race. (An example would be testimony from a victim who knows or is related to the defendant.) A prediction that such a defendant would be a public threat if released — and such a case is not uncommon — is entirely race-neutral.

But Bragg buys the woke thinking that disparate racial impact is the same as race bias. In other words, if the criteria for bail or jail, even if totally race-neutral, put a disproportionate number of African Americans in jail, then the criteria must be faulty. This reasoning is profoundly flawed. It ignores the realities that the proportion of criminal activity involving blacks is significantly higher than the proportions involving whites or Hispanics, while blacks compose a lower share of the population. For instance, just before the pandemic, in 2019, African Americans accounted for 55 percent of felony arrests in Manhattan, where they were only 12 percent of the population. Whites, who were 47 percent of the population, accounted for only 10 percent of the felony arrests; Latinos, 26 percent of the population, were 35 percent of felony arrestees. Consequently, race-neutral criteria are bound to impact blacks more often — unless Bragg finds a way to establish racial quotas for prosecution.

If Bragg’s office encourages the release of dangerous defendants because they are black, then it will add to the crime and disorder in communities of color, which is where such defendants are most likely to reoffend. Instead of obsessing over the racial makeup of dangerous defendants, DA Bragg should ask himself whether minority communities deserve the full protection of the law-enforcement system.

Manhattan’s new DA goes beyond even New York’s flawed new bail law, promising to establish a presumption of release: “My office will recommend non-incarceration for every case except those with charges of homicide or the death of a victim, [or] a class B violent felony in which a deadly weapon causes serious physical injury, or [certain] felony sex offenses.”

Note that Bragg will recommend against incarceration in every single pretrial case, with a limited list of exceptions. His list is totally inadequate. There are numerous violent crimes that do not involve death, or a serious injury from a deadly weapon, or a felony sex offense, but, for the sake of public safety, warrant incarceration. There should be no presumption of release in such cases. Here are just a few examples: robbery second degree, which involves several robbers working together, or physical injury to the victim, or the display of a gun; assault on a police officer, firefighter, or judge; gang assault second degree, which involves an attack by two or more people and results in serious physical injury, such as that caused by a shooting or stabbing; aggravated vehicular assault, caused by reckless driving either when drunk or with a suspended license; reckless endangerment first degree, which creates a grave risk of death; stalking first degree, which causes physical injury to the victim; and menacing second degree, which places a person in fear of physical injury by displaying a deadly weapon or repeatedly following the victim or repeatedly putting the victim in fear.

How does releasing people arrested for crimes like these help black communities — or any community, for that matter — especially given the high likelihood of repeated crimes?

Low-Level Offenses

DA Bragg promises to dismiss every misdemeanor or divert the case out of the criminal-justice system. Many misdemeanors are worthy of criminal punishment, so his overbroad approach is unwarranted. If Bragg wants to divert these cases to some other quasi-judicial body, that’s fine if there are institutions capable of handling them. But this is little more than a pointless shell game, since, as I’ll show in a moment, the current system is quite lenient.

Bragg claims that there are too many low-level prosecutions, that the punishments for these offenses “are disproportionately harsh,” and that the penalties “fall disproportionately on the backs of people of color.”

Our courts have been clogged with petty offenses for too long. From smoking marijuana to jumping a turnstile, our criminal courts spend far too much time treating minor offenses with the same blunt instruments used to address homicides and other violent crimes. . . . This deluge of low-level prosecutions has disproportionately harmed people of color: over 80% of those charged with misdemeanors and 82% of those charged with non-criminal offenses are people of color.

Too many low-level cases? First, this is for the state legislature to determine, not a single district attorney. If the legislature wants to decriminalize low-level offenses, including the violent misdemeanors I listed above, that’s within their authority. Of course, that won’t ever happen. But a prosecutor’s discretion in handling a particular case or even a particular crime shouldn’t be inflated into the power to cancel entire chunks of the penal law.

Bragg is right about one thing, though: Minor crimes constitute the lion’s share of criminal cases. They were 79 percent of all prosecutions citywide in 2019. So what? Minor crimes always predominate — always have and always will. It would be a very scary city if major felonies were the dominant crimes. We can, of course, debate which behaviors should be decriminalized, weighing the social impact of various acts, the effectiveness of noncriminal sanctions, and the effect of the punishments on the offender. As the public’s standards change — think adultery, abortion, marijuana possession — we may want to decriminalize additional crimes. But wholesale decriminalization of minor crimes by a prosecutor is an abuse of authority.

Second, Bragg grossly exaggerates the prosecutorial impact of low-level convictions on African Americans. In 2019, there were 20,980 misdemeanors charged in Manhattan, of which 9,770, or 47 percent, of the defendants were black. The citywide percentage is identical: Blacks made up 47 percent of the defendants in misdemeanor cases prosecuted. People of color are not being prosecuted at anywhere near the 80 percent level that Bragg claims.

Nor are the punishments “disproportionately harsh.” When misdemeanor cases citywide were arraigned — that is, brought before a judge for the first time a day or two after arrest — 90 percent of the defendants were released and 10 percent were admitted to bail. And these figures were for 2019, before the 2020 bail reform made release virtually mandatory.

In the next phase of the cases, between arraignment and disposition (meaning the determination of guilt or innocence), 68 percent of the misdemeanor defendants were released. At sentencing, the final step in the adjudication process, very few low-level offenders were incarcerated. Of 21,644 Manhattan misdemeanants sentenced, only 12 percent got jail time beyond their period of pre-sentencing incarceration. A third (34 percent) were sentenced to time already served, and another third (33 percent) were conditionally discharged. Should those discharged defendants violate the conditions of release, Bragg declares, he will simply ignore their contempt for the law. Even if there is “clear evidence that the person willfully violated conditions of release, or if the individual has failed to appear more than once on the current charge,” Bragg will, he says, forbid his assistant DAs to seek bail or jail without supervisory permission.

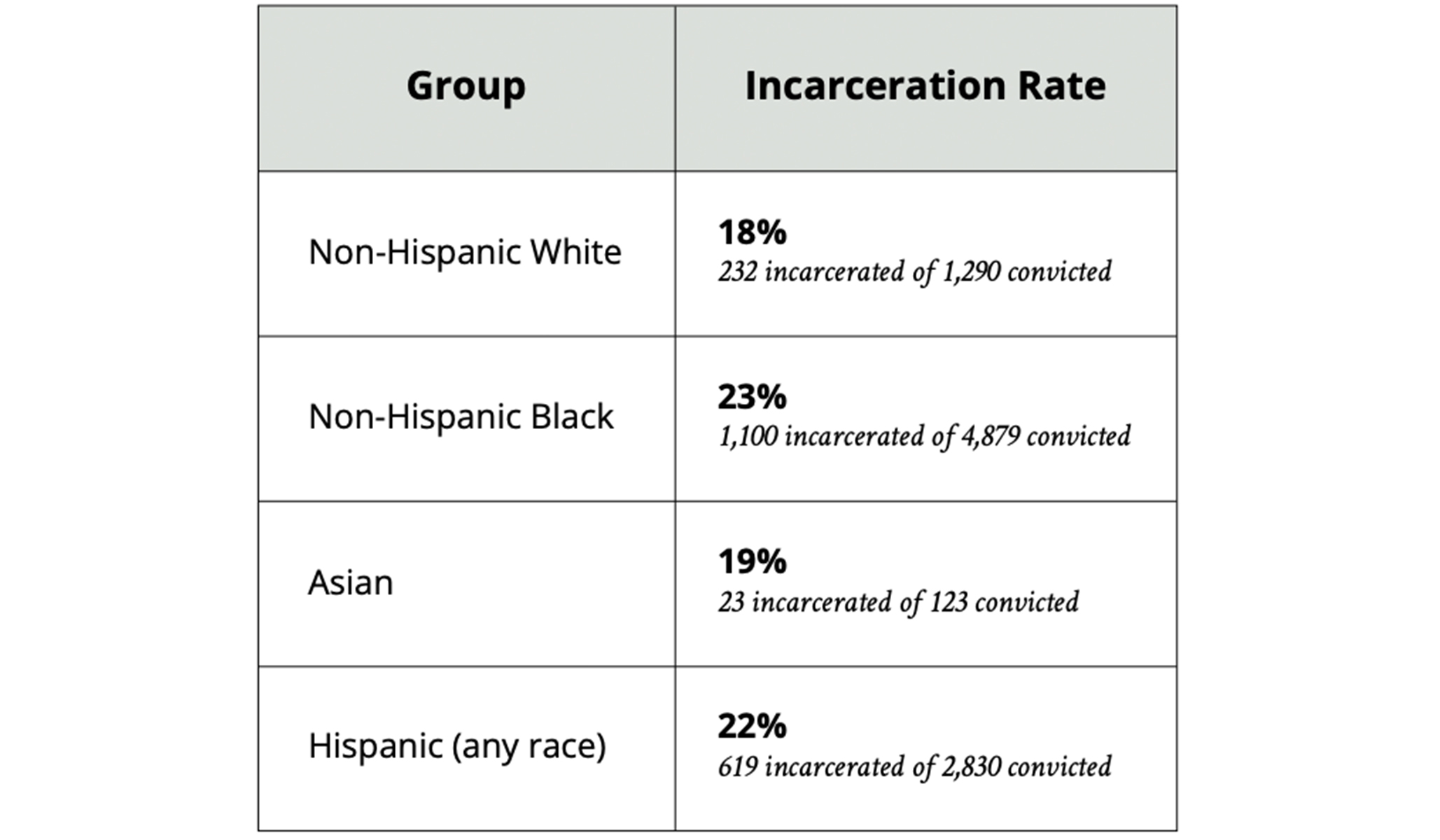

Surely a system that releases 90 percent of misdemeanor defendants within a day or two of arrest and sentences only 12 percent of those convicted to additional jail time is not “disproportionately harsh.” Nor is there much disparity between the incarceration of blacks and other groups. The incarceration rate for African Americans in Manhattan is only slightly above the rate for Hispanics, for instance.

While his racism claim is baseless, the central problem with DA Bragg’s approach is his premise that prosecuting low-level offenses is inherently wrong. Low-level crimes such as excessive noise at night, aggressive panhandling, jumping subway turnstiles, streetwalking prostitution, public use of drugs, loitering in apartment-building hallways, and public urination are offensive to the vast majority of citizens. They undermine neighborhoods by creating anxiety and fear and making streets unsuitable and unsafe for families and children. They attract drug dealers, other serious criminals, and boisterous rowdies. Who would want their kids to play on such streets or walk to school there unaccompanied? These offenses make residents reluctant to go out, walk about, use the parks, or even shop locally. They even make them afraid of their own apartment buildings. In short, they force the law-abiding to surrender public spaces to the lawless.

Low-level offenses are all about public disorder. We’ve seen what widespread disorder can do to our cities, and we don’t want to return to the horrors of the 1970s and ’80s. If disorder blights minority communities more than white neighborhoods, then they deserve and will demand, as they did in the crack-cocaine era, stepped-up enforcement — even if it means that disproportionate numbers of minorities will be prosecuted.

The notion that increased law enforcement is harmful is a deeply troubling position for a prosecutor. Prosecution remains one of the most effective tools we have for coping with misconduct. The public depends on prosecutors to protect the law-abiding by bringing criminals under control, be they petty or serious. Bragg doesn’t get this. He is more concerned with the welfare of the offenders than with that of their victims or of the communities they despoil. But the more lenient he is with offenders, the more they will repeat their crimes as word spreads on the streets that there is no enforcement. (Think about the effects of unenforced shoplifting laws in San Francisco, which has led to gangs boosting goods with impunity, closing down or crippling scores of businesses. Even the city’s leftist mayor, London Breed, declared that “it’s time” for “the reign of criminals who are destroying our city . . . to come to an end.”) Leniency victimizes law-abiding residents, including — and probably especially — those living in communities of color. This is the soft racism of underenforcement.

Progressives are under the illusion that prosecutors are all-powerful and that woke DAs can upend the criminal-justice system. (See, for example, Emily Bazelon’s book Charged.) They are mistaken. Even a district attorney such as Bragg can do only so much. Take low-level offenses. The penalties are so insignificant that it has rightly been said that the arrest and prosecution alone are, in most cases, the real punishments, the only punishments. Of course, if the new district attorney refuses to pursue certain offenses altogether, and the police therefore refuse to arrest, we will see significant change — and it won’t be for the better. Otherwise the police, with their decision to arrest, hold the key card.

The role of the district attorney’s office at sentencing for serious crimes is another example of the limits on prosecutors. Bragg has threatened to undercut the state legislature’s sentencing provisions by systematically recommending sentences at the low end of legislative guidelines — even for some of the most serious criminals. While the prosecutor can recommend a sentence within the guidelines, the judge does not, however, have to accept that recommendation.

In short, the system controls the DA, maybe more than the DA controls the system. Still, New York City has a big crime problem, and the new mayor, Eric Adams, has promised to get it under control. One week into Mayor Adams’s term, after Bragg reaffirmed his leniency policies in a lengthy memo, the new NYPD commissioner, Keechant Sewell, publicly attacked the DA in an email to the entire police force. In the message, which was released to the media, Sewell told her officers she was “very concerned about the implications to your safety as police officers, the safety of the public and justice for the victims.” Bragg and Sewell subsequently met to iron out differences, while Adams declined to criticize the district attorney.

We’ll see if Bragg will back down and adjust his no-incarceration policies. For New York City and Mayor Adams, the stakes could hardly be higher.

Comments are closed.