Yes, Critical Race Theory Is Being Taught in Schools A new survey of young Americans vindicates the fears of CRT’s critics. Zach Goldberg Eric Kaufmann

https://www.city-journal.org/yes-critical-race-theory-is-being-taught-in-schools

To what extent, if at all, are critical race theory (CRT) and gender ideology being taught or promoted in America’s schools? With little data available, and no agreement about what constitutes the teaching of critical social justice (CSJ) ideas, the answer up to now has remained open to political interpretation.

Motivated by the work of Manhattan Institute senior fellow and City Journal contributing editor Christopher F. Rufo, many on the right allege that CRT-related concepts—such as systemic racism and white privilege—are infiltrating the curricula of public schools around the country. Educators following these curricula are said to be teaching students that racial disparities in socioeconomic outcomes are fundamentally the result of racism, and that white people are the privileged beneficiaries of a social system that oppresses blacks and other “people of color.” On gender, they are being taught that gender identity is a choice, regardless of biological sex. But are the cases Rufo and others point to representative of American public schools at large—or are they merely outliers amplified by right-wing media?

The response to these charges from many on the left has been to deny or downplay them. CRT, they contend, is a legal theory taught only in university law programs. Therefore, what conservatives are up in arms about is not the teaching of CRT, but the teaching of America’s uncomfortable racial history.

But strong connections exist between the cultural radicalism of CRT and the one-sided, decontextualized portrayal of American history and society that Democratic activists endorse. And these ideas have also influenced many Democratic voters. Indeed, according to a 2021 YouGov survey, large majorities of Democratic respondents support public schools’ teaching many of the morally and empirically contentious ideas to which opponents of CRT object. These include the notions that racism is systemic in America (85 percent support), that all disparities between blacks and whites are caused by discrimination (72 percent), that white people enjoy certain privileges based on their race (85 percent), and that they have a responsibility to address racial inequality (87 percent).

Whatever one thinks of these ideas, they are hardly “settled facts” on the same epistemic plane as heliocentrism, natural selection, or even climate change. To the contrary, they are a moral-ideological just-so theory of group differences, an all-encompassing worldview akin to a secular religion, whose claims can’t be measured, tested, or falsified. They treat an observed phenomenon (disparate group outcomes) as evidence of its cause (racism), while specifying causal mechanisms that are nebulous, if not magical. Their advocates have not refuted counterarguments; they’ve merely asserted empirically unverified statements about the nature of group differences.

Publicly funded schools that teach and pass off left-wing racial-ideological theories and concepts as if they are undisputed factual knowledge—or that impart tendentiously curated readings of history—are therefore engaging in indoctrination, not education. The question before us, then, is not whether or to what extent public schools are assigning the works of Richard Delgado, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and other critical race theorists. It is whether schools are uncritically promoting a left-wing racial ideology.

To answer this and other related questions, we commissioned a study on a nationally representative sample of 1,505 18- to 20-year-old Americans—a demographic that has yet to graduate from, or only recently graduated from, high school. A complete Manhattan Institute report of all the findings from this study will be published in the coming months; what follows is a preview of some of them. Our analysis here focuses mainly on the results for the sample overall rather than for various subgroups.

We began by asking our 18- to 20-year-old respondents (82.4 percent of whom reported attending public schools) whether they had ever been taught in class or heard about from an adult at school each of six concepts—four of which are central to critical race theory. The chart below, which displays the distribution of responses for each concept, shows that “been taught” is the modal response for all but one of the six concepts. For the CRT-related concepts, 62 percent reported either being taught in class or hearing from an adult in school that “America is a systemically racist country,” 69 percent reported being taught or hearing that “white people have white privilege,” 57 percent reported being taught or hearing that “white people have unconscious biases that negatively affect non-white people,” and 67 percent reported being taught or hearing that “America is built on stolen land.” The shares giving either response with respect to gender-related concepts are slightly lower, but still a majority. Fifty-three percent report they were either taught in class or heard from an adult at school that “America is a patriarchal society,” and 51 percent report being taught or hearing that “gender is an identity choice” regardless of biological sex.

We also wanted to assess whether certain concepts were more likely to be taught in some educational contexts than in others. To this end, we separately asked respondents whether, “in high school, college, or other educational settings,” they were ever taught that “discrimination is the main reason for differences in wealth or other outcomes between races or genders” or that “there are many genders, not just male and female.” Overall, excluding those who didn’t know, 62 percent were taught that discrimination is the main reason for outcome gaps and a third were taught that there are many genders. As shown in the chart below (which includes “don’t know” answers), statistically significant (if only modest) differences emerged between respondents with no versus at least some prior college instruction: 58 percent and 26 percent of those in the latter group, respectively, report having been taught these two concepts, compared with 50 percent and 25 percent of those in the former. Far from being the preserve of academic curricula, then, CSJ ideas central to contemporary left-wing racial and gender ideology are being taught to students before they arrive at college.

The summary chart below underscores the pervasiveness of at least some form of exposure to these concepts. For instance, 93 percent of respondents reported either being taught (85 percent) or hearing from an adult at school about at least one of the eight listed concepts, with an average of 4.3 concepts; 90 percent reported either being taught (80 percent) or hearing about at least one of the five CRT-related concepts, with an average of 3.0 concepts; and 74 percent reported either being taught (54 percent) or hearing about at least one of the three gender-related concepts, with an average of 1.3 concepts. While these figures are for the sample overall, they do not meaningfully differ by school type. Levels of exposure were similar regardless of whether respondents reported attending public or private high schools.

Perhaps it’s wrong to assume that the teaching of these CSJ concepts necessarily amounts to ideological indoctrination. After all, such concepts are salient on social and other media, and have also been uttered or invoked by prominent politicians. Perhaps, then, most teachers are merely using them as fodder for healthy classroom debate or presenting them as perspectives among other competing ideas.

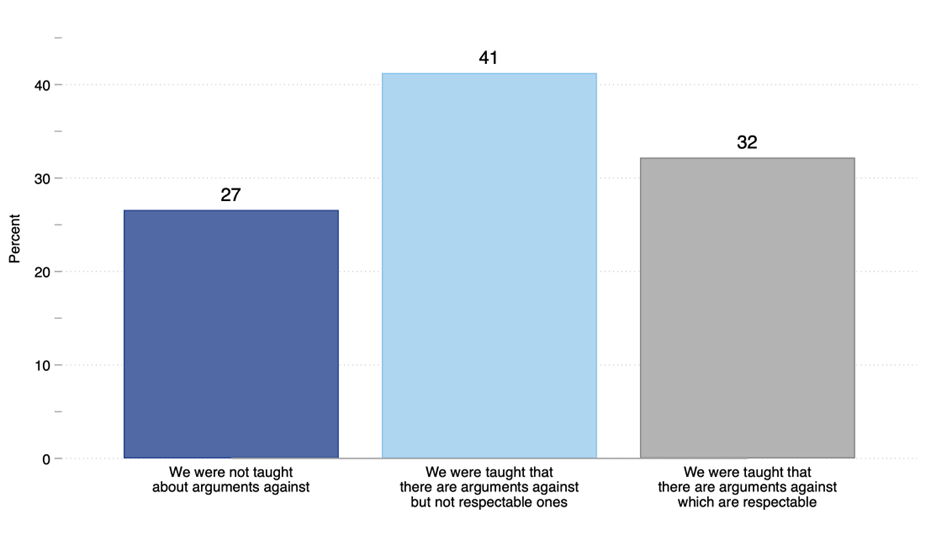

Yet our data suggest that this is hardly the majority experience. Specifically, we asked those who reported being taught at least one of the listed concepts in a high school class what, if anything, they were taught about arguments opposing them. As shown in the chart below, 68 percent responded that they either were not taught about opposing arguments or were taught that there are no “respectable” opposing arguments. Importantly, this rate does not meaningfully vary by race, political orientation, or high school type. Whites (30 percent) and nonwhites (34 percent), Democrats (29 percent) and Republicans (31 percent), liberals (29 percent) and conservatives (31 percent), and public (32 percent) and private or parochial (28 percent) schoolers were equally likely to report being told about respectable counterarguments. No evidence, then, suggests that this response reflects respondents’ political biases. Instead, the data suggest that large majorities in all groups have been given the impression that the concepts they were taught are beyond reproach. And these data hardly tell the full story: in our forthcoming report, we additionally show that the number of concepts respondents report being taught is positively related to the probability of being told there that opposing arguments are not “respectable.”

If this isn’t indoctrination—unwitting or otherwise—then what is?

The prevalence of students’ classroom exposure to left-wing ideological concepts raises the question of its attitudinal effect. Are students who report receiving such instruction more “woke” than those who do not? Given the many other sources of attitudinal influence with which any effect of exposure must compete, there is ample reason for skepticism. At the same time, our respondents are in a phase of life in which, by some accounts, social and political attitudes are malleable.

The potential for exposure to shape related attitudes is plausible. In fact, in a dissertation chapter, one of us found that having white respondents read a short “racially woke” op-ed article led to eight- to 12-point increases (mostly via increases in collective shame and guilt) in support for race-based affirmative action, government assistance, and reparations to African-Americans. If attitudinal shifts of this magnitude can be produced over a span of just minutes, what might be the effects of more protracted exposure?

It’s also fair to say that many educators incorporating such concepts into their instruction expect, or at least hope, that doing so makes a difference in the minds of students. Indeed, the notion that concepts like “white privilege” and “systemic racism” are solely taught for knowledge’s sake strains credulity, especially when such instruction usually entails the omission or delegitimization of competing arguments. The hope instead seems to be that students will come to see white people as ultimately responsible for the creation and persistence of racial inequality; and that this realization will inspire support for race-conscious, “equity”-oriented policies.

Perhaps this hope is ill-founded, but our data indicate otherwise. As an initial test, we examined whether those who report being taught a given concept are more likely to endorse it. For instance, the chart below shows that, relative to those who reported they were not taught the related concept, those who indicated they were taught it were 14 points more likely to agree that the black-white pay gap is mainly due to discrimination, 15 points more likely to agree that “being white is one of the most important sources of privilege in America,” 23 points more likely to agree that “white people have unconscious biases that negatively affect non-white people,” and 29 points more likely to agree that “America is built on stolen land.” These differences, all statistically significant at the 99.9 percent level, persist after adjustments for a host of theoretically plausible alternative explanations, including race, political orientation, county rurality, county partisanship, county racial liberalism, and county school segregation.

If the effects of CSJ-related instruction were entirely limited to the above, its proponents would likely be disappointed. For what good is increasing agreement with CSJ-related concepts if that agreement doesn’t translate to increased support for “anti-racist” policies? However, because such policies discriminate on the basis of race and can thus be regarded as unfair, increasing support for them—particularly among whites—may not be so easy. To this end, it’s important that instruction increases the justifying belief that white people are to blame for (and thus are responsible for rectifying) black disadvantage.

Our next analysis thus examines whether the volume of CRT-related classroom exposure—which we define as the total number of CRT-related concepts respondents reported being taught in school (from zero to five) affects attitudes toward white Americans and pro-black policies like affirmative action and race-based government assistance.

First, we consider whether exposure to a larger share of the five concepts increases agreement with the view that white Americans “are ultimately responsible for the inferior social position of black people.” Referring to the dark blue bars in the chart below, this indeed appears to be the case. Support is lowest (32 percent) among those who didn’t recall being taught any of the five CRT-related concepts (the “no exposure” group), and agreement rises—albeit non-linearly—to a high of 75 percent among those who report being taught all five concepts. Adjusting for alternative explanations has a minimal effect on this 43-point difference in attitudes between those taught no CRT concepts and those taught all five, which remains statistically significant.

We next consider whether exposure increases agreement with the broad-brush generalization that white Americans are “racist and mean”—an item one of us has previously tested and used as an indicator of collective moral shame among whites. As denoted by the light blue bars, agreement with this statement begins at a low of 40 percent among those in the “no exposure” group and increases (again non-linearly) to a high of 72 percent for those who report being taught all five concepts. This difference remains significant when controlling for alternative explanatory variables.

If greater CRT-related classroom exposure increases the endorsement of negative moral appraisals of white Americans, we’d also expect it to boost support for group-based policies that afford preferential treatment to African Americans—even when descriptions of such policies explicitly speak to the risk of discrimination against whites (as our measure of support for affirmative action, adopted from the General Social Survey, does). Consistent with this prediction, our data show that support for the preferential hiring and promotion of black people falls to a low of 17 percent among those who reported hearing no CRT, while reaching a high of 44 percent among those who reported being taught all five CRT-related concepts. Similarly, the belief that the government should help black people (versus “our government should not be giving special treatment to black people”) is endorsed by 35 percent of those in the “no exposure” group, compared with 43 percent of those who reported being taught one concept, 51 percent to 54 percent of those who reported being taught two to four concepts, and 72 percent of those who reported being taught all five concepts. Again, a 30- to 40-point difference emerges between those who were not taught CRT material and those who received the maximum dose of it.

Here we should note that the above results are similar for white and non-white respondents alike—even if not always to the same degree. One relationship that is necessarily exclusive to whites, though, is that between exposure and white guilt, which is shown in the chart below. Whereas 39 percent of whites who did not report any CRT-related classroom exposure indicated feeling “guilty about the social inequalities between white and black Americans,” this share rises to about 45 percent among whites who reported being taught one or two CRT-related concepts, and to between 54 percent and 58 percent among whites who reported being taught three or more concepts.

These findings indicate that those reporting being taught more CRT-related concepts are more likely to endorse negative moral appraisals of and to view white Americans as responsible for black disadvantage. Among whites, greater CRT exposure is also linked to higher levels of guilt over racial inequality. Finally, and perhaps consequently, greater CRT exposure predicts a higher likelihood of both white and minority young people supporting race-conscious policies that afford preferential treatment to African-Americans. The same is true for gender. Among those that were taught that gender is a choice, 53 percent say “the gender we identify with is more socially given than determined by our biology” compared with 40 percent of those who were not taught this, a significant difference. Those taught about gender as an identity are more likely to view it as detached from biological sex.

While we can’t be certain that exposure causes attitude change—those with progressive attitudes could have had parents more likely to select into schools where CRT is taught (or to recall being exposed to it)—we used data from a person’s zip code and county (rurality, diversity, education, voting patterns) that make such competing explanations unlikely. We can also rule out the possibility that these relationships are the product of alternative explanatory factors in our dataset.

While only scratching the surface of what will feature in the full report, our findings have several important takeaways.

First, the claim that CRT and gender ideology are not being taught or promoted in America’s pre-college public schools is grossly misleading. More than nine in ten of our respondents reported some form of school exposure to at least some CRT-related and critical gender concepts, with the average respondent reporting being taught in class or hearing about from an adult at school more than half of the eight concepts we measured. Eight in ten reported being taught in class at least one concept central to CRT and contemporary left-wing racial ideology, with the average respondent reporting being taught two of the five we listed. A majority were taught radical gender ideas. Given the sheer size of these numbers, the promotion and teaching of “white privilege” and “systemic racism” in America’s public schools can hardly be regarded as a rare or isolated phenomenon. It is the experience of a sizeable share of pre-college students.

Second, educators are presenting CSJ ideas to students uncritically. If such concepts were presented only as perspectives—and in conjunction with competing others—then their introduction into the classroom could very well be defensible. But our data suggest that this is not the case. Instead, most are receiving them as undisputed “facts”—or at least facts only disputed by bigots and ignoramuses. This is indoctrination, and governments should act swiftly to put a stop to it. More-detailed policy recommendations must await the full report. But schools and teachers that wish to teach about these concepts should be given the option of either teaching the diversity of thought surrounding them or being barred from teaching them altogether.

Third, such biased instruction is effective. Our data show that those who report being taught CRT-related concepts are not only more likely to endorse them but are also more likely to blame white people for racial inequality, to essentialize white people as “racist,” and to support “equity-oriented” race-based policies. Among whites, we also observe higher levels of white guilt among those exposed to more CRT-related concepts.

Overall, then, our data would appear to confirm many of the fears of anti-CRT activists about such instruction. Anecdotes are borne out by our representative large-scale data.

Critical race and gender theory is endemic in American schools. The vast majority of children are being taught radical CSJ concepts that affect their view of white people, their country, the relationship between gender and sex, and public policy. For those inclined toward a colorblind and reality-based ideal, these findings should serve as a wakeup call. Unless voters, parents, and governments act, these illiberal and unscientific ideas will spread more widely, and will replace traditional American liberal nationalism with an identity-based cultural socialism.

Photo: breath10/iStock

Comments are closed.