Abigail Shrier Was Vilified. Now She’s Been Vindicated.

Some researchers, who at great personal risk challenge the received wisdom of their day, never get the satisfaction of seeing their work vindicated. Fortunately, that hasn’t happened to Abigail Shrier.

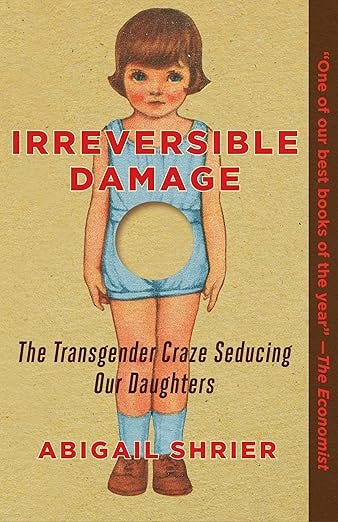

Shrier is the author of the groundbreaking 2020 book, Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters. It is a meticulous, humane, and harrowing account of the sudden and explosive rise in teenage girls declaring themselves to be males. The book is also an examination of a new branch of medicine that has encouraged, and profited from, swiftly putting these distressed girls on powerful hormones, and performing double mastectomies and other surgeries on them.

In working on the book, Shrier found that the claims that daughters could be, and should be, turned into sons was reckless, and that transgender medicine was functioning more like a cult than a scientifically based specialty. The truth of what she revealed has been comprehensively substantiated.

She documented how devastated parents were lied to and coerced. A favorite tactic of gender clinicians was to tell parents that if they didn’t consent to life-altering treatments with a long list of side effects, including sterility, their girls were likely to commit suicide. Parents were routinely asked, “Would you rather have a dead daughter or a live son?”

This kind of rhetoric was not limited to fringe activists pushing an extremist agenda. Over the past decade, it became the standard trope—from human rights organizations, to the legacy press, to the Democratic Party. President Biden himself declared: “Affirming a transgender child’s identity is one of the best things a parent, teacher, or doctor can do to help keep children from harm.” Numerous federal documents encouraged medical intervention.

All this is how the transition of minors came to be seen as a necessity that could not be questioned. Those who dared challenge this orthodoxy risked social and professional ostracism.

Which is exactly what happened to Abigail Shrier.

For exposing what historians will likely judge to be one of the great medical scandals of our time, she was targeted, threatened, and vilified. A typical email to her read, only in part, “. . . I’ll slit your fucking throat and fuck your newly made neck pussy.”

How did she deal with this? Shrier told The Free Press, “I felt I was getting new and helpful information to families in crisis, so I didn’t care who canceled me or what nasty people said on the internet. What concerned me was whether they would be able to disappear the book I had written.”

Her concern was well-founded. Her book was the subject of organized campaigns—some successful—against it.

Before there was even a manuscript, a mainstream publisher who had expressed interest declined to take on the book when the staff threatened a walkout. (Regnery, a conservative publisher, stepped up.) Once it was published, getting it in readers’ hands was a struggle.

Amazon, the country’s largest bookseller, refused to take an ad for the book sponsored by her publisher. Target.com, in response to activist complaints, stopped selling the book. Shrier received leaked internal emails showing a similar boycott was gaining traction at Amazon. In the end, Amazon, along with Barnes & Noble, continued to make it available.

History should also note that some of the individuals and institutions that are supposed to protect our freedom of expression actively tried to suppress Shrier’s work.

Chase Strangio, the co-director of the ACLU’s LGBTQ & HIV Project, and a transgender man, pronounced a kind of epitaph for what the ACLU used to stand for when he tweeted about Irreversible Damage: “stopping the circulation of this book and these ideas is 100% a hill I will die on.”

When the paperback came out in 2021, Shrier’s publisher paid for copies of it to be included in a promotional box of books sent to independent bookstores by the American Booksellers Association. When bookstore employees discovered Irreversible Damage was in the box, hysteria ensued. The ABA immediately tweeted an apology: “This is a serious, violent incident that goes against ABA’s. . . policies, values, and everything we believe and support. It is inexcusable.”

Shrier says few independent bookstores, or even libraries, agreed to carry Irreversible Damage. The controversies backfired to a degree by sparking interest and sales. But the larger lesson is a warning that even in a world awash in information, we live in a time when a few corporations can exercise such control of the national discourse that they effectively end a book’s existence.

But because of Shrier and the work of a handful of brave people—journalists, whistleblowers, clinicians, and detransitioners who are now suing their doctors for damages—we are in a different place than when the book came out four years ago. (Until the last decade, there was virtually no scientific literature on teen girls suddenly developing gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria was almost exclusively male, typically emerging in early childhood.)

A few encouraging developments:

- This month, the UK Health Secretary announced an “indefinite ban” on puberty blockers—a pharmaceutical intervention that prevents normal puberty. He said it was “a scandal” that this intervention was given to “vulnerable young children without the proof that it is safe or effective.”

- England’s Gender Identity Development Service, based in London’s Tavistock clinic, was closed this year after investigations revealed it provided quick medicalization and inadequate mental health care. The Cass Review, commissioned by England’s National Health Service to examine the quality of youth transition medicine, reported this year that “The reality is we have no good evidence on the long-term outcomes of interventions to manage gender-related distress.”

- In 2021, Arkansas became the first U.S. state to restrict youth gender transition. Today, just over half the states do so. The Biden administration and the ACLU brought suit against Tennessee to strike its ban, and in early December the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the case. At that oral argument, in response to questioning by Justice Samuel Alito about the allegedly high rates of suicide among gender-dysphoric youth, Chase Strangio, arguing for the ACLU, essentially blew up the suicide narrative that has been used to frighten so many parents. Strangio told Alito that “completed suicide, thankfully and admittedly, is rare.” (It’s widely expected the justices will decide in Tennessee’s favor.)

- For the most part, the legacy press either demonized, or largely ignored, Shrier’s work. But because she dared to go first, years later it is discovering this scandal for itself. New York Times opinion writer Pamela Paul has published tough pieces about the state of gender medicine. The Washington Post just editorialized about the Tennessee Supreme Court case that the “failure to adequately assess these treatments gives Tennessee reason to worry about them—and legal room to restrict them.”

Still, the risks and dangers Shrier brought to international attention continue to cause harm. In a growing number of Western countries, including the UK, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, their national health services have restricted youth transition. But in the U.S. many of our medical associations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, and the Endocrine Society, have all continued to advocate for youth gender transition on demand.

Taking on this subject, even as a reporter, still comes with tremendous personal risk. Look no further than today’s story in the The Free Press by Jesse Singal, about the death threats he is getting because of his scrupulous work on pediatric gender medicine.

When we asked Shrier where her courage came from, she replied, “That’s not how I think of it. I think of it as having found out something that is wrong, and girls are getting hurt, and my job is to let the public know. That’s the job. If making friends or getting people to like you were the job, I’m not sure I’d be suited to it.

“Saying things that were true was something I was always really willing to do, come what may.”

Comments are closed.