Will NIH Cuts Boost Public Health—or Destroy It?By David Andorsky and Vinay Prasad

https://www.thefp.com/p/trump-nih-cuts-debate?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Two cancer doctors debate whether Trump’s slashing of billions to the National Institutes for Health will boost public health or destroy it.

During his testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions hearing on Wednesday, Jay Bhattacharya, President Donald Trump’s nominee to run the National Institutes of Health, seemed to side with the president’s plan to cut billions of dollars from the nation’s scientific research budget, most of which is controlled by the NIH.

“I have a background as an economist as well as being a doctor,” Bhattacharya told the committee. This helps him “understand that every dollar wasted on a frivolous study is a dollar not spent. Every dollar wasted on administrative costs that are not needed is a dollar not spent on research. The team I’m going to put together is going to be hyper-focused to make sure that the portfolio of grants that the NIH funds is devoted to the chronic disease problems of this country.”

Some of Trump’s cuts have already been made, including the firing of over 1,000 “probationary” workers, and the blocking of this year’s grants through a bureaucratic loophole. The Trump administration also wants to stop paying indirect costs for building space, expensive equipment, and oversight of medical research, though so far that has been stopped by a judge’s temporary order.

What should we make of these cuts? Are they a sensible way to make medical research even more efficient? Or will they threaten the development of cures that could save millions of lives?

We asked two oncologists we trust to debate this important issue.

David Andorsky is an oncologist in private practice who believes that these cuts will be disastrous. “I spend my days with patients who’ve been saved by miraculous treatments that were invented by scientists working at labs, primarily academic ones, funded by the NIH,” he said.

Vinay Prasad, a frequent contributor to our pages, is also an oncologist as well as a professor at the University of California, San Francisco. But he has a different view—that paring back the NIH’s research budget can be healthy, forcing the agency to make better choices about what it should, and should not, fund.

Here are David and Vinay:

David Andorsky: Vinay, I have a lot of respect for you—I’ve listened to your podcast and heard a talk you gave for the U.S. Oncology Network a few years ago. But I can’t imagine another oncologist saying that these sorts of sledgehammer research funding cuts are a good thing. My perspective comes from my own experience as a clinician. I spend my days with patients who’ve been saved by miraculous treatments that were invented by scientists working at labs, primarily academic ones, funded by the NIH. I see patients every day who would be dead without these medical advances.

We can quibble about whether the NIH could be more efficient. But the cuts proposed by the Trump administration would create budget deficits of many millions of dollars at every medical research institution in the country.

Vinay Prasad: David, thanks for coming to that talk. Just to clarify my position: I support Trump’s proposal to cut indirect costs. When the NIH gives a grant to universities, it pays some money directly to researchers and their teams, and some to the university as overhead or indirect.

Currently, if a researcher gets $100,000—the university can get an additional $50,000 or $65,000, or even $90,000—that is the indirect. At some places like Salk and Scripps, two research institutes, indirect rates are up to 90 percent. Trump has proposed capping indirects at 15 percent.

Indirect costs don’t go to researchers, they go to universities, often the dean, and are unaccounted for—some of these funds support mandatory trainings and a vast administrative state.

I agree that NIH dollars have led to the science underpinning many successful cancer drugs. I might dispute a widely used 99.4 percent figure, but I think 40 to 80 percent is quite plausible. Yet, to me, the current NIH is like a farm. It is 100 acres and grows tomatoes. Last year, it grew 200 tomatoes. I have no doubt it grows tomatoes, but why can’t it grow two tons of tomatoes? It is inefficient and wasteful. The current system is overrun with poor incentives, endless bureaucracy, and mismanagement. It surely needs reform.

DA: Slashing indirect funds is wielding a sledgehammer where a scalpel would be more appropriate. To use your tomato farm analogy, it’s as if I run a farm where I receive $100,000 in private investment funding to run the farm, and the next year, I’m told that I will only get $50,000. With a slash like that, not only will I not be able to make two tons of tomatoes, I’ll be lucky to make the same 200 I made last year. Maybe I’ll even go out of business.

The indirect costs go to fund essential infrastructure that supports medical research, such as the laboratory space, expensive equipment shared by labs, and oversight boards that make sure research is conducted safely and with integrity. The separation between “direct” and “indirect” costs is a distinction without a difference—the bottom line is that federal funding for biomedical research is being cut by $4 billion, full stop. You characterize this as a “small place to start,” but from the perspective of the researcher, it’s anything but small. Every academic biomedical scientist I know is worrying about when their grants are going to get reviewed, how they are going to afford to conduct their research, if they can afford to bring on new graduate students, the next generation of researchers-in-training.

VP: Of course, some indirect money is used for labs and benches, but much of it is used for things the American people would not approve of. Some of it is spent on mandatory training modules, or to fund lavish events with business-class travel and alcohol. Moreover, the money has been used to grow universities in behemoth administrative states. I think the taxpayer deserves to know that each dollar we are spending on growing tomatoes is used to grow as many tomatoes as possible, and the current NIH system is far from that.

I am not sure if indirects should be at Trump’s proposal of 15 percent, but I think, like so many Trump actions, it is a starting point for negotiation, and much better than 65 percent.

DA: This makes no sense to me. Every dollar the NIH spends on biomedical research is estimated to yield over $2.46 in economic activity. Most of the new classes of drugs I use to treat my patients had their origin in basic research funded by the NIH. Scientists come from around the world to study in American labs—do we really want tomorrow’s American scientists to have to go to China to work in the world’s best labs? The American biomedical research establishment is the envy of the world. If we want to put “America first,” I don’t see why the Trump administration wants to jeopardize all of that to save what, in the end, is a small amount of money in the scope of the federal budget.

VP: Part of the reason we see this differently is that we disagree about the specific policy that the Trump administration has proposed. Let us imagine the NIH has $10 million to give. Let’s also stipulate the indirect cost rate is 60 percent, which is on par with many universities.

One hundred scientists who work at universities apply for those $10 million; each wants $1 million for their laboratory. They submit lengthy proposals that take a lot of their time to write. Surveys suggest that many researchers spend the majority of their time writing these grants. After months of peer review, the proposals are scored.

With $10 million, only the top six people get a million dollars in grant funding. That’s $6 million. Their institutions—the university, usually the dean’s office—gets $3.9 million dollars for overhead or indirects. The researchers typically don’t get this money. Although they say the money is for the lights and lab materials, some of these proposals don’t require much lab space. For instance, computation and epidemiologic research—what my lab does—doesn’t.

Now, under the Trump proposal, what happens to that same $10 million? The top eight labs would get a million dollars each, and their universities get $1.2 million. Two labs that weren’t going to be funded—now are. I would not call this shift a “sledgehammer.” In fact, it sounds good to me, and is precisely how the Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg [Initiative] give out their money.

Some have argued that the NIH isn’t going to fund more labs, but I disagree with this interpretation. Congress has already appropriated the funds, and I am confident that Jay Bhattacharya wants to fund more science. I also suspect he wants to fund less administration.

DA: Let me give you an example of NIH funding that works: the development of chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T). Decades of laborious basic science at the NIH in cancer immunology finally led to the advent of CAR-T, in which a patient’s own immune cells are reprogrammed to fight cancer. In a groundbreaking paper published in 2013, scientists at the University of Pennsylvania reported the cases of two girls with refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia who had a miraculous recovery from their illness due to this treatment. This study was largely funded by multiyear R01 NIH grants—exactly the sort of grants that Trump’s administration is holding up right now. CAR-T has now been commercialized by dozens of pharma companies and FDA-approved for use in an ever-expanding number of malignancies. I know you are critical of NIH funding as being too conservative or not daring enough, but at least in oncology, I would argue that’s not the case—the CAR-T story being a good example.

VP: CAR-T is an interesting story where NIH-funded research yielded a successful product. I agree with David that this would not have occurred without NIH funding. Despite that funding, those cures are priced ten to twentyfold higher than manufacturing costs, and largely taken by pharma, and currently, just 3.9 percent of U.S. cancer patients are eligible for CAR-T. Notably, not all patients are cured. In multiple myeloma, for instance, 100 percent of patients will have their cancer recur. I don’t disagree that the NIH has led to good and useful medical products—again, I suspect 40 percent to 80 percent of all drugs. Again, the farm does grow tomatoes, but my concern is that the system is wasteful, not optimized, and gives too much to administrators in the process.

DA: The only way to understand the Trump administration’s actions here, in my view, is either as a concerted effort to destroy federal funding of biomedical research, or to place such a high value on rooting out all traces of “wokeism” or “gender ideology” from biomedical research that it is willing to bring the entire operation to a halt in the service of its own ideological agenda. The vast majority of biomedical research has nothing to do with these hot-button topics, but they are caught up in the dragnet. It’s hard to imagine that killing tomorrow’s cures is what the American people voted for in the last election.

VP: Yes, to your point, I think they don’t want to fund woke science—science that just documents racial disparities without proposing solutions, science on gender and the like. Instead, I suspect Jay would want to fund economically rigorous basic discovery.

And, in fairness, I agree that as a result of this change some of these eight labs will have to more carefully construct their budgets. They might have to include direct fees for some resources that were previously covered under indirects. They need better bookkeeping. But there are now two labs who actually get to do science who previously weren’t.

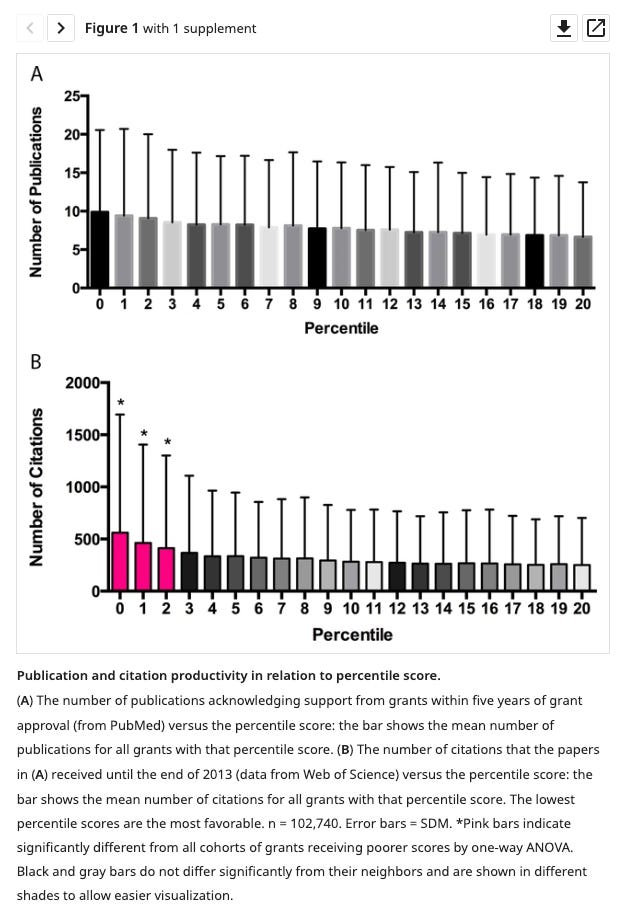

One question you might have is: Wait, instead of funding the six best labs, we now fund the eight best? But what if those extra two labs are not nearly as good as the first six? That’s a good question that has an answer. Prior work has shown that the ranking and the productivity of labs have nearly nothing to do with each other. Here is a graph from a paper on this topic:

It shows that moving from six funded projects to eight funded projects means we aren’t selecting two inferior projects, but two projects that are probably nearly just as good as the first six! I believe that science is often serendipitous, and, as such, we don’t know how many breakthroughs we miss out by funding six instead of eight.

This is what Trump’s proposal means—less indirects, more grants—and I worry the media coverage of it has been almost intentionally malicious. Many people, including Obama, have contemplated cutting indirects and setting a flat rate without sweetheart deals for some universities in the past.

Are researchers worried? I agree with you that they are, but they have been hyperbolic in my opinion, and many of them, perhaps most, would be hysterical about anything Trump does. That has been the case for the last decade, and been counterproductive. I think 15 percent is a useful starting point for discussion. Universities, particularly the leadership, should worry. They are suing in court and litigating this among public opinion with the narrative Trump is killing cures, but I think this time it will backfire. The public is so fed up with higher education, they have lost sympathy. Elsewhere I suggest they should hold policy debates.

Finally, I want to raise the thorny issue of just how much the NIH funds that is neither true nor useful. Over the last decade, we have had several teams take science papers from the top journals and try to replicate or reproduce the main finding. One project found only 40 percent can replicate. The other two found 11 percent or 25 percent replicate.

Why is it so low? Because, despite creating a huge administrative state and having endless review, the process is broken. If a lab runs an experiment eight times, it might just report the two most favorable results. If a researcher runs a model 10 ways, she may just present the two versions with the favorable result. It is cherry-picking on an industrial scale.

Some labs—even high profile ones at Harvard and Stanford—were found to or strongly suspected to have committed fraud. When fraud is found, often it is swept under the rug. In the case of fraudulent work from Harvard, I am not aware of a single lab head being punished as a result. That’s the current NIH culture. Spending taxpayer money on work that cannot replicate, with no accountability for fraud.

DA: I wish that DOGE was really interested in making biomedical research more efficient—if, as you suggest, they want to fund eight labs instead of six. I see no indication that this is the case. I think the goal here is to shrink the pie, not to distribute it better. Many Republican lawmakers favor getting rid of the federal grant review process altogether and distributing the funds to the states as block grants to use for biomedical research by their universities. Can you imagine anything less efficient? That every state would have to convene its own review committees to fund research, thus duplicating the same work 50 times over? It’s completely ludicrous, and I think it gives away the game that we are not talking about efficiency or quality here, we are just talking about less government funding for medical research.

Another question that gets asked is, Why can’t pharma fund this research? It’s because private companies aren’t set up to provide seed funding that may lead to a marketable product in 15 to 20 years. They need to see profits sooner than that. Only a federal agency with a mandate to improve the health of Americans will have the patience to fund this kind of research. Pharma will take an idea and run with it once it appears that it’s likely to work. But real breakthroughs require an interest in looking at very basic mechanisms of human biology.

There are many ways I could think of for the NIH to address research fraud—for instance, sanctioning organizations that have failed to discipline scientists guilty of fraud, or requiring a certain amount of replication in order to fund the next phase of a project, and so on. But just slashing funding is not going to get us there. It’s just going to result in less research being done, without improving quality.

There are many people cheering the “disruptive” nature of what DOGE is doing. But the NIH is not Twitter. If Elon Musk wants to break Twitter, go ahead, the world can live without it. I don’t think any of us want to live in a world where biomedical research in the U.S. grinds to a halt.

VP: Much of the rhetoric here is based on the idea that each additional dollar leads to an equal chance of a cure. With that framework, I am curious what David thinks the U.S. should spend on the NIH annually? Why stop at $47 billion? Why not $100 billion a year, $200 billion, $400 billion? The reality is that the relationship between money and cures, and precisely who gets the money, how universities manage it, and how science is incentivized is far more complicated. There is likely some diminishing return on investment, and the $47 billion we spend could already be utilized so much better.

Finally, NIH-funded research has led to cures, but also some errors. It might have, for instance, led to the global pandemic that cost $20 trillion and 20 million lives, busting the $1 to $2 ratio.

DA: I agree this is getting long, but a few final points:

DOGE has cut billions of dollars across the government, and it has not redirected those dollars—it has just said that it won’t spend them. The Trump administration believes that it has the right not to spend money appropriated by Congress, and it has argued so in court. There is no reason to believe that NIH funding will be treated otherwise.

I agree it’s not right that pharma charges 10 to 20 times the cost of manufacture for CAR-T (and other cancer therapeutics) when the intellectual property for those treatments relies on NIH-funded research. Maybe the government should demand royalties. I would support that.

In an ideal world, we would spend more than $47 billion on federally funded medical research, because every dollar does deliver a good investment on behalf of the American people. The $47 billion is based on finite resources and political compromise at the Congressional level, as is every other line item in the federal budget.

Finally, if you truly believe that the NIH bears responsibility for creating Covid-19, just say it, instead of insinuating that it “might” have. (To be clear: I completely disagree with that assertion.) On the flip side, it is clear that NIH-funded basic virology research set the stage for the development of a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine less than nine months after the pandemic started—a remarkable achievement, one that clearly saved millions of lives, and one that we should all celebrate as a success of the U.S. scientific establishment.

VP: Since David went first, perhaps I can go last. One proposal Jay Bhattacharya is reportedly considering is tying NIH grants to institutions’ commitment to academic freedom. Famously, Jay and colleagues were pressured by Stanford leadership to stop speaking critically of Covid policy. During the pandemic, universities widely failed to foster debate and discussion, and ceded this territory to podcasters. The indirects represent public money, which in part has been used to prop up the administration of universities, who are now under fire for their handling of pandemic debates as well as the Middle East protests and other social and political issues.

In many ways, universities and academic medical centers brought reforms down on themselves. Their leadership forfeited public confidence, which has set the stage for long-overdue reforms to the study sections, indirect rates, and surely more to come.

Comments are closed.