How America’s Accurate Election Polls Were Covered Up The Real Clear Politics National Average was removed by Wikipedia before the election and the New York Times denounced its failure to skew data. A solution to the “mystery” of crappy polling? Matt Taibbi

https://www.racket.news/p/how-americas-accurate-election-polls

John McIntyre couldn’t believe it. The publisher of the Real Clear Polling National Average, America’s first presidential poll aggregator, woke on October 31st to see his product denounced in the New York Times. Launched in 2002 and long a mainstay of campaign writers and news consumers alike, the RCP average, he learned, was part of a “torrent” of partisan rubbish being “weaponized” to “deflate Democrats’ enthusiasm” and “undermine faith in the entire system.”

“They actually wrote that our problem was we didn’t weight results,” says an incredulous McIntyre. “That we didn’t put a thumb on the scale.”

The Times ended its screed against RCP’s “scarlet-dominated” electoral map projection by quoting John Anzalone, Joe Biden’s former chief pollster, who said: “There’s a ton of garbage polls out there.” But being called “garbage” in America’s paper of record was nothing compared to what happened to RCP at Wikipedia.

Six months ago, when former Wikipedia chief Katherine Maher became CEO of NPR, video emerged of her talking about strategies at Wikipedia. She said the company eventually abandoned its “free and open” mantra when she realized “this radical openness… did not end up living into the intentionality of what openness can be.” Free and open “recapitulated” too many of the same “power structures,” resulting in too much emphasis on the “Western canon,” the “written tradition,” and “this white male, Westernized construct around who matters.”

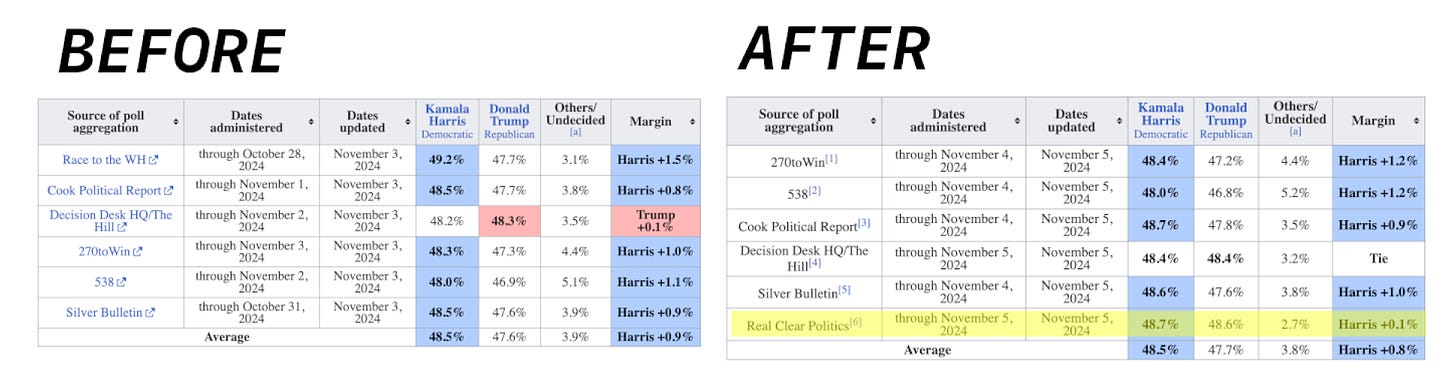

In the context of poll averages, it seems even a track record of accuracy did not “end up living into the intentionality of what openness can be.” The ostensibly crowdsourced online encyclopedia kept a high-profile page, “Nationwide opinion polling for the 2024 United States presidential election,” which showed an EZ-access chart with results from all the major aggregators, from 270toWin to Silver’s old 538 site to Silver’s new “Silver Bulletin.”

Every major aggregate, that is, but RCP. McIntyre’s site was removed on October 11th, after Wikipedia editors decided it had a “strong Republican bias” that made it “suspect,” even though it didn’t conduct any polls itself, merely listing surveys and averaging them. One editor snootily insisted, “Pollsters should have a pretty spotless reputation. I say leave them out.” After last week’s election, when RCP for the third presidential cycle in a row proved among the most accurate of the averages, Wikipedia quietly restored RCP.

“They just whitewashed us away three weeks before the election because we were a point or a point and a half more favorable to Trump, which as it turns out still underestimated him,” McIntyre said.

What happened in 2024 to RCP is emblematic of wider failures in data journalism, which has now turned in three straight cycles of obscene misses. Although problems in polling have been lavishly, even excessively covered, failures are inevitably presented as a Scooby-Doo whodunit, rooted in a magic invisibility power apparently unique to Trump voters. “If Trump outperforms the polls once again,” the Atlantic concluded this August, “something about his supporters remains a mystery.”

But it’s no mystery. The polling problem in America looks like good-old-fashioned lying, mixed with dollops of censorship and manipulation:

Start with a basic fact: major aggregators like 270toWin, Silver Bulletin, 538, and the Cook Political Report, while useful, are not the uncomplicated averages many customers imagine them to be. “A poll average is simple,” says McIntyre. “You add polls up, and you divide by the number.”

But the “reputable” or “nonpartisan” averages are different. “Those are really models, but they don’t call them that,” McIntyre says. “The New York Times had an average and the Washington Post had one, but they’re not really averages. They’re more like, ‘This is where we want to say the race is.’”

Most “averages” or “aggregates” have pages that explain how they weight results, though the exact recipe is usually a mystery. The Times in September explained in a general way how it weights pollsters. To an unspecified degree it favors track records of “unbiased and accurate results” (note the term “accurate” isn’t by itself). It also upgrades for “professionalism,” which to the Times among other things means an average that “contributes microdata” to Cornell’s Roper Center or is a member of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

The real devil is in this detail:

Partisanship. A poll receives less weight if it’s sponsored by partisans or a campaign.

What does “partisan” mean? The Washington Post proscribes polls that are “paid for by candidates or partisan groups,” and certain agencies are bounced from some aggregates because they have reputations as right-leaning, like Rasmussen and Trafalgar. Other polls are often dismissed as “low-quality,” like Emerson or Insider Advantage. But herein lies the rub: the “low-quality” polls have often outperformed the “high quality” ones of late, particularly in elections involving Trump.

“High quality polls are accurate polls,” says McIntyre.

“Many polls that have traditionally been more accurate struggled in 2016, 2020 and 2024,” says Nate Silver. “They were better — indeed, pretty good — in the two midterms (2018, 2022). But they can’t seem to capture enough Trump supporters, probably because they’re less likely to respond to surveys.”

Much as there’s been a boom of independent news on places like Substack, there’s been a proliferation of new polls, some with iffy methodologies, competing with the traditional names. It’s this group that legacy outlets like the Times accuse Republicans and third-party candidates of using to “flood the zone” with inaccurate information. But mainstream aggregates are opaque in their own ways, and can tinker with weighting formulas to make a candidate’s outlook look sunnier than it is. Though this surely happens, manipulation accusations tend to run in one direction, and RCP is the only average to deal with anything like a deplatforming.

Because it appeared on the scene years before Mark Blumenthal’s Pollster.com (2006) and Silver’s original FiveThirtyEight (2008), the Real Clear average has a long tradition of use by reporters; MediaShift in 2008 called RCP the “ultimate political aggregator.” But the Times in 2020 wrote a piece skewering it for a “hard right turn,” saying it “seemed skewed by polls that have been ‘a bit kinder to Trump.’” This year’s Times piece was even more harsh. As evidence that its “incentive is not necessarily to get things right,” as one of the paper’s sources put it, the Times cited RCP’s “No Tossups” map, which “currently shows [Donald] Trump winning every swing state,” as if this were inherently absurd.

“It was put out on Halloween, the week before the election,” McIntyre says. “They said, ‘Yeah, they had this crazy map that shows Trump winning all swing states.”

It was a double error by the Times. RCP in fact only had Trump winning 5 of 7 swing states (which they ended up noting in a correction), but a sweep would have been more accurate, not less.

The Times is one of many outlets that weights against “partisan” or “low-quality” polls, really a synonym for “Republican-friendly.” But there’s no similar downgrading of polls conducted by CNN or the Washington Post or New York Times/Siena, despite similarly obvious editorial partisanship. This is particularly bizarre given what happened in the 2020 presidential race, in which “reputable” polls overestimated Joe Biden’s vote by 4.5-5 percentage points, the industry’s worst performance in 40 years. The Washington Post’s bizarre stretch-run poll showing Biden with a 17-point lead in Wisconsin was a major factor in queering national aggregates (Biden actually ended up winning the state by less than a point).

McIntrye compared the 17-point Post Wisconsin poll in 2020 to a scene from Season 2 of Narcos, supposedly based on a true story. Although the long-entrenched PRI in Mexico was likely to lose, faked news of exit polls showing clear victory was put out early, depressing enthusiasm.

“We’re not going to actually rig any votes, but we’re going to release this fraudulent exit poll showing the PRI winning,” McIntyre says. “There’s no question that the polling, if it’s not honest, becomes an information weapon. If Wisconsin’s truly a swing state and the guy’s up 17 points, you think, ‘Well, I guess it’s not close.’”

Ironically, this is what the Times accused RCP and others of doing heading into last week’s vote:

The torrent of polls began arriving just a few weeks ago, one after the other, most showing a victory for Donald J. Trump… They stood out amid the hundreds of others indicating a dead heat… But they had something in common: They were commissioned by right-leaning groups… These surveys have had marginal, if any, impact on polling averages, which either do not include the partisan polls or give them little weight… some argue that the real purpose of partisan polls… is directed at… building a narrative of unstoppable momentum for Mr. Trump.

Times authors Ken Bensinger and Kaleigh Rogers, who didn’t respond to requests for comment, told on themselves in that text a little. While the “partisan” surveys showing a Trump win were dropped or weighted down to have “little impact,” a long list of cheery “nonpartisan” results did work their way into “reputable” averages. A Dartmouth poll on the week of the election, for instance, showed Harris winning New Hampshire by 28 points. Other mainstream averages showed consistently over-optimistic results in places like Michigan, which was explicable only if you declared all but the rosiest polls to be “low quality.”

Silver believes the “polling beat has gotten better and is generally on the more rigorous side of what these news organizations do..” But is there a built-in slant to how all of this is described in mainstream coverage? “As someone who generally thinks implicit bias is a Thing and there’s an uncomfortably blurry line between the partisan and nonpartisan roles that the MSM plays, then sure.”

For McIntyre, this was frustrating because he felt he was being punished for not kissing the statistical behind of big-name media outlets. “If we use a pollster and it’s in our timeline, we put it in our average and we don’t weight it,” he says. “So the New York Times gets the same weight as a Trafalgar or an Insider Advantage, or new polling from Atlas… But the Times writes a hit piece because we’re using these polls that they effectively weight away to nothing.”

It was bad enough the Times dinged RCP for failing to use the same weighting process papers like themselves or the Washington Post employed. But Wikipedia’s decision to remove RCP speaks to a hairier problem with how the Internet weighs “authority” or “reliability.” Search engines like Google and sites like Wikipedia (to say nothing of fact-checking outfits like PolitiFact) rely so much on corporate name recognition that stories remain invisible if mainstream outlets decide not to touch them. In the same way Wikipedia’s Twitter Files page relied on skeptical mainstream accounts, obscuring source material, the removal of RCP essentially made polls favorable to Trump hard to detect this campaign season, even though they were more accurate. This is part of what made the election cathartic for some: it was a result that for once didn’t rely on snobbish panels of judges, but a mass vote.

How many more processes need to be “de-weighted”?

The list of surveys from the last two months of the campaign were full of swing state polls from outlets like CNN or Times/Siena showing Harris up five or six points in key battlegrounds.

Comments are closed.