The Prophets: D.A. Henderson Years before Covid, the scientist credited with eradicating smallpox warned against shutting down the world to combat an epidemic. Joe Nocera

Welcome back to The Prophets, our new Saturday series about fascinating people from the past who predicted our current moment and make our world more understandable today.

Last week, we showed how civil rights hero Bayard Rustin predicted the rise of identity politics and affirmative action—and how they would divide us today. Today, Joe Nocera spotlights D.A. Henderson, the epidemiologist who warned that pandemic lockdowns won’t stop a disease, but could instead lead to a public health disaster. Bari Weiss

“In 2006, ten years before his death at the age of 87, the legendary epidemiologist D.A. Henderson laid out a plan for how public health officials should respond to a major influenza pandemic. It was published in a small journal that focused mainly on bioterrorism—and was quickly forgotten.

As it turns out, that paper, titled “Disease Mitigation Measures in the Control of Pandemic Influenza,” was Henderson’s prescient bequest to the future. If we had followed his advice, our country—indeed, our world—could have avoided its disastrous response to Covid.

This month marks the four-year anniversary of lockdowns on a global scale. And though the pandemic has passed, its consequences live on. The lockdowns embraced by the U.S. public-health establishment meant that millions of young people had their education and social development disrupted, or left school for good. Mental health problems rose substantially. So did incidents of domestic violence and overdose deaths.

It didn’t have to be that way.

Last year, Dr. Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health during the pandemic, said at a conference, “If you’re a public health person, you have this narrow view of what the right decision is. . . . you attach infinite value to stopping the disease and saving a life. You attach zero value to whether this actually totally disrupts people’s lives [or] ruins the economy. This is a public health mindset.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief medical adviser to the president during much of the pandemic, was asked in the fall of 2022 whether he regretted his advocacy of lockdowns. He said, “Sometimes when you do draconian things, it has collateral negative consequences. . . on the economy, on the schoolchildren.” But, he added, “the only way to stop something cold in its tracks is to try and shut things down.”

It’s no secret that Fauci’s draconian recommendations did nothing to stop the virus, nor did closing schools save children’s lives. And the idea asserted by Collins and Fauci that public health is about a single metric—stopping a disease, no matter the unintended consequences—was an inversion of the principles espoused by D.A. Henderson.

Public health, as Henderson knew well, is very much about the entire health of society. A lifetime of watching people react to pandemics had taught him two essential things.

First, there were limits to what can be done to stop one. As Dr. Tara O’Toole, a close colleague and one of his three co-authors on that 2006 paper told me, “D.A. kept saying, ‘You have to be practical, and you have to be humble, about what public health can actually do, especially over sustained periods. Society is complicated, and you don’t get to control it.’ ” (While the paper dealt with influenza, its lessons applied to what we faced with the novel coronavirus.)

Second, Henderson believed in targeted protection for the ill and medically vulnerable, and that overreacting, in the form of shutting down society, would bring enormous harm that could be worse than the virus.

In his 2006 paper, Henderson warned public health and political officials of the cascading effects of a shutdown. It is an uncanny description of what took place in 2020:

Closing schools is an example. . . . if this strategy were to be successful, other sites where schoolchildren gather would also have to be closed: daycare centers, cinemas, churches, fast-food stores, malls, and athletic arenas. Many parents would need to stay home from work to care for children, which could result in high rates of absenteeism that could stress critical services, including healthcare. School closures also raise the question of whether certain segments of society would be forced to bear an unfair share of the disease control burden. A significant proportion of children in lower-income families rely on school feeding programs for basic nutrition.

He added:

Political leaders need to understand the likely benefits and the potential consequences of disease mitigation measures, including the possible loss of critical civic services and the possible loss of confidence in government to manage the crisis.

Henderson wrote his paper at an important moment: George W. Bush’s administration was putting together the nation’s first-ever pandemic plan. Those in charge of the effort, viewing Henderson as an old man whose time had passed, didn’t listen. When an actual pandemic arrived 14 years later, the public did indeed lose confidence in the government’s public health experts, just as he had predicted. Today, one can’t help but wonder what that loss of confidence will mean when the inevitable next crisis comes.

How did we get to this sorry state? And what does the late D.A. Henderson, who died of complications from a hip fracture in 2016, just four years before the arrival of Covid-19, have to say about saving ourselves next time?

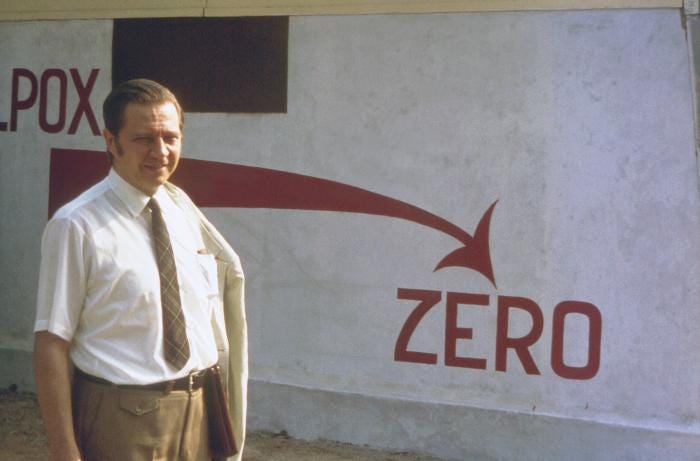

He Did What No One Had Done

He accomplished what was thought to be impossible: the complete eradication of a disease. And not one caused by just any old virus, but smallpox, a terrifying scourge that for millennia had killed, maimed, and disfigured.

He was born Donald Ainslie Henderson in Ohio in 1928. His mother was a nurse, and his father an engineer; from an early age he was known as D.A. After graduating from medical school in 1954, he was offered a chance to join the U.S. Communicable Disease Center—the original name for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC—and he jumped at it. “I decided I was never going to be a practicing doc,” he once said. “It was just too dull, really.”

His boss at the CDC was Dr. Alexander Langmuir, himself a storied epidemiologist who was a fierce believer in what he called “shoe-leather epidemiology.” “This was shorthand for the activities of an epidemiologist who left his office to personally investigate epidemics—collecting data and interviewing patients and officials,” Henderson later wrote in a book about the smallpox effort.

By 1960, Henderson was the head of the CDC’s new disease surveillance department. Smallpox was high on his list of concerns—and for good reason. Ancient, airborne, and highly contagious, smallpox was estimated to have caused around 300 million deaths in the twentieth century alone.

Henderson knew that outbreaks of smallpox were increasing in Europe and, as he later wrote, “I assumed it was only a matter of time before we would have smallpox importations as well.” When the World Health Organization announced a program aimed at eradicating smallpox, Henderson’s superiors at the CDC transferred him to the WHO in 1966 to take charge of what many scientists believed was a futile mission.

An effective smallpox vaccine had been developed in the late eighteenth century; one inoculation conferred lifelong immunity. The problem was that it was simply not feasible to vaccinate the whole world.

Henderson placed doctors and volunteers in all the places where smallpox continued to be a scourge—Africa and India especially. In Nigeria, a doctor he had recruited named William Foege began using a tactic he called “ring vaccination.” Whenever there was a smallpox outbreak in Nigeria, Foege and his staff would race to the infected village, quarantine the infected person, and vaccinate anyone he or she had been in contact with. (We now call this “contact tracing.”) In addition, more effective needles came into widespread use.

The job became the defining event of Henderson’s life. He turned out to be a natural leader, a tall, imposing man with the kind of quiet charisma that inspires others. He was also fearless: Henderson once flew to Moscow to confront the Russians, who were sending his team ineffective smallpox vaccines—in the middle of the Cold War. He was hardly a humble man, but he believed public health should approach its mission with humility. As Dr. Michael Klag, the former dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told The New York Times, “He did not suffer fools gladly, and you were never sure if you were a fool or not.”

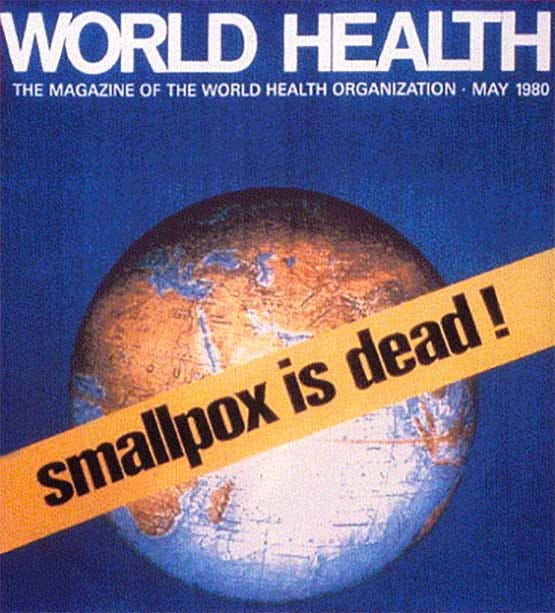

In 1980, after two years without a single recorded case of smallpox, the World Health Organization declared it eradicated. Science writer Richard Preston, who wrote the introduction to Henderson’s book on the effort, described this feat as “arguably the greatest lifesaving achievement in the history of medicine.”

Between 1977 and 1990, Henderson was dean of what was then called the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, but he never stopped worrying about smallpox—or pandemics. Even though the virus was no longer naturally occurring, both the U.S. and Russia retain smallpox stockpiles in case it is needed for research or other purposes. Henderson feared that a terrorist group or rogue nation might get ahold of the smallpox virus and turn it into a devastating bioweapon. In 1998, at the age of 70, Henderson founded a small center within Hopkins—now known as the Center for Health Security—to warn of, and try to prevent, such a possibility.

Green Dots Red Dots

In the new millennium, president George W. Bush began a program to prepare the country for a possible pandemic. This was prompted by the book he brought on vacation in 2005, The Great Influenza, a terrifying account of the 1918 flu pandemic estimated to have killed 50 million people worldwide. Bush had already been caught flat-footed on 9/11. He did not want the government to be unprepared in the case of a killer virus. So he ordered that a plan be devised for responding to such a deadly microbe. “Look,” the president said, “this happens every hundred years. We need a national strategy.”

When a team of government scientists completed the plan two years later, among its central tenets was that schools and other institutions should be closed, and that there should be “reduced contact among adults in the community and the workplace.” This meant lockdowns. This was exactly the opposite of the wisdom about pandemics Henderson had acquired during his long career. He tried to tell them that, but his words fell on deaf ears.

The “science” behind the federal government’s pandemic strategy came, improbably, from a 14-year-old high school student, Laura Glass, who was looking for a science fair project, and who was the daughter of Robert Glass, a senior scientist at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico.

As Michael Lewis tells the story in his 2021 book, The Premonition, Laura was glancing at her father’s computer screen one day as it displayed a simple model. A sea of green dots moved randomly around a few red dots. Any time a green dot collided with a red one, the green dot turned red. In school Laura had been studying the bubonic plague, and while looking at the screen she had one of those eureka moments. She asked her father if his model could be used to show how infectious diseases spread.

Together, father and daughter pursued this idea. Robert Glass found that when he entered different variables on how to stop a respiratory virus from spreading, the most effective way was to close schools—along with other parts of society as necessary. Glass managed to get this model to the two government scientists leading the team developing Bush’s pandemic plan, Dr. Carter Mecher and Dr. Richard Hatchett, who quickly embraced it.

Though none of them were epidemiologists, Mecher, Hatchett, and Glass were convinced that computer modeling would transform epidemiology. In The Premonition, Glass reflected on old-school scientists like Henderson with a kind of pity. “I asked myself, ‘Why didn’t these epidemiologists figure it out?’ ” he told Lewis. “They didn’t figure it out because they didn’t have the tools.” Tools like computer models.

Henderson, on the other hand, believed that basing pandemic mitigation strategies on hypothetical models—models that themselves were based on hypothetical assumptions—could lead policymakers deeply astray. He said that people behaved in unpredictable ways that models could not capture.

A meeting was called in Washington, D.C., in 2006 so that Mecher and Hatchett could present their plan. Scientists from inside and outside the government were invited. Lewis writes that Mecher and Hatchett were alarmed that Henderson was coming, given his doubts about model-based epidemiology.

Indeed, the presentation went poorly, with Henderson and other veteran epidemiologists berating the Bush team for failing to back up their draconian shutdown proposals with real-world evidence, The New York Times later reported. If Henderson was known for not suffering fools gladly, everyone in the room could hear he thought the modelers were fools.

But Mecher and Hatchett stuck by their model, and that was reflected in the pandemic plan, which was published in 2007. Henderson never stopped believing that the path the Bush administration chose was potentially disastrous.

The paper Henderson and his three younger colleagues wrote in 2006, after Henderson’s meeting with Bush’s team, was their last-ditch effort to stop the lockdown plans of the modelers. In retrospect, it was more than a mere journal article. It was a warning about what public health should and shouldn’t do during an outbreak of a highly contagious respiratory illness. It was also a manifesto about the purposes, and limits, of public health.

As he and his co-authors wrote in the 2006 paper:

What computer models cannot incorporate is the effects that various mitigation strategies might have on the behavior of the population and the consequent course of the epidemic. There is simply too little experience to predict how a 21st century population would respond, for example, to the closure of all schools for periods of many weeks to months.

We now know exactly how school closures affected the nation. The answer is very badly.

Consider: among other detrimental consequences, in public schools across the country, chronic absenteeism has risen dramatically since the pandemic. There are also kids who simply gave up; according to one analysis, some 230,000 children in 21 states have disappeared from the school system. In the face of this evidence, the decision by so many U.S. leaders to keep schools closed was an abomination.

And lockdowns didn’t even stop the virus. Here again, the science is irrefutable, with at least 30 studies coming to the same conclusion. As Dr. Michael Osterholm, the prominent University of Minnesota epidemiologist, pointed out to me recently, “Look at what happened in China. They locked down for years, and when they finally relaxed that effort, they had a million deaths in two weeks.”

Then there was the fact that people continued to die of other things besides Covid. The overall death toll in most countries—the so-called “excess death rate”—increased during the pandemic, in no small part because of the medical profession’s narrow focus on Covid patients to the exclusion of everyone else.

Early in the pandemic, in 2020, Sweden was assailed by U.S. public-health experts because of its refusal to lock down its population. One model predicted that Sweden would suffer 82,000 Covid deaths by July 2020. The actual number was 5,455. As for the excess death rate, Sweden’s wound up being one of the lowest in the world—4 percent during 2020 and 2021. The U.S. excess death rate in the same period was 19 percent.

The Lessons

“D.A. Henderson was an absolute giant,” Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, a professor of health policy at Stanford University, told me when I interviewed him for The Big Fail, the book I co-authored with Bethany McLean about America’s dismal response to Covid. One of the lessons Bhattacharya learned from Henderson is that public-health officials can’t just hand down rules and expect them to be followed. Officials, Bhattacharya said, have to “convince people to cooperate so they actually want to do what you are asking.” He added that officials had to understand that there were invariably going to be “knock-on consequences that can cause problems you didn’t anticipate.”

Along with Dr. Martin Kulldorff, who was recently fired by Harvard for his critiques of Covid policy, and Professor Sunetra Gupta of Oxford, Bhattacharya was one of the few scientists willing to publicly criticize lockdowns and other measures government officials were imposing. In October 2020, the three of them co-authored a one-page document, the Great Barrington Declaration, that laid out an alternative response to Covid: protect the elderly and the immunocompromised, and let the rest of society live their lives. “What Dr. Henderson wrote in that 2006 paper is very typical of my understanding of what pre-pandemic planning should be,” Bhattacharya told me.

But instead of embracing, or at least debating, the declaration, Fauci and Collins demonized the three scientists. Federal officials got social media companies to blacklist them. Of course, we now know that the dissidents were right. And now they will get a chance to be heard by the Supreme Court, in a case challenging the federal government’s interference with their right to express their beliefs. Oral arguments are scheduled for Monday, March 18.

But there’s no guarantee officials will make better choices the next time a deadly virus comes our way. If they hope to do their jobs well, a good place to start would be to heed the lessons of D.A. Henderson’s 2006 paper:

Experience has shown that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted.

Joe Nocera is a columnist for The Free Press, and the co-author of The Big Fail. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @opinion_joe. And listen to him talk about our disastrous approach to Covid on the Honestly episode below:

Comments are closed.