How Social Media Pushes Vulnerable Teens Toward Eating Disorders Social media companies must take more responsibility to address how their products are fueling adolescent eating disorders Kristina Lerman

Introduction from Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch:

In Chapter 6 of The Anxious Generation, we examined the connections between social media use and adolescent mental illness, with a focus on depression and anxiety. We outlined six reasons why social media harms girls more than boys: (1) girls spend more time on visual social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok; (2) they have a heightened vulnerability to visual social comparisons; (3) relational aggression is more prevalent among girls; (4) girls face greater pressures toward perfectionism; (5) they are more susceptible to the interpersonal spread of emotion; and (6) they encounter an increased risk of sexual harassment and online predation.

Throughout the book, we focused on anxiety and depression as the main categories of mental illness for which we found clear evidence of harm from heavy social media use. We mentioned eating disorders just a few times, especially in the story of Alexis Spence. But if you look at the list we just gave of six ways that social media affects girls, you can see that there may be multiple channels through which social media can push girls into eating disorders (some of which are classified as anxiety disorders).

We’ve been meaning to learn more and say more about links between social media and eating disorders. We were pleased, therefore, when Morteza Dehghani—a friend of Jon’s at the University of Southern California—introduced us to his colleague Kristina Lerman, who had just written a paper on the topic. Kristina is a Research Professor in the USC Computer Science Department, and she is a Senior Principal Scientist at the USC Information Sciences Institute. She was trained as a physicist, and she now uses her quantitative skills to study networks, crowdsourcing, and patterns in large datasets derived from social media activity.

Her recent paper is titled “Safe Spaces or Toxic Places? Content Moderation and Social Dynamics of Online Eating Disorder Communities.” Written with four colleagues, it is currently under review at EPJ Data Science, and you can read it online here.

The study compares online discussions about eating disorders on Twitter/X, Reddit, and TikTok, finding that while users on all platforms seek support in similar ways, platforms with less stringent moderation (particularly Twitter/X) foster toxic echo chambers that amplify pro-anorexia rhetoric. In contrast, stronger moderation appears to reduce the spread of this kind of content, although it is still there, just somewhat more hidden. We just searched for a few common keywords (#thinspo, #bonespo, #deathspo) on X. We immediately found a great deal of horrific pro-ana content. We think that Kristina’s research is essential for parents, teens, and legislators to better understand, so we invited her to write a less academic summary of her work for our readers at After Babel.

Kristina’s findings demonstrate the urgent need for design changes on social media platforms, and for raising the age for opening social media accounts to 16, which would be the most reliable way to reduce the degree to which younger teens are immersed in pro-anorexia content and toxic echo chambers.

”

Grace is the daughter of a close family friend (though I am not using her real name). Like so many teens stuck at home during the pandemic, Grace noticed she’d gained a few pounds. Feeling self-conscious, she did what countless others did: she turned to social media for tips on “losing weight” and getting “healthier.” What began as innocent searches quickly filled her feed with a constant stream of “thinspiration” posts and extreme dieting advice. In these online spaces, anorexia wasn’t treated as a dangerous illness—it was glorified as a lifestyle. Users encouraged one another to eat less, exercise more, and hide it from friends and family. Before long, Grace was counting calories, skipping meals, and obsessively tracking her steps—losing weight, yet never feeling thin enough. When schools reopened for in-person learning, Grace didn’t return to class. Instead, she entered a residential treatment center for anorexia.

Stories like Grace’s have played out across the U.S. for years, contributing to the steady rise of eating disorders (EDs). EDs represent a cluster of complex mental health conditions like anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder and are defined by obsessive thoughts and harmful behaviors around food, eating, and body image. They rank among the deadliest mental health disorders, second only to opioid addiction. Between 2000 and 2018, the prevalence of EDs in the general population worldwide doubled from 3.4% to 7.8% and among children and adolescents in the U.S., health visits related to EDs also doubled from 50K in 2018 to more than 100K in 2022.

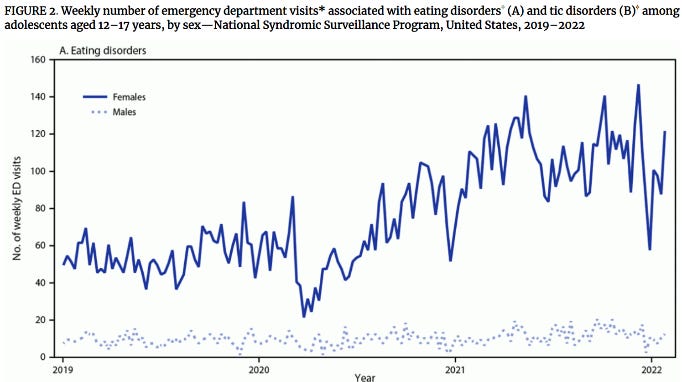

While eating disorders have historically been more common among girls and young women the gender gap widened dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to theCDC, emergency department visits for eating disorders among adolescent girls more than doubled during the pandemic, while boys were unaffected (Fig. 1). The reasons behind the gender gap arestill debated, butdifferences in how teens spent their time online may be part of the story. While boys often turned to video games, where matchmaking algorithms pair players of similar skill levels to keep games competitive and fun, girls spent hours on social media—where recommendation algorithms stack their feeds with toxic influencer content, triggering a downward spiral of negative self-comparison.

Figure 1: Pediatric Emergency Department Visits Associated with Eating Disorders Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic, January 2019–January 2022 (Source: CDC)

Eating disorders provide a lens for understanding social media’s role in amplifying psychological distress. In the rest of this post, I examine mounting evidence suggesting that social media damages body image—especially for girls and young women. I describe how algorithms and peer interactions within online communities can systematically guide vulnerable users toward more extreme disordered thought patterns and eating behaviors. Enforcing a minimum age of 16 in addition to targeted content moderation is essential to disrupt these dangerous radicalization dynamics that can trap users in harmful echo chambers. Without effective age verification and moderation, social media platforms risk continuing to expose vulnerable youth to extreme content that normalizes and potentially accelerates eating disorder development and progression.

The “Thin Ideal” and Body Dissatisfaction

Experts have linked eating disorders to the proliferation of idealized body images in the media (Harriger et al., 2022). Exposure to the “thin ideal” fosters negative self-comparisons and pressure to meet unrealistic beauty standards—key risk factors for developing body dissatisfaction and subsequently, eating disorders. One striking study showed that before the introduction of western TV programming in Fiji, purging behavior as a way to control weight was virtually unknown. Afterwards, purging, which is a hallmark of bulimia, rose to affect 45% of girls. Social media companies are aware of this toxic connection. Internal documents from Facebook leaked by the whistleblower Frances Haugen (the “Facebook Files“) revealed that the company knew its platforms, particularly Instagram, negatively affected women’s and girls’ body image. These documents showed that 60% of Instagram’s female users and 46% of male users reported frequent body dissatisfaction, with the negative impact especially pronounced for teen girls—1 in 3 reporting that using Instagram leaves them feeling worse about their bodies.

Facebook’s own research on Instagram’s impact identified specific triggers that worsened body image: content with high engagement metrics, attractive profiles, approving comments on others’ photos, and content from “middle rung” friends—those closer than acquaintances but not intimate connections. Such content created what researchers described as a “downward spiral” leading to serious mental health consequences, including eating disorders, depression, and body dysmorphia.

Beyond Exposure: Peer Radicalization in Pro-ED Communities

However, social media’s pernicious effects extend beyond mere exposure to unattainable beauty standards. The relationship is driven by the algorithmic and social dynamics of online platforms. Recommendation algorithms may systematically direct vulnerable individuals searching for weight loss or fitness advice toward more extreme content promoting dangerous dieting and excessive exercise. Beyond static advice, users encounter online communities or influencers who reframe eating disorders as aesthetic lifestyle choices rather than the serious medical conditions they are.

While pro-anorexia (“pro-ana”) and pro-bulimia (“pro-mia”) communities may provide a safe space to vent and emotional support to individuals who often feel stigmatized and misunderstood, they also create a venue to share tips on losing weight and concealing weight loss from others, as well as “thinspiration” images of very thin bodies to motivate weight loss. Community members may compete with each other in weight loss, ask the group to hold them accountable to their weight loss goals, or find “buddies” to go through the same difficult periods of food restriction.

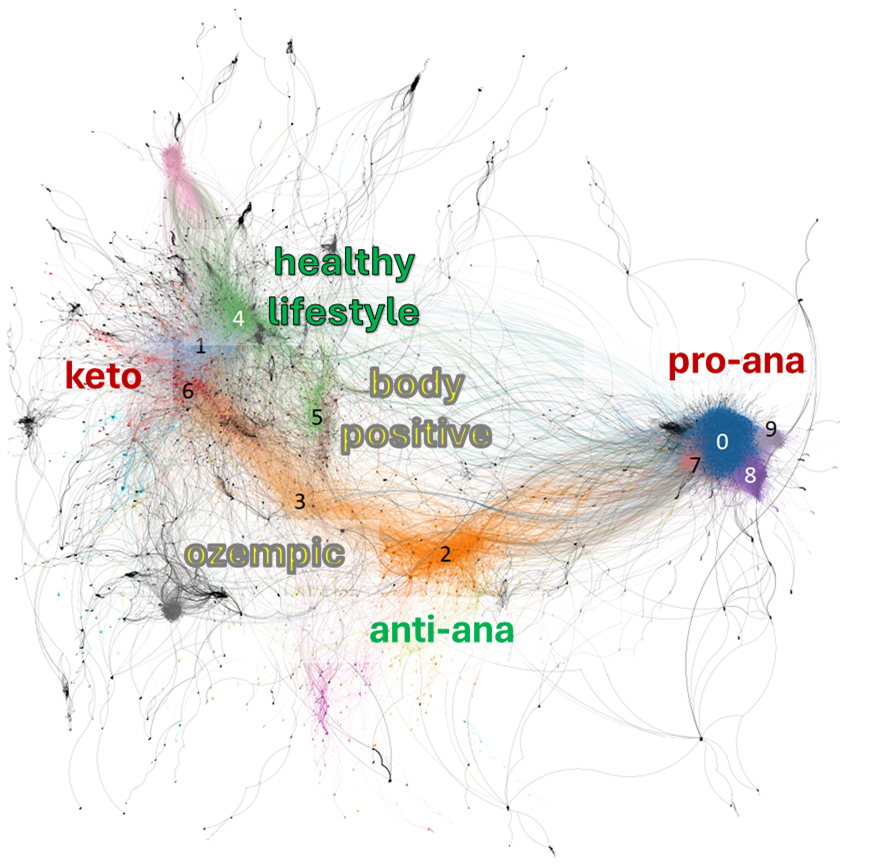

Figure 2: Retweet network in Twitter discussions about dieting, body positivity and eating disorders (adapted from Lerman et al., 2024). Nodes are users and edges link users who retweet one another. Users in communities 0, 7, 8, 9 frequently retweet one another, forming a dense echo chamber with relatively few external links. Topic analysis shows that these users glorify anorexia. Source: Lerman et al. (pre-print)

Vulnerable users who engage with pro-ana and pro-mia content may find themselves trapped in echo chambers where disordered cognitions and behaviors are normalized and reinforced, as can be seen in Figure 2. Nodes (dots) represent users and edges (lines connecting the dots) link users who retweet each other. Users are colored by the community they belong to, automatically identified using “community detection method.”¹ Users in communities 0, 7, 8, 9 frequently retweet one another, forming a dense echo chamber with few external links. The bulk of these users self-identify as part of the pro-anorexia community and they glorify anorexia in their posts. This dynamic mirrors online radicalization in other contexts: just as extremist groups groom individuals by isolating them from countervailing perspectives, pro-ED communities use shared language, insider knowledge, and emotional reinforcement to deepen commitment to harmful behaviors and delay recovery.

Without robust content moderation policies and algorithmic safeguards, these platforms continue enabling the creation and perpetuation of harmful content, reinforcing toxic social dynamics that harm vulnerable users. Effective moderation is therefore critical for disrupting these dangerous feedback.

Content Moderation Safeguards Vulnerable Users

Research shows that psychological distress can spread through media exposure in conditions such as tics, psychogenic illness, and even suicidality. Effective content moderation, including adherence to suicide reporting guidelines, has been proven to reduce harm from suicide reporting. Similar content moderation initiatives could reduce harmful content on social media while preserving supportive community dynamics.

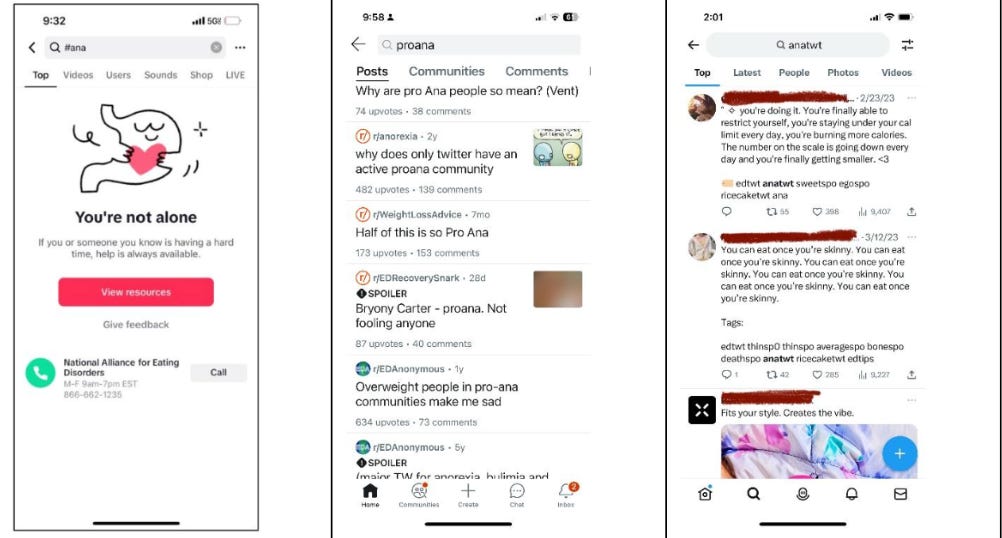

Figure 3: Screencaps of searches for anorexia-related content. (Left) Search for “ana” was blocked on TikTok, redirecting users to mental health resources. (Center) Search for “proana” on Reddit directs users to discussions in different forums. (Right) Searching for “anatwt” a term used by the pro-anorexia community on Twitter, returned posts promoting food restriction.

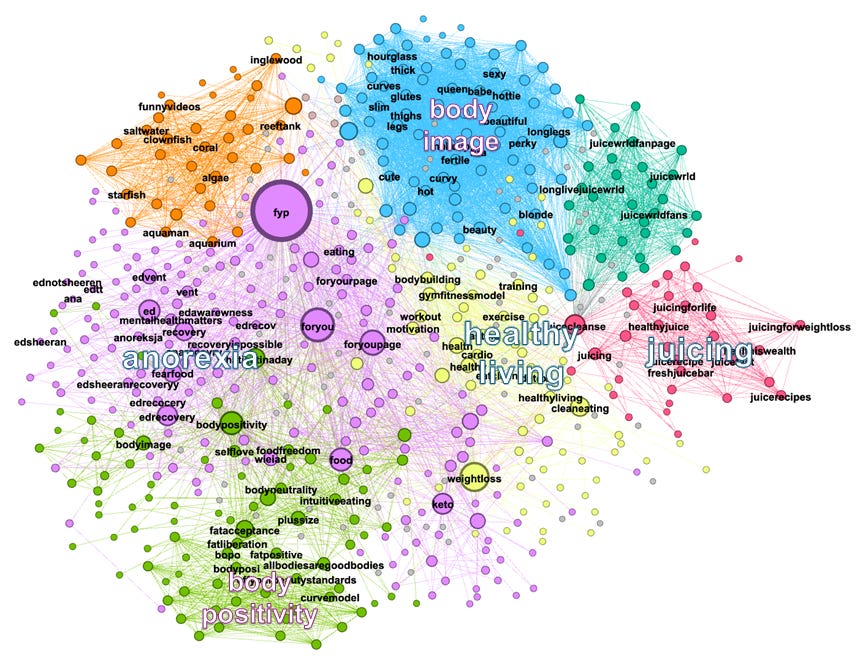

However, in the absence of regulation, content moderation is left up to the discretion of social media platforms and varies widely, creating starkly different information environments (Fig 3). The more strongly moderated platforms like TikTok and Instagram redirect searches for pro-anorexia content to mental health resources, although critics note these systems often fail to detect harmful information that is deliberately obfuscated. Reddit has taken more decisive action, banning pro-anorexia forums altogether. Volunteer community moderators on Reddit enforce guidelines in the remaining forums dedicated to eating disorders discussions. In contrast, Twitter’s historically lenient approach has allowed harmful content glorifying eating disorders and self-harm to proliferate. These moderation disparities fundamentally reshape information ecosystems. In one study, we compared TikTok and Twitter, using identical search terms related to dieting, fitness, body image, and eating disorders to collect online content. Our analysis revealed striking differences in content organization and reach. By linking popular hashtags that appeared in the same post, we created a hashtag co-occurrence network for each platform (Figure 4). These networks revealed similar topic clusters across both platforms, including “healthy living” (Twitter: #healthylife, #vegetarian, #cleaneating; TikTok: #eatclean, #healthyliving, #detox), “body positivity” (Twitter: #bodyconfidence, #curvygirl; TikTok: #curvemodel, #fatacceptance), and diet communities.

However, the platforms differed radically in eating disorder content. Though hashtags like #ana and #anoreksja appeared on both platforms, TikTok featured recovery-focused content (#recoveryispossible, #edrecovery) tightly integrated with body positivity content and mainstream discovery like #foryoupage. Even misspelled variations seemingly designed to evade moderation (#anarecovry, #edawarewness) predominantly linked to recovery-oriented content.

Figure 4: Hashtag co-occurrence network on (top) Twitter and (bottom) TikTok. Nodes are popular hashtags and edges link hashtags that are frequently used together. Node colors represent discovered communities and 15% of the labels are shown. Source: Lerman et al. (pre-print)

Twitter’s lax moderation, by contrast, allowed explicit pro-anorexia content—#thinspo glorifying extreme thinness, #bonespo and #deathspo showcasing even more extreme thinness, #proana and #promia promoting anorexia and bulimia as lifestyles. These hashtags formed a dense cluster of harmful content, even linking to self-harm and suicide-glorifying discussions (#shtwt, #goretwt), creating perilous rabbit holes that could trap vulnerable users in cycles of disordered thinking and behavior.

Conclusion

Although social media’s role in the youth mental health crisis remains a contested topic, its contributions to eating disorders are widely recognized. Conditions like anorexia and bulimia existed long before social media; however, today’s algorithm-driven social media platforms exacerbate body dissatisfaction—a well-established risk factor for these disorders—by continuously exposing users to idealized body standards. Beyond shaping perceptions, social media reinforces harmful cognitions and behaviors through peer influence, social normalization, and community feedback. These dynamics likely extend beyond eating disorders, contributing to the broader rise of social media-amplified psychological distress.

Girls, who spend more time on social media, are particularly vulnerable to its harms, which may help explain the widening gender gap in eating disorders and the broader gender asymmetry in the youth mental health crisis. For some, like Grace, the consequences are severe enough to require intervention. But her story is just one of many—one that underscores the urgent need for platforms to take responsibility and ensure that the next wave of young users isn’t met with the same harmful cycles that have already derailed so many lives.

Balancing the protection of minors and vulnerable users with the free speech rights of adults remains a challenge in moderating social media platforms. Although free expression deserves protection, the unchecked spread of harmful content—such as that promoting eating disorders—poses serious risks to young and vulnerable users. If platforms want to allow pro-anorexia content under the guise of free speech, then they must also take responsibility to ensure that minors are not exposed to it. This would require at a minimum that they enforce the existing age minimum of 13. Raising the age for opening social media accounts to 16, as Australia has done, would provide even more protection for the most vulnerable teens. The companies could also implement content restrictions, or even create separate spaces where such discussions are not accessible to younger users.

But the companies must do something. Their products are making children––and especially girls—sick.

Comments are closed.