THE HAMAS REGIME IN GAZA: C. JACOB*…FROM MEMRI

http://www.memri.org/report/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/5484.htm

PLEASE CONSIDER A CONTRIBUTION TO THIS GREAT ORGANIZATION….

https://secure3.convio.net/memri/site/Donation2?df_id=1800&1800.donation=form1

Preface

Four years after its takeover of Gaza, in June 2007, Hamas has successfully established an independent entity there, separate from the West Bank. Since the takeover, Hamas has managed to strengthen itself economically (though its resources have been directed more towards reinforcing the movement than towards promoting the wellbeing of the population). It has also managed to consolidate its military strength, and has continued to prepare itself for the next confrontation with Israel. For the time being, however, the movement has found it beneficial to maintain a tahdiah (lull) with Israel, though occasionally the tahdiah is disrupted, not only by other organizations in Gaza but also by Hamas itself.

The Hamas regime in Gaza is a dictatorial one, characterized by numerous violations of human rights. Its policies and draconian rule have caused a drop in its popularity among the public (a fact of which the movement’s leaders are aware), but not to the point of threatening its rule.

The movement’s relations with other forces in Gaza – especially with the Salafi jihadists, the Islamic Jihad movement, Fatah and the Popular Front – are strained, and internal conflicts within the movement have surfaced as well. In April-May 2011, Hamas and Fatah signed a reconciliation agreement, but there are numerous doubts regarding its chances of success.

Over the next week MEMRI will be releasing this report in seven chapters, including chapter one today.

Chapter 1– Fatah-Hamas Relations

Chapter 2 – Hamas’s Military Conduct vis-à-vis Israel

Chapter 3 – Hamas’s Administration of Gaza

Chapter 4 – Internal Conflicts within Hamas

Chapter 5 – Islamization of Gaza

Chapter 6 – Hamas’s relations with Islamic Jihad, Salafi-Jihadis

Chapter 7 – Hamas’s Relations with Egypt

Chapter 1: Fatah-Hamas Relations

Introduction

The Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007 caused a deep rift within Palestinian society, and gave rise to intense hostility between Hamas and Fatah/the Palestinian Authority. Fatah accused Hamas of murdering its activists and of aiming to take over the West Bank in addition to Gaza, whereas Hamas accused Fatah of treason and challenged the PA’s legitimacy.

In April-May 2011, four years after the Hamas coup in Gaza, the two movements signed a reconciliation agreement accompanied by a document of understandings. However, today, one month after the reconciliation ceremony, the details of the agreement remain uncertain. The only document whose content is known and uncontroversial is the document of understandings, an initialed copy of which was published in the Arab and Palestinian press. As for the document to which these understandings relate – namely the agreement itself – its precise content remains unclear, and there seems to be tacit agreement not to officially release it. Against this backdrop, various versions of the agreement and its details have been published, and there may have even been deliberate attempts at deception.

Below is a review of Hamas’s relations with Fatah, from the June 2007 Gaza coup to the April-May 2011 signing of the reconciliation agreement.

I. Deepening Hostility in the Wake of the Gaza Takeover

Following the coup, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud ‘Abbas fired the Hamas ministers in the national unity government. Hamas, however, refused to recognize these dismissals, and likewise refused to recognize the legitimacy of PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s government or of ‘Abbas’s presidency. Instead, it saw Isma’il Haniya and his government as the legitimate representatives of the Palestinian people. In practice, two separate entities existed, neither of which recognized the other, in a situation defined by mutual delegitimization.

Hamas referred to the Palestinian Authority as “the Ramallah Authority” or “the Dayton Authority” (after U.S. General Keith Dayton, who trained the Palestinian Authority security forces), and to its president as “president of the defunct [Palestinian] Authority.”[1] Fatah, for its part, referred to Hamas’s takeover of Gaza as the “coup,” “schism,” or “split,” while Hamas referred to it as its “settling” (of the conflict with Fatah). In Fatah circles, activists murdered by Hamas, such as Muhammad Al-Sawirki, who was thrown from a multistory building, and Samih Al-Madhoun, who was lynched and his body mutilated, have become martyrs and symbols of the struggle between the two movements.

Statements by Fatah officials reflected the hostility between the movements. In the wake of the May 2010 Freedom Flotilla events, the following statement appeared on a Fatah-affiliated website: “In 2007, Hamas carried out the most atrocious massacres of Palestinians, killing 550 people, including children and the elderly. Such being the case, why shouldn’t Israel carry out massacres in a world that supports those who spill the blood of their own people [i.e. Hamas]?”[2] Fatah Central Committee member Muhammad Dahlan said: “Hamas has achieved nothing in Gaza, and boasts of the [Gaza] Strip’s destruction. Hamas wanted to combine governing [Gaza] with resistance [against Israel], but has become a government of tunnels and smuggling.”[3] ‘Adel ‘Abd Al-Rahman, columnist for the PA daily Al-Hayat Al-Jadida, wrote: “The Palestinian knows that the resistance leaders in the Gaza Strip are no less dangerous than the occupation.”[4]

Cartoon on Hamas-affiliated website following the movement’s takeover of ‘Abbas’s home in Gaza:

“Hello?… Wrong number. Mahmoud ‘Abbas has run away from home. This is the ‘Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades [the military wing of Hamas] speaking.”

Source: Paldf.net

II. Reciprocal Accusations

PA Accusations Against Hamas

Hamas Leaders Fled During the Gaza War

Following the last war in Gaza, in December 2008/January 2009, Mahmoud ‘Abbas accused the Hamas leadership of “fleeing to Egypt in ambulances during the war and leaving the people [of Gaza] to die.” ‘Abbas also held Hamas responsible for the suffering of the Gazans during the war, because it had refused to renew the tahdiah [lull] and continued firing rockets at Israel, leading to the Israeli invasion of Gaza.[5] Mahmoud Al-Zahhar, in response, said that Hamas would sue ‘Abbas for his statements.[6]

Hamas Murders and Tortures Fatah Members, and Incites to Violence

The PA has also accused Hamas of inciting against it and of murdering and torturing Fatah members. In January 2009, PA Religious Affairs Minister Mahmoud Al-Habbash, then serving as minister of social affairs, said that during the Gaza war alone, Hamas had killed 19 civilians in cold blood and shot 61 others in the legs.[7] Reports indicate that the campaign against Fatah continued after the war as well. In April 2010, a Preventive Security officer in Jabalya, ‘Abd Al-Nasser Hamid, was shot in the legs by Hamas gunmen.[8]

Following an attempted assault on ‘Abd Al-Hamid Al-‘Eila, a Palestinian Legislative Council member from Fatah, a Fatah-affiliated website stated that “the deed resulted from an atmosphere of incitement that has lately been [generated] in Gaza by some of [Hamas’s] mouthpieces against Fatah members, MPs and operatives.”[9] Fatah MPs in the Legislative Council accused Hamas of being behind the attack on Al-‘Eila, adding: “It reflects the extent of the black hatred that these militias and the people behind them harbor for the other Palestinian [side], and exposes as false Hamas’s claims that it desires peace [with Fatah].”[10]

PA and Fatah sources claimed that, aside from inciting murder, Hamas also employed brutal methods of torture. The PA news agency WAFA reported that “Hamas’s militias have invented gruesome methods for torturing and interrogating the Fatah personnel it has abducted. The coup government of Gaza outdoes the interrogators and agents of the Israeli Mossad in one domain only: in the invention of torture and interrogation methods [for use] against Fatah members and members of the [PA] apparatuses, which are more severe and brutal than [those used] on [Palestinian] prisoners in Israeli prisons.”[11]

Human rights organizations enumerated 16 methods of torture that the Hamas security apparatuses use on prisoners, including putting out cigarettes on their skin. These organizations stated that Fatah likewise employs torture against prisoners in the West Bank.[12]

The PA and Fatah accused Hamas of using religious and public facilities as venues for incitement to violence, torture, and murder. PLO Executive Committee Secretary-General Yasser ‘Abd Rabbo claimed that Hamas had “turned the guns it had once aimed at Israel against Fatah… and transformed the mosques, schools, and hospitals into holding cells and interrogation facilities where they torture Fatah members and other national leaders.”[13] PA official and Al-Ayyam columnist Hani Al-Masri wrote: “The extremist element in Hamas, which excludes the other and accuses him of apostasy and treason, does not believe in truth, patriotism, democracy, or realism. This element has appointed itself the guardian of religion, the homeland, the people, and the land, on the pretext that it is Allah’s shadow on earth and has been sent on a divine mission which cannot be questioned… [It operates under the assumption] of one fact: Whoever is not with me is against me, and whoever is against me is an apostate who has left the fold of Islam and deserves to be exterminated. This element saw the Gaza coup as the second liberation [of Gaza, after the Israeli withdrawal,] and as a victory over secularism… Hamas has turned the mosques into its party offices, which serve it against its enemies.”[14]

The Fatah-affiliated website Alaahd.com reported, citing Gaza residents, that Hamas had used mosque loudspeakers to call for the murder of Fatah members, and broadcast cries such as: “O knights of the Al-Aqsa Brigades, draw your weapons and attack ‘Abbas’s people, and strike at them without mercy.”[15]

Hamas Is Planning To Take Over West Bank

A further claim against Hamas was that it intended to take over the West Bank as well as Gaza. Senior Hamas leaders in Gaza announced their intention to do this. During a Hamas march in the Jabalya refugee camp, Hamas official Nazzar Riyan (who was killed in the 2008/2009 Gaza War) said: “Next autumn, we will pray at the Muqata’a; ‘Abbas will fall like the leaves in autumn.”[16] PA President Mahmoud ‘Abbas said that the PA had information that Hamas planned to carry out violent operations in the West Bank,[17] and added that his security apparatuses would strike anyone who harmed the Palestinian interest.[18]

Palestinian security apparatuses spokesman ‘Adnan Al-Damiri revealed that “the PA security apparatuses seized $8.5 million from Hamas members in the West Bank intended for funding the establishment of a Hamas security apparatus [there].” He added that in the first half of 2009, the PA had also seized large quantities of weapons and explosives in Nablus, Hebron, and Qalqiliya, and uncovered apartments that Hamas had purchased for use as operations rooms, for overseeing the abduction of West Bank PA officials, and for otherwise violating PA law and undermining security.[19]

In October 2010, Palestinian sources said that the PA security apparatuses had found a sizeable Hamas ammunition dump in Ramallah that included RPGs.[20] One month later, sources in Nablus reported that a Hamas squad operating in the northern West Bank had planned to assassinate Nablus provincial governor Jibril Al-Bakri. Fatah spokesman Ahmad ‘Assaf accused Hamas of attempting to undermine stability in the PA territories and of fomenting civil war.[21]

Hamas Serves Iran’s Interests

Fatah accused Hamas of promoting Iran’s agenda. Fatah spokesman Faez Abu ‘Ayta said that Hamas political bureau head Khaled Mash’al was “serving up the Arab nation and its national interests as fodder to the Iranian enterprise, in exchange for narrow sectarian interests and a fistful of dollars.” He added that Iran was interfering in Arab affairs and sparking wars that were draining the Arab nation.[22] PLO Executive Committee Secretary Yasser ‘Abd Rabbo accused Hamas of aspiring to set in place a “dark emirate” supported by Iran, and of working “to actualize a regional scheme to turn Gaza into an entity that is separate and cut off from the West Bank.”[23]

Samih Shabib, columnist for the PA daily Al-Ayyam, wrote that Hamas was counting on Iran’s support: “[Hamas] is gambling that there will be changes that will result in an increase in Iran’s influence in the Middle East – and then [Hamas’s] enterprise in Gaza will be part of an entire regional enterprise.”[24]

Hamas Accusations Against PA

The PA Backstabbed Hamas

Hamas, for its part, stated that the PA’s relinquishment of the resistance constituted collaboration with Israel, and an act of “high treason against the Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims.”[25] Palestinian Legislative Council member from Hamas Salah Al-Bardawil stated that Mahmoud ‘Abbas had collaborated with Israel in the Gaza war and was “involved in the assassination of senior Hamas official Sa’id Siyam.”[26] Senior Hamas official Isma’il Radwan said: “President ‘Abbas sits down [and negotiates] with Israel while refusing to reconcile with Hamas.”[27]

In June 2009, Hamas reacted angrily to the killing of members of its military wing, the ‘Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades, by the PA in Qalqiliya. Mushir Al-Masri, secretary of the Hamas faction in the Palestinian Legislative Council, said: “The hand of justice will catch up with the PA president whose term in office is over, Mahmoud ‘Abbas, and with the criminal Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. They will not escape the ‘Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades… Hamas and its men in the West Bank will in the future treat the PA security apparatuses like the occupation, and will resist them in every possible way.”[28]

Following comments by PLO representative in the U.N., Riyadh Mansour, who described the resistance as “harming Israel,” Hamas demanded that he be prosecuted. Hamas government spokesman Taher Al-Nounou accused the PA of exploiting international platforms to incite against Hamas while clearing Israel of war crimes accusations.[29]

The PA Is Illegitimate

As part of its efforts to firmly establish its control, Hamas has attempted to delegitimize the PA and the PLO. The leaders of Hamas do not recognize Mahmoud ‘Abbas as the Palestinian president, on the grounds that his term in office ended in January 2009 (four years after his election in 2005), and therefore claim that the PA, headed by ‘Abbas, is illegitimate. In a January 28, 2009 “victory” rally in Qatar, Khaled Mash’al said that the Palestinian factions were planning a “surprise” move of “establishing a new supreme national council, which will represent the Palestinians within [Palestine] and outside it, and will include all the national Palestinian forces and all the sectors of the Palestinian people… [because] the PLO, in its current state, no longer constitutes a supreme authority for the Palestinians.”[30] He added that the Palestinian resistance was aspiring to establish a leadership that would be a source of authority for the Palestinians until the implementation of the 2005 Cairo Agreement, which mandated reforms in the PLO.[31]

At another victory rally in Damascus, Khaled Mash’al said, “No Palestinian body opposed to the path of resistance chosen by the Palestinian people is legitimate.”[32]

Hamas official Ahmad Baher, deputy speaker of the Palestinian Legislative Council, called for prosecuting ‘Abbas, accusing him of posing as the PA president and of planning election forgery.[33]

Hamas also sought to neutralize the PA role in aid to Gaza. Hamas official Mushir Al-Masri said that Hamas “does not rule out bringing aid into the Gaza Strip, providing that it is in trustworthy hands, and that it does not fall into corrupt hands [i.e. those of Fatah]… The PA is insisting that it alone bring in the aid, so that [the aid] can be used as a card to pressure Hamas [to back down on the issue of] the Palestinian reconciliation.”[34]

When the Goldstone Report was published, Hamas used the report’s recommendations to undermine the PA’s status. Hamas attempted to upgrade its own status in the international arena by submitting a response to the U.N. on behalf of the PA. The response document was submitted on behalf of the PA Justice Ministry, on the PA letterhead and with the signature of the Hamas justice minister, Muhammad Faraj Al-Ghoul. Hamas expected that the report’s acceptance by the Gaza branch of the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights would constitute recognition of Hamas’s status as representative of the PA in Gaza. Indeed, Muhammad Faraj Al-Ghoul clarified that the document, which was published in the Hamas organ Al-Risala, did not express Hamas’s response to the Goldstone Report, but the response of the entire Palestinian government.[35]

The PA Is Making Political Concessions to Israel

Hamas accused the PA of making concessions to Israel. Hamas called for PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad to be prosecuted after he said, in an interview with the Israeli daily Haaretz, that he would be willing for the refugees to return to a Palestinian state rather than to their homes in Israel.[36]

In early 2011, after Al-Jazeera leaked PA documents regarding the negotiations with Israel, Hamas accused the PA of making far-reaching political concessions.

III. The Reconciliation Efforts

The reconciliation agreement signed in April-May 2011 was unexpected, following as it did years of attempts to end the Hamas-Fatah schism. It was preceded by numerous unsuccessful efforts:

Fatah-Hamas Understandings Remain Unimplemented

In October 2009, Hamas thwarted Egyptian efforts to reach an intra-Palestinian reconciliation agreement by demanding that amendments be made to the reconciliation document, which Fatah had already signed. Fatah and Egypt rejected Hamas’s demands, but said they would be willing to discuss Hamas’s reservations and remarks after it signed the document. During his tour of Arab states, Mahmoud ‘Abbas asked their leaders to convince Khaled Mash’al to sign the document and to meet with him thereafter.

Egypt reacted to Hamas’s refusal to sign the reconciliation document with harsh criticism, and even canceled a visit of a Hamas delegation to Egypt. It accused the movement of evading reconciliation, and rebuked its leaders, saying that they should “regard Egypt in accordance with its weight and importance, and not as a [mere] organization, movement, or faction [whose wishes can be ignored].”[37]

As part of the efforts to advance a reconciliation agreement, Nabil Sha’th arrived in Gaza for a meeting with Isma’il Haniya in which several understandings were reached, e.g. “to end all mutual media attacks [between Fatah and Hamas] and replace them with a campaign for unity; to end all political persecution in the West Bank and Gaza; and to allow Fatah members who fled Gaza for the West Bank after Hamas’s takeover to return.”[38] In practice, these understandings were not implemented.

In further meetings between Fatah and Hamas, in Syria and Qatar, Hamas reiterated its demand to amend the reconciliation document.[39] Nabil Sha’th stated in response: “The side that refuses to sign the reconciliation document [i.e. Hamas] is not ready for reconciliation.”[40]

Accusations Against U.S., Iran; Expressions of Pessimism on Both Sides

Hamas, for its part, accused the U.S. of sabotaging the reconciliation process. When, in June 2010, a reconciliation committee headed by Palestinian businessman Munib Al-Masri failed to produce results, Hamas political bureau deputy head Moussa Abu Marzouq claimed that “America [had] vetoed the reconciliation efforts.”[41]

The PA, for its part, blamed Iran for the failure of the reconciliation efforts. ‘Abbas remarked that, unlike Syria, which had not interfered in the reconciliation process, Iran’s negative interference had prevented reconciliation. He added that this country interfered in matters everywhere, including in the Persian Gulf, Yemen, Lebanon and Palestine.[42]

Following the failure of the June 2010 reconciliation effort, both sides expressed profound pessimism. Ashraf Jum’a, a member of the Fatah faction in the Palestinian Legislative Council, said: “I do not believe that we will succeed [in achieving reconciliation] – and, even worse, we seem to be destined to fail. [Today,] a year after the dialogue began… we are back where we started, with accusations of apostasy, mudslinging, and rejection of the other…” He called on the Palestinian people to launch a popular uprising against the current schism, warning that if they did not, “there would be no reconciliation, not even decades from now.”[43]

Hani Al-Masri, a member of the reconciliation committee and columnist for the PA daily Al-Ayyam, wrote: “Hamas did not sign the Egyptian [reconciliation] document because it is fettered by slogans and fears that prevent it from finalizing the reconciliation. It places its narrow interest above the general interest. Had Hamas wanted to finalize the reconciliation, it would have signed the Egyptian document despite its reservations…”[44]

In contrast, Hamas government secretary Dr. Muhammad ‘Awwad said: “The problem lies not in signing [the reconciliation document] but [in what happens] afterwards. We do not want to repeat [our] previous experience of signing for the sake of signing, and then ending up back where we started.”[45] When it was first reported in mid-2010 that ‘Abbas might visit Gaza, Hamas official Mahmoud Al-Zahhar said: “Abu Mazen should not come to Gaza before actual steps are taken regarding the Palestinian prisoners [i.e. Hamas prisoners] in the West Bank and before reconciliation is achieved, because there is fear that families who lost their sons in the [Gaza] war and believe that he collaborated with Israel during this war, [may seek revenge].”[46]

In September 2010, reconciliation talks were renewed following a meeting between Khaled Mash’al and then Egyptian intelligence chief ‘Omar Suleiman, in which the latter expressed that Egypt still wanted a reconciliation agreement and would also act to ensure its implementation. Two rounds of talks were held at the time. The first, on September 24, 2010 in Damascus, was marked by a positive atmosphere. ‘Azzam Al-Ahmad, head of the Fatah faction in the Palestinian Legislative Council, said that an understanding had been reached on the issues of the PLO and the elections, but that one issue still remained unresolved – namely, that of security.[47]

A detailed list of the understandings that had been reached was presented at a conference of the Palestinian factions in Damascus, chaired by Khaled Mash’al: an election committee and election tribunal would be established on agreed-upon terms and an election date set; the PLO would be reorganized and its hierarchy re-determined. Fatah agreed to all of these clauses, but requested more time to consult over the issue of the proposed supreme security council. Mash’al reported: “We told [the Fatah representatives] that we are opposed to negotiations [with Israel], and they responded: We, too, have despaired of them.”[48]

A second session was not held until November 9, 2010, due to Fatah’s refusal to meet in Syria, following an argument between Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and PA President Mahmoud ‘Abbas at a meeting of the Arab League’s Follow-Up Committee in Libya in early October 2010. Ultimately, Fatah was appeased and agreed to meet in Damascus, but, unlike the first session, the second failed to yield results, to the extent that Fatah representative ‘Azzam Al-Ahmad described it as a waste of time.[49] Others in Fatah claimed that Hamas had come to the session unprepared or determined not to reach an arrangement. Hamas on its part accused Fatah of reneging on commitments it had made at the first session of talks.[50]

The bone of contention was and remains the issue of security. Hamas demanded that a supreme security council be established on agreed-upon terms, even though the reconciliation document specified that it would be established by presidential decree. It has likewise demanded the reorganization of the security apparatuses both in Gaza and in the West Bank. Fatah has rejected this demand, on the grounds that the security forces in the West Bank have already been reorganized based on professional parameters, whereas in Gaza Hamas’s security apparatuses have not been reorganized since the 2007 coup.[51]

Even after the Damascus meetings, neither Fatah nor Hamas had high hopes for the reconciliation talks. The prevailing view was that it would be very difficult to bridge the gaps on the security issues, and that, even if an agreement was signed, it would be worthless, because as things stood, there was little chance of its successful implementation.

Former PA minister Ziad Abu Ziad wondered how long the futile efforts would continue: “The ongoing dialogue between Fatah and Hamas [aimed at] restoring the situation in Gaza to what it was [before] the schism is like [the efforts of] a thirsty man chasing a mirage. A true dialogue will be one that includes all the Palestinian elements and factions, and is aimed at finding a new legal formula for the relations between the West Bank and Gaza – because Hamas is not going to surrender to Fatah in Gaza, just like Fatah is not going to yield to Hamas in the West Bank.”[52]

Dr. Ibrahim Hamami, who writes on a Hamas-affiliated website, was likewise skeptical about the possibility of reaching an understanding: “Any sensible person understands that there can be no national unity [if this means that] Hamas [must be] part of security apparatuses that coordinate with the occupation, work in its service, and scheme with it.”[53]

Reconciliation Efforts Renewed Following Changes in Arab World

In the wake of the revolutions that swept the Arab world in early 2011, the issue of reconciliation was again raised. Using Facebook, Palestinian youth organized demonstrations on March 15, 2011, in both the West Bank and Gaza, against the Palestinian schism.

Demonstration in Bethlehem against Palestinian schism (Source: maannews.net, March 15, 2011)

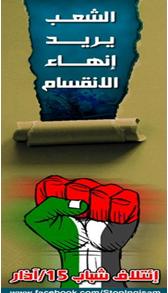

The slogan of the March 15, 2011 demonstrations – “The People Want an End to Schism” – with the logo of the “Coalition of the March 15 Youth” (Source: facebook.com/StopInqisam)

PA leaders likewise took up initiatives aimed at ending the Palestinian schism. Hamas Prime Minister Isma’il Haniya called on ‘Abbas and Fatah to immediately renew the national dialogue in order to meet the demands of the Palestinian people. In response, ‘Abbas announced on March 16, 2011 that he was prepared to come to Gaza in order to establish a government of independents aimed at organizing elections for the presidency, the Legislative Council, and the PNC within six months. ‘Abbas charged Haniya with organizing the visit.[54] Several days later, representatives from Fatah and Hamas met in Nablus; those from Hamas called for the release of the political prisoners from both movements in order to create a positive atmosphere for reconciliation.[55]

An important contribution to the reconciliation efforts was made by PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, who defused the security issue by backing down from the PA’s previous stance and allowing Hamas to retain its security apparatuses as they are. As part of his reconciliation initiative, Fayyad called to establish a national unity government whose first task would be to adopt a security policy of avoiding armed resistance while promoting the Palestinian rights. He pointed out that this was the official policy of the PA in the West Bank, and that, in practice, Hamas was also implementing it in Gaza. This national unity government would oversee the implementation of this security policy by means of the institutions extant in Gaza and the West Bank, without changing them.[56]

IV. The 2011 Reconciliation Agreement

In April-May 2011, Fatah and Hamas signed a reconciliation agreement and a document of understandings. Apparently, one of the factors which prompted this breakthrough was the erosion in Hamas’s status in Gaza, and the movement’s fear of further deterioration in its status as a result of the uprisings in the Arab world. Another contributing factor was the initiative by ‘Abbas and Fayyad to end the schism before September 2011, at which time the Palestinians plan to seek a U.N. recognition for a Palestinian state in the 1967 borders (as part of this initiative, ‘Abbas expressed a willingness to visit Gaza and Fayyad proposed that Hamas would be allowed to maintain its security apparatuses as they are). Still other factors were the advent of the new regime in Egypt, which renewed the efforts to bring about a reconciliation between the two movements; pressure by the Palestinian public, which demanded an end to the schism; as well as Hamas’s apprehensions regarding its future in Syria in light of the anti-regime protests there.

In late April 2011, the two sides signed a document of understandings in Cairo, which included mainly technical points. The document of understandings specifies that a national unity government will be established, that elections will be held for the presidency, the PLC and the PNC, and that an interim leading body will be established until elections are held.

The two movements left many issues unresolved, deferring them for discussion in committees to be established, such as the Supreme Security Committee, which is to discuss the reorganization of the Palestinian security apparatuses. Officials from both Fatah and Hamas, as well as Palestinian columnists, expressed a concern that the road to true reconciliation would be beset with obstacles.

On the face of it, Hamas made a concession in signing the agreement after a long period of refusing to do so. However, Hamas stands to gain from this move, since the way is now clear for it to enter the PLO and perhaps even take it over. (That is, if the agreement is actually implemented, which is doubtful). In addition, Hamas may work to increase its influence in the West Bank and to take over the PA by winning the presidential elections.

Comments are closed.