Things Worth Remembering: Winston Churchill’s Christmas Message to America Douglas Murray

https://www.thefp.com/p/douglas-murray-things-worth-remembering-winston-churchill-christmas-message-america

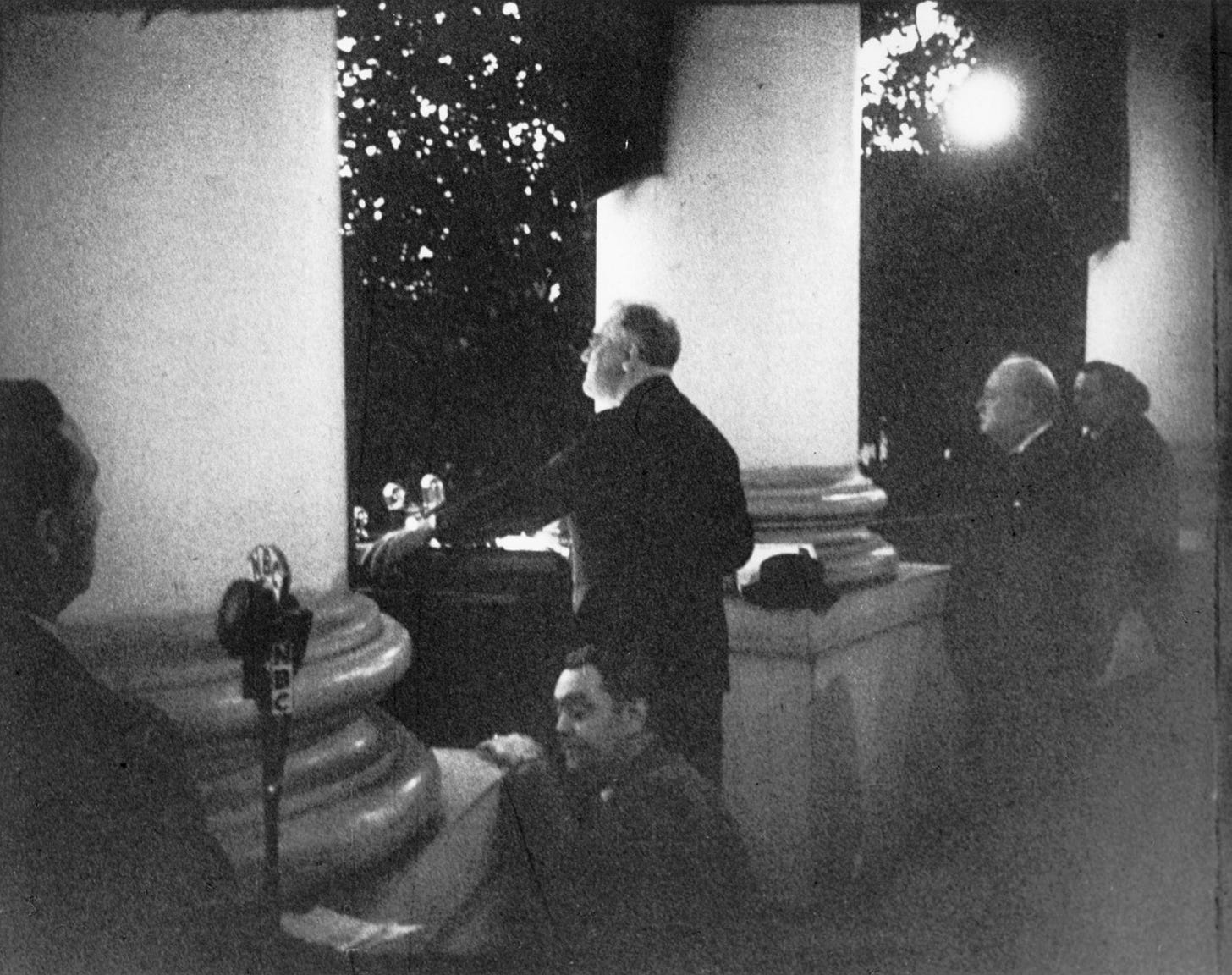

As we near Christmas, I am reminded of the wonderful, 393-word speech delivered by the inimitable Winston Churchill on Christmas Eve of 1941. He spoke from the South Portico of the White House, in the midst of war.

You may recall that I opened the second year of “Things Worth Remembering” with the eulogy given by Churchill on the occasion of his political rival Neville Chamberlain’s funeral, in November 1940.

I am returning to Churchill now because he’s simply the best English-speaking orator of the last century, and because his words and his sense of moral urgency feel especially necessary, as the multipronged war for Western civilization that we find ourselves in grinds on like an acephalous beast. There have been moments in this civilizational struggle—which extends from the Ukrainian forests to the tunnels of Gaza to the Christmas markets of Europe—when I have wondered whether we would prevail. If only, I’ve thought, we had our own Churchill to lead us.

The story behind Churchill’s Christmas Eve speech perfectly captures something essential about the man. Two days earlier, the British prime minister stepped off a plane at an airfield near Washington, D.C., where he was warmly greeted by the American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. “I clasped his strong hand with comfort and pleasure,” Churchill later recalled.

It had been just over two weeks since Imperial Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor, leaving nearly 2,400 Americans dead. Within days, the United States, along with Britain, was officially at war with the Japanese and Nazi Germany.

Churchill’s visit to the United States was meant to be for strategizing: Should the Allies prioritize defeating Japan or Germany? Where should they focus their manpower? And so forth.

But the British prime minister was also keen on solidifying the alliance between the U.S. and Britain, and he obviously wanted to signal to the whole world—starting with Adolf Hitler—that the Western democracies were now united in their mission to crush the Axis.

There was, as always with Churchill, a subtle psychology at work—an awareness of the emotions and competing interests preying on those around him. He had a knack for harnessing those emotions and interests in a constructive way—one, in this case, that might save civilization.

That psychology was on clear display on December 24, when Churchill delivered his Christmas Eve address from the White House, where he and Roosevelt took part in the lighting of the Christmas tree, and delivered remarks to the assembled crowd.

While Churchill’s speech to a joint session of Congress, two days later, is longer, more substantive, and better known than his brief Christmas Eve address, it is the latter in which he really zeroes in on FDR and seeks to deepen their personal bond. This relationship would prove instrumental over the next three-and–a-half years, over the course of the most horrific war the world had ever known, in holding together the Allied powers.

Churchill opened his address by noting that, even though he was far from home, he didn’t feel that way. His mother had been American, he had many American friends, and there was the shared language and shared religion. They were bound together by their pursuit of “the same ideals.”

“I cannot feel myself a stranger here in the center and at the summit of the United States,” he said. “I feel a sense of unity and fraternal association which, added to the kindliness of your welcome, convinces me that I have a right to sit at your fireside and share your Christmas joys.”

It’s important to bear in mind that, by this point, the British had already suffered a great deal at the hands of the Nazis—the London Blitz had started in September 1940 and ended in May 1941—and they understood, in ways that perhaps the Americans could not, what lay ahead. Churchill, especially, grasped how much blood would have to be shed, and he worried that FDR did not—and that the Americans might lose the will to fight.

Churchill then pivoted, as he sought to link the warmth and love of Christmas with the war that Britain and the United States were now fighting.

“Ill would it be for us this Christmastide if we were not sure that no greed for the land or wealth of any other people, no vulgar ambition, no morbid lust for material gain at the expense of others, had led us to the field,” he said.

No, the reason that these two nations now found themselves at war, the reason he was there, in the White House, on this “strange Christmas Eve,” was that this war was not like any other that had ever been fought. It had been started by monsters fueled by maniacal visions of worldwide domination, and it would be ended—if Churchill had his way—by him and the man in the wheelchair next to him. (He could not have known, at the time, that FDR would die in April 1945, just before the Germans and then the Japanese surrendered.)

It was critical that everyone, especially Roosevelt, understood this: Their war was not, as Churchill put it, about “greed” or “vulgar ambition.” It was about protecting the love, the beauty, of Christmas from those who would do away with it, strip it of its meaning, its charity, its enduring value.

“Here, in the midst of war, raging and roaring over all the lands and seas, creeping nearer to our hearts and homes, here, amid all the tumult, we have tonight the peace of the spirit in each cottage home and in every generous heart,” Churchill went on.

He was painfully aware that, for many young men eagerly signing up to defend their country, this would be their last Christmas.

“Therefore we may cast aside for this night at least the cares and dangers which beset us, and make for the children an evening of happiness in a world of storm,” Churchill said. “Here, then, for one night only, each home throughout the English-speaking world should be a brightly-lighted island of happiness and peace.”

Today, it is much harder to make out the contours of the conflict we are fighting than it was in December 1941. We have not declared war. No one has explicitly said they want to fight with us. Our enemies are dispersed across a global, loosely fitted-together network; they do not quite amount to an Axis the way the Germans and Japanese once did.

And yet, we feel that the nation is under fire. As is America’s military superiority and soft power, and the values that young Americans have long been steeped in: God, country, freedom. That is why Churchill’s words are worth remembering.

“Let us grown-ups share to the full in their unstinted pleasures before we turn again to the stern task and the formidable years that lie before us,” Churchill said. “Resolved that, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance or denied their right to live in a free and decent world.”

Click below to listen to Douglas reflect on Churchill’s Christmas Eve message:

Comments are closed.