Charles Fain Lehman The Paradox of Jewish Liberalism What use is a Jewishness that blinds you to hatred of Jews?

https://www.city-journal.org/article/the-paradox-of-jewish-liberalism

After the October 7 terrorist attack, many American Jews have stomached two shocks: the shock of Hamas’s brutality, and the shock of their putative political allies’ support for the brutes. Liberal Jews are not only horrified by campus chants of “there is only one solution: Intifada, revolution.” They are also surprised.

Less surprised are those of us among the one in six American Jews who are conservatives. The anti-Semitic elements of the American Left, from funders to campus activists, have been obvious for years, even decades. It is at turns refreshing and off-putting, therefore, to see other Jews wake up to what we already knew.

At this moment, Jewish conservatives should resist any compulsion to tell their liberal brethren “I told you so.” This is an opportunity, rather, for making hard truths plain. Many American Jews are liberals out of a profound, identity-level connection between their Judaism and their liberalism—a connection that developed alongside Jewish-American identity. It is this association that consistently blinds them to the anti-Semitism of others on the left; only by unearthing this tension can they overcome it.

American Jews, it should be emphasized, are remarkably liberal. In Pew’s 2020 survey of Jews, 71 percent identified as Democrats, versus 26 percent as Republicans. Half of Jews describe themselves as “liberal” compared with 16 percent “conservative” and the remainder “moderate.” By these proportions, Jews are more Democratic than Hispanics, Asians, and Muslims; they are more liberal than blacks. Jews are also more Democratic than those who earn as much as the average Jewish household does. As Milton Himmelfarb, the longtime research director of the American Jewish Committee, famously put it, “Jews earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans.”

Most Jews, in fact, express their Jewish identity through liberal values. Asked by Pew which aspects of Judaism were “essential” to what it means to be Jewish, Orthodox Jews said leading an ethical and moral life, observing Jewish law, and continuing family traditions—all of which are, if not the same, then highly related for observant Jews. For the non-Orthodox, though, the top slots went to remembering the Holocaust, leading an ethical and moral life, working for justice and equality, and being intellectually curious. These last two, especially, identify Judaism with liberal values of intellectual independence and commitment to social justice.

This association between Judaism and liberalism is not new. Since Jews first immigrated to the United States, they have articulated their identity in the language of liberalism. Indeed, Jewish ethnogenesis—the process by which Jews became Jewish-Americans—has often entailed making Judaism synonymous with progressivism.

That was true among the first major wave of Jewish immigrants, who arrived from Germany in the mid-nineteenth century. These new Americans brought with them the roots of modern reform Judaism, which emerged out of and was inspired by a move toward Enlightenment rationalism within German Jewry. American Jewish leaders of this era strove to make Judaism liturgically similar to Protestant Christianity, sometimes forgoing the rules of kashrut and in some cases even observing the Sabbath on Sundays. In their efforts to assimilate to the culture of the Progressive era, Jews also founded secular moral uplift organizations like the Young Men’s Hebrew Association and the Ethical Culture movement. In this, too, Jews were seeking to assimilate to the norms of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant society. Because that society was—in a nineteenth-century way—progressive, so too was Jewish assimilation.

The German Jews were soon to be dramatically outnumbered by Eastern European Jews, nearly 3 million of whom arrived as part of the great wave of migration between 1880 and 1920. Many of the Eastern Europeans brought along a devout commitment to socialism. During the 1920s, Jews accounted for 10 percent of the American Communist Party. New York City’s Jews sent two of the first socialists to the U.S. House of Representatives: Meyer London of the American Socialist Party and Vito Marcantonio of the American Labor Party (Marcantonio was supported by Italians, Jews, and Puerto Ricans). The intensity of these Jews’ commitment to socialism eventually faded, as distance from the old country and the horrors of Stalinism made them an integral part of the New Deal coalition. But they retained a basic commitment to universalistic social justice as a secular expression of Jewish values.

Compounding these ideological roots is the way that Jews have benefited from liberalism. This is true insofar as liberal tolerance has made America the safest country on earth for Jews, ever since George Washington’s letter to the Jews of Newport. But it is also true insofar as the story of Jewish advancement in the twentieth century is a canonically liberal one. Jews have long had what Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan referred to as “the passion for education”; in 1955, 62 percent of Jews of college age were in school, compared with 26 percent of the general population. For many years, Jews were barred from the nation’s best schools by secret admissions policies; when they were finally admitted, the schools were quickly filled with Jewish students. In other words, Jews rose to so many positions of prominence in the postwar order through individual academic merit and the overcoming of prejudice—the liberal ideal of social mobility.

Liberalism, in other words, has given a great deal to the Jews. And Jews, in return, have given a great deal to liberalism—as leaders, but also on the level of collective values. To reap the rewards America offered, many Jews rearticulated their values in universalistic terms; so that they might no longer dwell apart, American Jews made liberalism the universalizing substitute for particular, tribal identity.

This profound connection to liberalism is, among other things, almost certainly why Jews are convinced that it is the Right that has an anti-Semitism problem. In Pew’s survey, 52 percent of respondents said that they believe the Democratic Party is friendly toward Jews, while just 10 percent thought it was unfriendly. The equivalent figures for the Republicans are 29 and 26 percent. (The remainder is neutral.) Jews are overwhelmingly convinced that Democrats like them, but they are far less certain about the GOP.

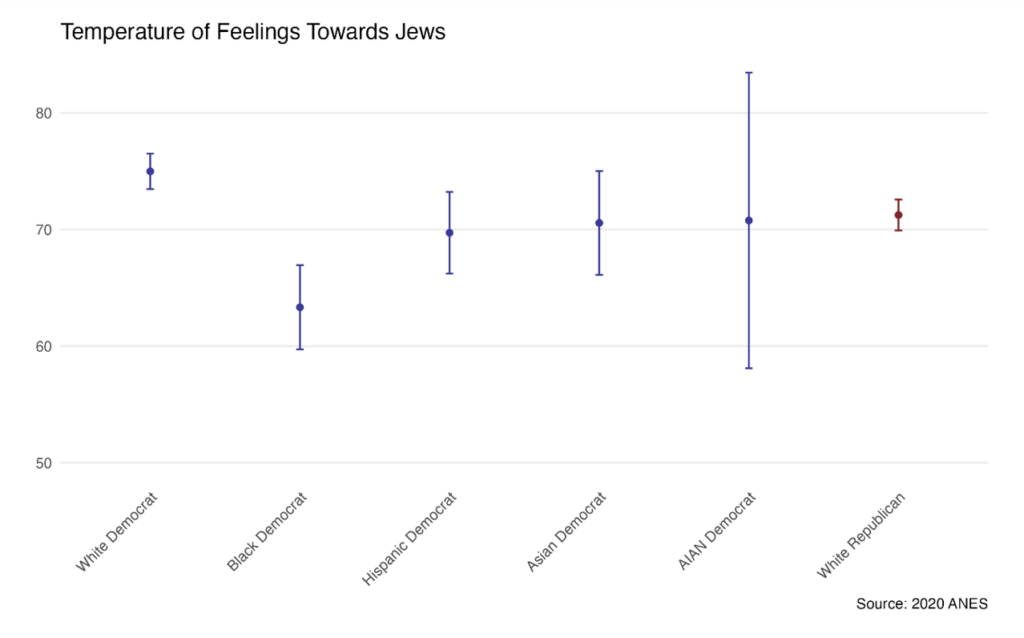

This is remarkable because, on balance, the two parties’ bases are quite similar in their views of the Jews. In the 2020 American National Election Study (ANES), respondents were asked how warmly they felt toward Jews (among other groups) on a scale of 0 to 100. Democrats (including leaners) gave Jews a 73 on average, Republicans just two points less. And the two groups were equally unlikely to give Jews less than a 50, equivalent to feeling “cool” toward them.

This similarity is in part a function of composition. Democrats are younger than Republicans, and young people are—in the ANES data—cooler on Jews than older people. More importantly, the Democratic coalition contains more nonwhite people. As the figure above shows, white Republicans are significantly cooler toward Jews than are white Democrats. But Hispanic and Asian Democrats feel about the same as, or a little cooler than, white Republicans. Black Democrats are substantially colder—almost 12 points more than white Democrats.

Put age and race together, and left-wing anti-Semitism becomes a real problem. For a 2022 paper, political scientists Eitan Hersh and Laura Royden surveyed 3,500 people, including 2,500 18- to 30-year-olds, about their agreement with statements meant to measure anti-Semitism. They found that older black and Hispanic respondents were only a bit more likely to agree with statements like “Jews are more loyal to Israel than to America” and “Jews in the United States have too much power.” But blacks and Hispanics 30-and-under were 16 points more likely to agree compared with whites from the same age cohort. In fact, the young black and Hispanic respondents in their answers most closely resembled white respondents who identified with the alt-right.

To be sure, only minorities of nonwhite Democrats are anti-Semitic. But the same is true of Republicans, white or otherwise, and it seems like the difference comes out in the statistical wash. A rational Jewish voter would attend to the threat of anti-Semitism in both parties equally, at least on grounds of self-interest. Instead, liberal Jews ignore left-wing anti-Semitism over and over again—then act surprised when it becomes too big to ignore.

This is the paradox at the heart of American Jewish identity. To be Jewish in America is, for many Jews, to be a liberal, an identification with deep roots in American Jewish history. But inhabiting that identity requires disregarding the anti-Semitic rot that has infested mainstream liberal institutions, and that threatens from both sides of the political spectrum.

This paradox is itself reflective of an absence—that of ethnic self-preservation as an instinct prior to liberal values. Indeed, it is this self-preservation drive that liberalism is in tension with. As Irving Kristol once put it, “Whereas once upon a time it was not unreasonable to ask whether a given turn of events or policy was ‘good for the Jews,’ to ask that question in the United States today in Jewish circles is to invite a mixture of ridicule and indignation: Ridicule at the retrograde parochialism of such an attitude; indignation at the suggestion that there is such a thing as a Jewish interest distinct from the interests of mankind as a whole.”

If this Jewish universalism was ever a viable model, its time has passed. Rising apathy toward Jews, and especially toward Israel, among younger generations, suggests that in the near future American Jews will no longer be able to rely on general philo-Semitism. Rather, they will need to carefully pick and choose their political allies.

This does not always mean aligning with the political Right, which, on its fringes, has its share of Jew haters. But it does mean not spurning would-be allies on silly pretexts. American evangelicals, for example, love Jews, while Jews dislike them, often on the bizarre grounds that they like Jews “too much.” Anyone with a passing familiarity with the history of anti-Semitism cannot take seriously the idea that liking Jews too much is a real problem. More generally, Jews cannot continue to give away their ideological allegiance for free. Tikkun Olam is no longer an adequate reason to vote for the Democrats. Jews should stake their votes, if not on group interest, then at least on group preservation.

Conservatives, meanwhile, should recognize the political opportunity to incorporate Jews, like other high-achieving ethnic minorities, into their coalition. They can do this not by frontloading high-minded values but by emphasizing their commitment to combatting anti-Semitism in all its virulent forms. The rise of left-wing anti-Semitism in other Anglosphere countries has, in fact, pushed their Jewish populations toward right-wing parties. Such a realignment is possible here, but only if Jewish voters and the American Right will it to be so.

Comments are closed.