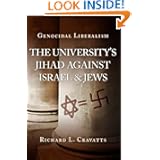

EDWARD ALEXANDER: REVIEWS “GENOCIDAL LIBERALISM- THE UNIVERSITY’S JIHAD AGAINST ISRAEL AND JEWS” BY RICHARD CRAVATTS

http://spme.net/articles/8647/3/11/Genocidal-Liberalism-The-Universitys-Jihad-Against-Israel-Jews.html

“…….In subtler ways, the debasement of academic liberalism itself rendered its practitioners incapable of recognizing that Israel’s foundation was one of the greatest affirmations a martyred people had ever made. Liberalism grew more and more dogmatic and dictatorial, inclined to transform certain academic disciplines into “grievance” studies, receptive to the (fascist) idea that physiology determines culture, unashamed to select political desperadoes like MIT’s Louis Kampf to run their professional organizations. More and more they singled out Israel as the globe’s most blatant “anachronism” in a world that was (supposedly) moving happily away from the very idea of the nation-state and national religious identity. Apologetics for what Michael Lerner had called the “earned antisemitism” of black violence against Jews in America now became the trademark of advanced liberals when estimating Palestinian violence against Israelis.”

By locating a genocidal impulse at work in today’s universities, the explosive title of this book (somewhat weakened by that unfortunate word “jihad”) inevitably calls to mind an earlier book called Hitler’s Professors: The Part of Scholarship in Germany’s Crimes Against the Jewish People (YIVO, 1946), by Max Weinreich. That classic text cast a backward look at the multitude of German professors (almost none of them “liberal”) who served their dictatorial master’s needs by making antisemitism academically respectable and openly complicit in the destruction of European Jewry. Their task was to put scholarship at the service of “the Jewish question.” But now, so Professor Cravatts argues, the Jewish question has been renamed “the Israeli question” and the “scholars” who zealously pursue it are mainly liberals. Whereas Hitler’s professors kept asking “Do Jews have the right to live?” their liberal descendants keep asking: “Does Israel have the right to exist?” The latter, like the former, answer NO.

How, asks Cravatts, “did the academic left come to hate Israel,” which had been looked on by most (not all) liberals prior to June 1967 with approval and sympathy? By 2007 Stanley Fish could observe in the New York Times that at most American universities “anti-Israel sentiment flourishes and is regarded more or less as a default position.” Moreover, added Fish, “When hostility to Israel comes, antisemitism is not far behind.”

In spring 2002, I arranged, through faculty channels but with great difficulty, for Daniel Pipes to give a lecture at my university. Even before a public announcement was made, I received a barrage of stern warnings by e-mail—from American Muslims of Puget Sound, from “progressive” student groups, from a wide assortment of Israel-haters– against proceeding. When I refused to cancel the lecture, these complainers demanded equal time to “rebut” the speaker, which (of course) I also refused. For nearly a month I had to meet weekly with campus police to turn over threatening e-mails and to discuss security arrangements for Mr. Pipes. On the evening of the lecture I had to deliver Pipes, via an underground tunnel, to two burly armed policemen who escorted him up into the lecture hall. And the University of Washington community is far less hostile to Israel than its counterparts at such institutions as University of California (Berkeley, UCLA, or Irvine, for example) or University of Pennsylvania—or Brandeis. (“That’s because you have fewer Jewish students,” was how one wag explained the difference to me.)

Cravatts names a variety of causes for the sharp decline in Israel’s status in academe. Having been badly defeated on the field of battle in June 1967, the Arabs proved far more adept than their Jewish enemies in the war of ideas. For nineteen years, from 1948-67, the suddenly “occupied” territories had been entirely in the hands of the Arabs, theirs to do with whatever they pleased; yet it had never occurred to them to establish a Palestinian state there. Now, after endlessly reiterating that “Israel’s existence is itself an aggression” (Nasser’s words) and having failed to “throw the Jews into the sea,” they presented their cause to the world as that of a beleaguered people deprived of its own state. This strategy appealed powerfully to “progressives,” including (if not especially) the Jewish ones. By 1970, Irving Howe (a non-Zionist himself) lamented: “Jewish boys and girls, children of the generation that saw Auschwitz, hate democratic Israel and celebrate as ‘revolutionary’ the Egyptian dictatorship;…a few go so far as to collect money for Al Fatah, which pledges to take Tel Aviv. About this, I cannot say more; it is simply too painful.”

In subtler ways, the debasement of academic liberalism itself rendered its practitioners incapable of recognizing that Israel’s foundation was one of the greatest affirmations a martyred people had ever made. Liberalism grew more and more dogmatic and dictatorial, inclined to transform certain academic disciplines into “grievance” studies, receptive to the (fascist) idea that physiology determines culture, unashamed to select political desperadoes like MIT’s Louis Kampf to run their professional organizations. More and more they singled out Israel as the globe’s most blatant “anachronism” in a world that was (supposedly) moving happily away from the very idea of the nation-state and national religious identity. Apologetics for what Michael Lerner had called the “earned antisemitism” of black violence against Jews in America now became the trademark of advanced liberals when estimating Palestinian violence against Israelis.

Liberals more and more condemned Israel not in proportion to her alleged misdeeds against Palestinians but in lockstep with Palestinian terror against Israelis. Paul Berman, himself a liberal but a liberal chastened by experience, reflection, and renouncement, defined the process brilliantly: “Each new act of murder and suicide testified to how oppressive were the Israelis. Palestinian terror, in this view, was the measure of Israeli guilt. The more grotesque the terror, the deeper the guilt….And even Nazism struck many of Israel’s critics as much too pale an explanation for the horrific nature of Israeli action. For the pathos of suicide terror is limitless, and if Palestinian teenagers were blowing themselves up in acts of random murder, a rational explanation was going to require ever more extreme tropes, beyond even Nazism.” Liberal academicians like Gayatri Spivak (Columbia), Karen Armstrong (Leo Baeck College and PBS), Jacqueline Rose and Ted Honderich (London University) became the glib metaphysicians of this mad science, professors for suicide bombing.

Cravatts has undertaken a very ambitious survey of the ideological roots of anti-Israelism, of the major anti-Israel “battlegrounds” (California campuses, Middle East Studies programs, radical student groups, Orwellian hate-fests, Boycott/Divestment/Sanction campaigns, and kangaroo courts called “academic conferences” in which Israel is permanently on trial. His concluding chapter offers practical suggestions on how to throw back this relentless academic campaign to blacken Israel’s reputation in order expel it from the family of nations.

A map so large as Cravatts’ cannot possibly provide a detailed examination of each location it includes; but if I had to choose one that best epitomizes this landscape of outrage and also justifies Cravatts’ shocking title I would choose “the Paulin affair” of 2002-03.

George Orwell once posed the question of whether we have the right to expect common decency from minor poets. The prominence of Tom Paulin, whose poetry fluctuates between political doggerel and free verse of the sort that reminded Robert Frost of “playing tennis with the net down,” in Britain’s literary and academic world makes that question as compelling as ever it was. Until the year 2000 Paulin was also a critic aggressively politicizing literature, viewing the work of D. H. Lawrence, for example, through the prism of “post-colonialism,” a pseudo-scholarly enterprise whose primary aim is the delegitimization of Israel. But in October 2000 he persuaded himself that an Indian student for whom he served as “moral tutor” at Oxford’s Hertford College had been discriminated against by an Israeli professor of Islamic philosophy named Fritz Zimmermann. He alleged (in over 200 phone calls on behalf of his protégé) that Zimmermann had been “bunged off to Israel to get out of the way.” The case was dismissed in a Reading court on April 23, 2002 when the presiding judge severely rebuked Pauline, pointing out that Zimmermann “was not in any way motivated by race,” that “neither Mr. Ahmed [the student] nor Mr. Paulin honestly thought there was any racial element in the complaint.” He also pointed out that Paulin’s abstruse research into Zimmermann’s ethnic and national identity was flawed: he was neither Jewish nor Israeli, but a German Gentile.

Genocidal Liberalism: The University’s Jihad Against Israel & Jews by Richard L. Cravatts (Jan 20, 2012)

The court’s judgment was handed down just a few days after Paulin made his most ambitious bid for world fame by telling an interviewer for the Cairo weekly paper, Al Ahram, that he abhorred Brooklyn-born Jewish “settlers” and believed “they should be shot dead. I think they are Nazis, racists, I feel nothing but hatred for them.” (For good measure, he added that Israel had “no right to exist.”) This unambiguous incitement to raw murder was clearly in violation of British law. The Terrorism Act 2000, section 59, states: “A person commits an offence if he incites another person to commit an act of terrorism wholly or partly outside the United Kingdom. It is immaterial whether or not the person incited is in the United Kingdom at the time of the incitement.” But Paulin uttered his call for the murder of Jews living in the disputed territories with complete impunity—though not without substantial reward. He soon took to the welcoming pages of the London Review of Books (January 2003) with a 133-line poem called “On Being Dealt the Anti-Semitic Card.” Here, along with numerous apoplectic and incoherent utterances on the Crusades, Joseph de Maistre, the Enlightenment, and Christian fundamentalism, he spewed forth his extreme dissatisfaction with being called an antisemite: “the program though/of saying Israel’s critics/are tout court anti-Semitic/is designed daily by some schmuck/to make you shut the fuck up.”

But the publicity generated by the two British scandals was as nothing compared with what was provided Paulin in America, courtesy of Harvard and Columbia. In November 2002 Paulin, now a visiting professor in the English Department of Columbia, was invited to be the Morris Gray lecturer by the Harvard English department. Cravatts quotes that department’s chairman, Lawrence Buell, explaining the selection as Harvard’s way of affirming its “belief in the importance of free speech…in the academy.” Rumors were also circulating that Columbia was considering a permanent appointment for him there—perhaps because its most famous member, the late Edward Said, had lauded Paulin for being “a reader of almost fanatical scrupulosity.”

At Harvard the dispute over Paulin became one about free speech or “hate speech” or (perhaps) the constitutional right of a British subject to have an endowed lectureship bestowed on him in America. (Britain does have a surplus of such people.) After much tumult, the English faculty, with the blessing of Harvard president Lawrence Summers, rescinded its invitation to Paulin. But then the school’s civil liberties absolutists weighed in on behalf of Paulin’s “right” to lecture, and the English faculty reinvited him. (Some urged that he should be encouraged to speak because they were confident that his egregious stupidity would expose him to deserved ridicule and keep him from wallowing in the [painless] martyrdom he sought.)

The deeper significance of the Paulin affair was revealed, unintentionally, by Shakespeare scholar Professor James Shapiro, one of Columbia’s most ardent defenders of a Paulin appointment. Casting his eye over Paulin’s oral and written remarks about shooting Jews dead and destroying their country, Shapiro declared that they “did not step over the line.” Apparently Shapiro’s dividing line is like the receding horizon; he walks toward it, but can never reach it. The real question—not whether Paulin should be reciting poems at Harvard or tutoring students at Columbia but whether or not he should be in Reading Gaol [Jail] (like an earlier and much better Oxford poet named Wilde)—was almost entirely ignored.

Public discourse about Jews and Israel had now crossed a threshold: the dividing line between the permissible and the possible had been erased. In the following months writers and publications that had long been hostile to Israel did, in more “civilized” and literate form, what Paulin had already done in his unkempt Yahoo style: they moved from strident criticism of Israel to apologias for antisemitic violence and calls for dissolution of the country. The liberal UC Berkeley historian Martin Jay (in Salmagundi, winter/spring 2003) merely blamed Jews for “causing” the “new antisemitism; but Paul Krugman (Princeton) went a step further (New York Times, October 23, 2003) by “explaining” (away) the Malaysian Mahathir Mohamad’s regurgitation of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion as “anti-Semitism with a Purpose”; and then the liberal historian Tony Judt (NYU) outdid both of them in the New York Review of Books (October 23, 2003)—the Women’s Wear Daily of liberal academics–by calling for the end of the State of Israel as the panacea for the ills of the world. It was Judt’s call for politicide that provoked the invention (by David Frum) of the term that has provided Cravatts with the title for his important book.

Edward Alexander’s new Book, THE STATE OF THE JEWS: A Critical Appraisal (NJ, Transaction Publishers,), is scheduled to appear in May.

Comments are closed.