Condoleezza Rice, Coleman Hughes & More on Black History Month A symposium on race, racism, excellence and America. Bari Weiss

https://bariweiss.substack.com/p/condoleezza-rice-coleman-hughes-and?token=

Why does Condoleezza Rice celebrate Black History Month? Because, as the former Secretary of State told me last week during a wide-ranging interview: “When I was a little kid growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, in fourth grade, we had a book called ‘Know Alabama.’ And you would never have known that there were any black people as part of that history. So I think it’s important to call out.”

What is the meaning and purpose of Black History Month?

Does it risk emphasizing the false idea that black history is separate from American history? Or is it an acknowledgement of the essential black contribution toward creating a more perfect union? Does it allow us to step back and see, as Coleman Hughes writes below, not just what the country has done to black people but what black people have done for the country? Or does its existence reify the idea of race—and, in so doing, perpetuate the myth that we are somehow not all equally American?

In honor of Black History Month, we reached out not only to Coleman, but also to Daryl Davis, Eli Steele, Ronald Sullivan, Sheena Mason, Noah Harris and Brittany Talissa King.

Read their thoughtful contributions below. And you can listen to my whole conversation with Secretary Rice here:

Transcending Victimhood and Fostering Black Excellence

By Coleman Hughes

To be black in America is to be seen, above all, as a victim. Regardless of the unique mix of privileges and disadvantages that have characterized your life, “anti-racism” will label you a victim of oppression. We live in the age of the 1619 Project, an age that tries to convince us of myths large and small: that the American revolution was fought to preserve slavery, for instance. Or that Excel spreadsheets are part of the legacy of white supremacy.

Against this trend stands Black History Month, the only history-related, race-conscious tradition in America that focuses not on what the country has done to black people, but on what black people have done for the country. Its focus on achievement rather than victimhood was an intentional choice by Carter G. Woodson, the black historian who founded Negro History Week in the 1920s, which later became Black History Month.

Woodson cited the trajectory of Native Americans—a group who “left no continuous record” and whose prosperity as a group was hampered as a result—as a cautionary tale. On the other side, he cited the Jews—who have a long and continuous written record of their history—as an example of a group that “in spite of worldwide persecution” became “a great factor in our civilization.”

The original point, in other words, was to foster black excellence through a kind of benign race-conscious education: one focused more on our achievements than on our suffering. As a result of its focus on achievement, a certain contingent of people have always viewed Black History Month as too sanguine. It should focus more on slavery and Jim Crow and less on inventors and poets, they argue. I would argue back: the image of the black American as a victim was always intended to be a short-term strategy to secure our rights. It was never meant to become a permanent identity. There is no dignity in being America’s eternal guilt mascot. There is dignity, however, in achievement and success—in becoming, as Woodson put it, a great factor in civilization. To that end, I submit that we should keep Black History Month the way it is.

Coleman Hughes is the host of Conversations with Coleman.

Upsetting the Oppressor’s Agenda

By Eli Steele

Carter G. Woodson, the father of Negro History Week, wrote: “If you make a man feel that he is inferior, you do not have to compel him to accept an inferior status, for he will seek it himself.”

The same man also wrote: “If you teach the Negro that he has accomplished as much good as any other race he will aspire to equality and justice without regard to race. Such an effort would upset the program of the oppressor in Africa and America.”

The America in which Woodson wrote those words was a harshly segregated one where folks like my own grandfather, born to ex-slaves, could only rise to the level of a truck driver despite possessing the brilliance of an Ivy League professor. While my grandfather never allowed himself to be stigmatized as racially inferior, there were many blacks who did, and Woodson sought to liberate them with examples of black achievement.

Never would he have imagined that his Negro History Week would morph into a corporatized Black History Month, corrupted by noblesse oblige from privileged whites and blacks invested in upholding the white-oppressor and black-victim dichotomy.

Every February, we partake in the empty ritual of opening Black History Month emails from corporations advertising social justice messages that can be summed up as: “There is more work to be done.” The lie here is that this “work” does not lead to freedom or a better society. The “work” here means labeling “equality and justice”—the very values that Woodson saw as the key to freedom for all—as vestiges of white supremacy that must be dismantled along with other American principles.

The tragedy of today’s America, Black History Month being only one symptom, is that so many of us have fallen into the trap of seeking our own inferiority. For those of us who refuse this path, Black History Month has no meaning because we have “upset the program of the oppressor” by seeking to become fully realized Americans.

Eli Steele is a documentary filmmaker. His latest film is “What Killed Michael Brown?”

Do Away With It: Black History Is American History

By Daryl Davis

There was a time when Black History was not taught at all. What was taught was American history. But it may as well have been called white history, because white people were being given credit for things they did not invent and did not discover.

We had to fight hard and long to get some of our history taught. We finally got one week. It was established in 1926. Then, in 1976, Negro History Week became Black History Month. It’s no coincidence that it was also the shortest month of the year.

This started as a positive influence. But it has become detrimental and is subliminally producing the wrong results with whites and blacks, kids and adults alike.

Here’s the problem: Every February, school-age children learn about half a dozen black people, such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Charles Drew, and perhaps one or two more. By the time the teachers have gotten through this list, the month is over, and it becomes, “Okay, we did our black thing. Now let’s move on.” Those half-dozen black people are never revisited during the rest of the school year.

The reinforcement of Black History Month only comes each subsequent February, when the kids only learn about the same handful of black people. What about the many others who are never mentioned? We’re told, “We ran out of time.” Both white and black kids are essentially being brainwashed into believing these particular half-dozen black people were the only ones in this country who did anything significant.

I say we take the information from Black History Month and place it where it belongs, under the umbrella of American history, so it can be taught all year long like everything else.

Daryl Davis is an R&B musician who has performed with Chuck Berry and B.B. King. He is the subject of the 2016 documentary “Accidental Courtesy: Daryl Davis, Race & America.”

To Transcend Racism We Have to Transcend the Idea of Race Itself

By Sheena Mason

Black History Month is a result of the Law of Racialization: To every racist action, there is an equal and opposite counter-racist reaction.

We should not be fooled into thinking Black History Month signifies our liberation from the racist past. Rather it is evidence of it: Racist ideas about people who had been deemed “black” prompted a celebration by those same people.

This is an entirely understandable way of responding. And it ultimately reifies the myth of race. And we cannot transcend racism unless we transcend our belief in race itself.

There is a tendency to think that unraveling race—becoming raceless—is somehow “white.” Nonsense. Racelessness is not whiteness or ordinariness. It does not signal a lack of heritage or history or culinary or spiritual richness. Instead, racelessness signifies our transcendence of racism and the ushering in of our healing and unification.

A post-racist world should be embraced by anyone who wants to liberate themselves from the nefariousness of our belief in “race.” If we fail to do this—if we continue to conflate ethnicity, culture, and history with “race”—we will simply perpetuate the same thing many of us claim we want to end: racism.

There may be some fear that in undoing our belief in race we will lose something. It’s true that in such a post-racist world, Black History Month would be seen as a relic of the past. Yet, that would signal our liberation from racism, a celebratory occasion. Who we are cannot be taken from us. To undo our belief in “race” the only thing we lose is the false realities racism causes for all of us.

Sheena Mason is an assistant professor in English at SUNY Oneonta and the president and co-founder of Theory of Racelessness.

My Ancestors Picked Cotton. I Am the First Student-Body President of Harvard.

By Noah Harris

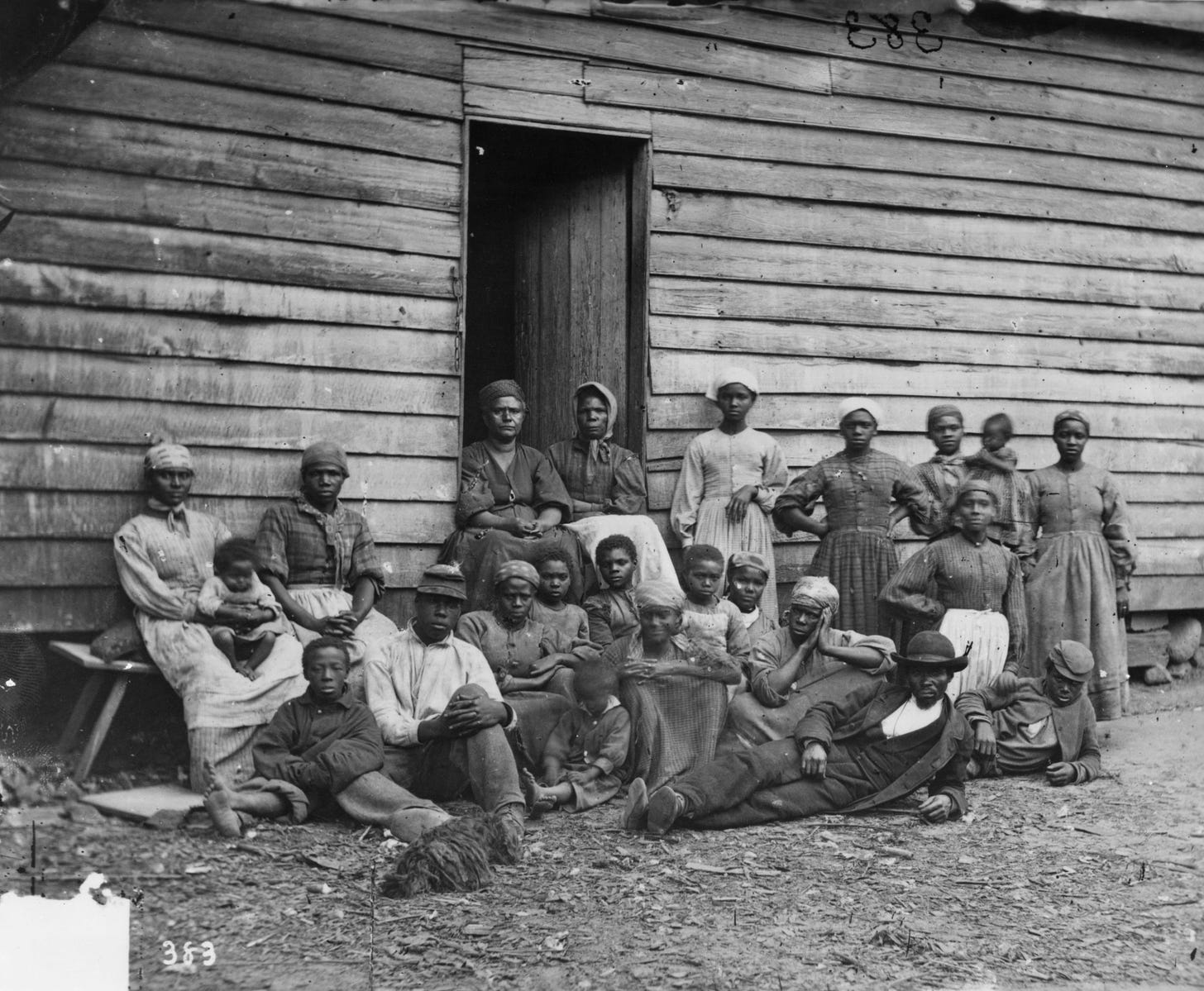

My ancestors picked cotton in Mississippi. I am the first Black man elected student body president in Harvard’s 386-year history. The journey of my family—and that of so many others—represents a people who fought relentlessly for generations so their children could have a better life than they did.

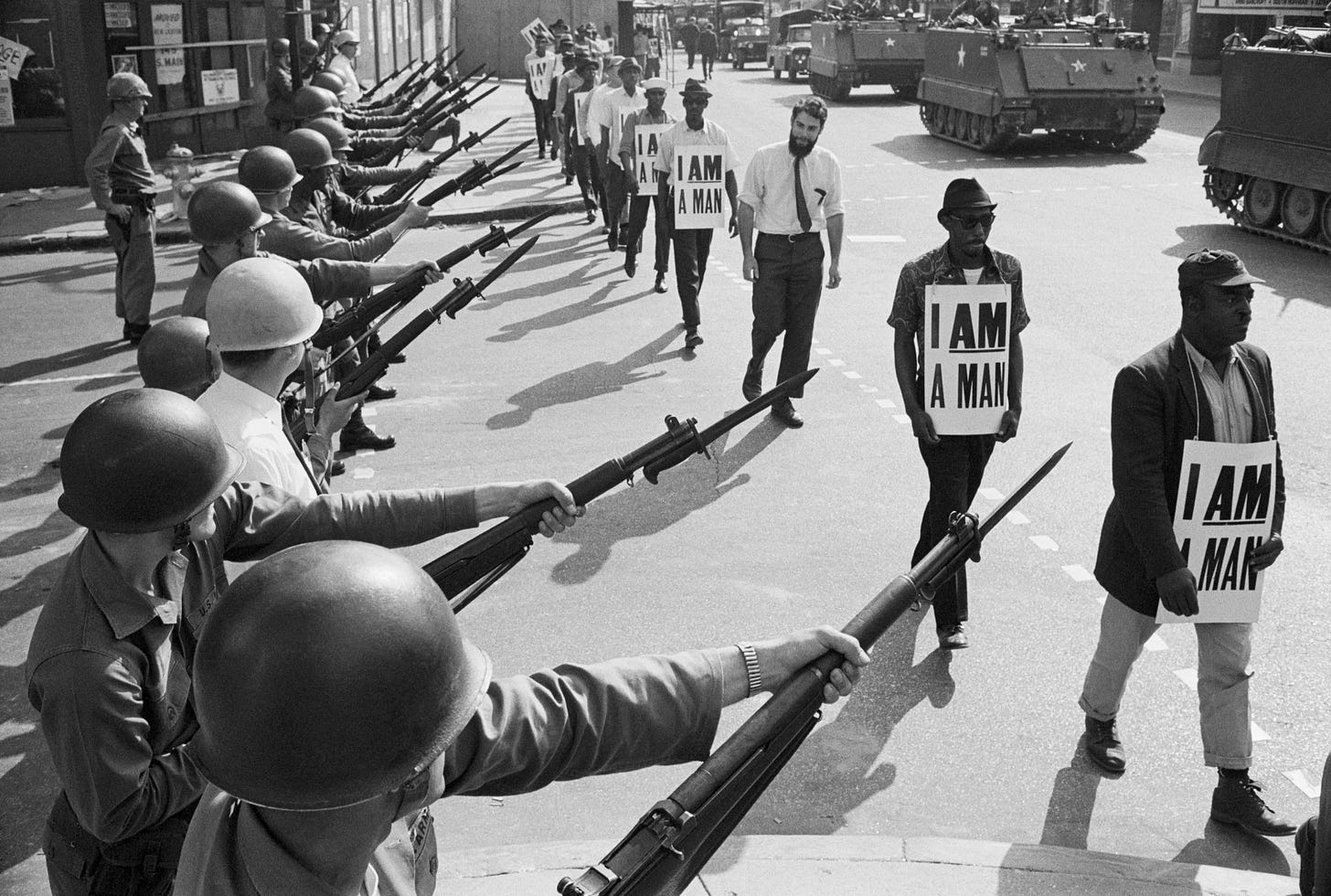

That lineage of black excellence traces back to my great great great great grandfather, a sharecropper in the late 1800s who became the first black constable in Washington County, which is on the Arkansas border. Four generations later, in the 1960s, my grandparents on both sides of my family marched for equal rights. My grandmother was even arrested and sent to the ruthless Parchman Prison. Because of the rights they fought for, my parents became the first in my family to go to college, and they created the opportunity for me to reach unimaginable heights.

Black History Month is about drawing on all the striving and achievements of the past four centuries and looking to the future. That’s a reason for hope, but, for young people especially, it can be painful because we learn and talk about and celebrate the dream—the dream of a fully realized equality—and we wonder how long it will be until that is fulfilled. My generation hopes to live in an America where the racial wealth gap will no longer exist, voting rights are second-nature, and the criminal justice system works for everyone. We want to feel like we belong in the most prestigious offices—especially the ones that we have never seen ourselves in before. We hope for a time when the color of our skin is merely what makes us special, not a blemish that negatively affects how America treats us. Black History Month gives America the space to continue striving to be the best version of itself, and it reminds us that, after all the wandering through the desert, we are not in the Promised Land yet.

Noah Harris is a senior at Harvard.

Be Proud of Your Heritage

By Brittany Talissa King

The question, “Why Should We Celebrate Black History Month?” seems less and less rhetorical as our cultural conversations become more divided. Is this holiday celebratory? Or is it segregationist? How you answer those questions depends on how you understand the term “black.”

Let’s go back to 1967, to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Georgia, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made an enthusiastic address to Black Americans.

Martin explained: “If the [Black American] is to be free, [you] must move down into the inner resources of [your] own soul and sign with a pen and ink,” expounding that “no document can do this for us.” Here, King illustrates personal freedom from racial identity. The talk went on and he concluded this way: “Be proud of our heritage,” he said. “I’m Black, and I’m proud of it. I’m Black and beautiful!”

King didn’t double-speak here. Lay down your racial identity, he insisted. But elevate—celebrate—your ethnicity.

There’s a critical difference between these categories. As someone can be “white” and “Scottish” or “white” and “Swedish,” or “black” and “Nigerian” the same goes for “black” and “Black American.” Our race is what marked us without our consent. After African people were stolen from their original homes and enslaved as property for America. They were not a homologous group. They were manufactured together with no legal identity and orphaned from their ethnicities.

And despite the nation’s original plans for us, we became a new people and cultivated a new heritage.

From property to citizens. A story of triumph.

Black History Month doesn’t memorialize race. It honors the impossible that transpired despite it. Who wouldn’t want to celebrate that?

Brittany Talissa King is a freelance writer and journalist.

How We Made the Impossible Possible

By Ronald Sullivan

America should understand Black History Month as both descriptive and prescriptive. Black History Month describes an ugly history, fueled by white supremacy and justified by notions of black inferiority as biological, heritable, and pre-ordained. Black History Month rebuts these ideas. It provides a different narrative—one that properly situates black contributions to America and the world. It supplants one description with a better, historically accurate one by showcasing black brilliance and beauty, and reminds America of blacks’ unique contributions to the idea of America, as well as its culture. So long as white supremacy operates in the hearts and minds of the citizenry, Black History Month is a needed antidote.

Black History Month is also prescriptive. The history of black folk in America shows a remarkable resilience, and provides a roadmap for the future. As James Baldwin eloquently puts it, black history, like America’s history, is the history of making the impossible possible. Blacks were brought to American shores as chattel. They were given no formal education, received woefully inadequate medical care, and were considered less than human. It is nothing short of remarkable that in relatively few generations blacks compete at the highest levels on every intellectual, artistic, and athletic register in our country. Children can view this upward

trajectory as a source of inspiration and strength, knowing that blacks have not only survived this blip in world history, but have thrived. Black History Month, at once, reminds blacks of their past and points to their potential.

Ronald Sullivan is a professor at Harvard Law School.

Comments are closed.