The Four Great Waves of Defense Neglect by PETER HUESSY ****

If an additional $50 billion a year seems like a lot, how much would be the cost to the United States if adversarial nations continue to chip away at the free world until America finds itself either isolated or impotent to effect a reversal as it faces rogue terrorist states armed with the most deadly of weapons?

America’s fourth wave of neglect of its military since the end of World War II may have disastrous geostrategic consequences.

While Congress has passed a temporary slowdown in the decline in American defense spending with a two-year budget framework, the Ryan-Murray budget agreement, which restores $32 billion to the Department of Defense, the projected defense resources available for the next eight years will not allow the United States to protect its own security, let alone that of its allies.

Taken together, as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff warned[1], previous and projected cuts to military budgets from 2009-2023 threaten dangerously to undermine the stability required for both economic prosperity and relative peace among the world’s major military powers, as well as America’s global standing.

One of the nation’s top defense analysts sums it up: “The reality is, for all its promise, the Ryan-Murray budget agreement still only addresses less than 7 percent of the defense sequester. Much more work needs to be done to lift the specter of sequestration once and for all …”[2].

THE FIRST WAVE OF NEGLECT, 1945-1950

After World War II, U.S. security suffered. The decline in defense spending after 1945 was large, $90 billion down to $14 billion at the beginning of the first year after the war’s end (FY1947 or July 1, 1946). With the end of World War II, support for a strong US military was not a sure thing.

While the Marshall Plan, or European Economic Recovery Plan, did stop a significant portion of the planned expansion of the Soviets into Europe[3], these efforts consisted primarily of significant American economic assistance and the transfer of surplus military equipment to designated countries, with some American personnel transferred for training purposes as well – but without the deployment of American soldiers[4].

Despite the success of the Marshall Plan, however, serious security threats remained in the post-WWII period. The communists threatened to come to power in Turkey and Greece and succeeded in taking power in Czechoslovakia in February 1948 — a move, it was feared, that would imperil the freedom of other states of Europe.

A few months later, on May 15, 1948, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Syria, after rejecting the UN supported partition plan, invaded Israel, an attack that set off what is now 75 years of continued attempts to displace or destroy the Jewish state.

The next month, on June 24, 1948, the Soviets imposed a blockade on West Berlin. According to Lucius Clay, the military governor of the American zone of occupied Germany: “When the order of the Soviet Military Administration to close all rail traffic from the western zones went into effect at 6:00AM on the morning of June 24, 1948, the three western sectors of Berlin, with a civilian population of about 2,500,000 people, became dependent on reserve stocks and airlift replacements. It was one of the most ruthless efforts in modern times to use mass starvation for political coercion…” A top secret document at the time described the Soviet action as the first act of the new Cold War.

Many observers believe the Soviet action actually backfired: they sped up the establishment of the new Federal Republic of Germany and helped spur the April 4, 1949 creation of NATO. A month later, in May, the Soviets lifted the Berlin blockade.

Elsewhere, however, the situation did not improve. On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union exploded its first nuclear weapon. A little more than a month later, on October 1, 1949, China fell to the communists under Mao Zedong.

Despite the creation of NATO, the emerging Cold War, and the Soviets’ explosion of a nuclear weapon, American defense spending continued to be neglected, dropping to $13.5 billion by July of 1950, — a full 7% cut from the year before. During 1947-49, the first Secretary of Defense, James Forrestal, continually fought the Truman administration’s interest in cutting defense to as low as $7 billion annually, a number supported by strong isolationist elements in Congress.

As a result of opposition within the Truman administration to Forrestal’s support for a strong defense, he resigned March 1, 1949. The new Defense Secretary, Louis Johnson, was, unlike Forrestal, all for cutting defense. Under his watch, 80% of the “needed equipment” purchases for the Army were postponed — a delay which, as the administration testified to Congress, “would make the Army force levels…more effective[5].

In an echo of subsequent American political debates over the next half century, the new Secretary of Defense and the Truman administration apparently saw large government spending–including defense spending– as bad for the US economy. After all, the 1945 recession caused GDP to fall a whopping 10.6%, and even by 1949 another recession hit while unemployment reached 7.9% and GDP fell 0.5%.

In December 1949, for example, to justify further defense budget cuts, then Defense Secretary Louis Johnson told the commander of the U.S. Atlantic and Mediterranean fleet, Admiral Richard Conolly: “Admiral, the Navy is on its way out. There’s no reason for having a Navy and a Marine Corps. General Bradley tells me amphibious operations are a thing of the past. We’ll never have any more amphibious operations. That does away with the Marine Corps. And the Air Force can do anything the Navy can do, so that does away with the Navy.”[6]

Unwilling to strengthen the U.S. military even in anticipation of the need to help its new NATO allies, the Truman administration tried a different tack. It asked Congress to provide economic security funding for its friends in Greece, Turkey and, early in 1950, South Korea, rather than to reinforce our own military forces to provide these allies a stronger security umbrella.

Although Greece and Turkey were successfully helped with approval of assistance by the Congress, passage of similar but much smaller legislation to help Korea failed in the House by one vote, leaving America’s Korean allies without U.S. backing.[7]

This failed effort to assist the Republic of Korea was followed by remarks delivered by Secretary of State Dean Acheson in early 1950. He said that for American purposes, South Korea was beyond its security perimeter, a remark that many would later interpret as a careless and implicit invitation for would-be aggressors to invade South Korea.[8]

To be fair, Acheson added that the UN could be relied upon “to protect a nation’s security” but then compounded his original comments by asserting that whatever problems were faced by East Asia, “any guarantee against military attack is hardly sensible.”[9]

This assessment followed an intelligence report to the President that concluded North Korea might invade the Republic of Korea [ROK], but that it had no capability to invade its southern neighbor without the assistance of the Soviets. That assessment, in turn, led to the further conclusion among members of the intelligence community that no such threat existed for some number of years because Moscow was not going to sanction such aggression. (See Intelligence Memos #302-06 referenced below).

America’s problems were not limited to just intelligence failures. By 1950, Defense Secretary Johnson “had established a policy of faithfully following President Truman’s defense economization policy, and had aggressively attempted to implement it even in the face of steadily increasing external threats posed by the Soviet Union and its allied Communist regimes. He consequently received much of the blame for the initial setbacks in Korea and the widespread reports of ill-equipped and inadequately trained U.S. forces.”[10]

Further, Secretary Johnson’s “failure to adequately plan for U.S. conventional force commitments, to adequately train and equip current forces, or even to budget funds for storage of surplus Army and Navy war-fighting materiel for future use in the event of conflict would prove fateful after war broke out on the Korean Peninsula”.[11]

Compounding U.S. problems was that the Truman administration assumed that the U.S. monopoly on atomic weaponry would preserve American and allied security and not require a major increase in conventional military investments.

What the U.S. intelligence community did not know was that, as Julius Rosenberg had delivered American atomic secrets to Moscow, the Soviets had received critical help to build an atomic weapon.

Thus, long before the U.S. intelligence community thought possible, the Soviets successfully tested a nuclear weapon in August 1949, an accomplishment that was most certainly a factor in the decision of the Soviet Premier, Josef Stalin, to support the invasion of the Republic of Korea by the North – an act that the U.S. intelligence community was convinced the Soviets would not do.[12]

Apparently, as archival material implies, Stalin was convinced the U.S. would not respond to help the Republic of Korea, and, like the leader of North Korea, Stalin saw the “liberation” of China as simply a prelude to the “liberation of South Korea.”[13]

In short, the U.S. intelligence community knew that Moscow had exploded an atomic device, but, even after the outbreak of the Korean war, did not seem to integrate the new circumstances into its intelligence assessments.

On July 8, 1950, for instance, some two weeks after the North Korean invasion[14], the Truman White House received an intelligence brief concluding that “Soviet intentions in supporting the Korean invasion were unknown.”

As for possible future Chinese involvement in the war, the memo stated that, “…movements of large troop formations from South and Central China toward [North Korea] are largely discounted.”

It appears likely, therefore, that the post-World War II defense neglect, coupled with erroneous intelligence assessments, played a key role in the lack of readiness of U.S. forces as they came to the rescue of the ROK in 1950.

It is also likely that the excessive drawdown of U.S. military spending within the Truman administration in the immediate post World War II period sent the wrong signals to America’s adversaries, as well as harming U.S. military readiness.

Further, the less-than-stellar Truman administration’s verbal support for the Republic of Korea, as well as the failure of Congress to supply the ROK with even a small amount of economic assistance, may also have led Stalin to conclude that an invasion of the ROK would not be contested by the United States.

Yet, despite massive shortages of equipment and serious readiness deficiencies, the US eventually saved the ROK from communist tyranny, but only at a cost of 35,000 American lives and those of an estimated 5 million Koreans.

Ironically, parallel to this policy of neglect, pro-military forces within the Truman administration sought to put together for America’s role in the world, a strategic vision and plan that would confront the threat of a nuclear-armed Soviet Union. This objective became an imperative for these administration people, particularly after the Soviet test-explosion of a nuclear weapon in August 1949.

Even then, the Secretary of Defense at the time, Louis Johnson attempted to dismiss the nuclear radiation from the explosion as the result of an industrial accident, and not a real weapons test[15].

Thw new strategic vision was codified in a new national security defense directive (NSDD 28), which recognized the extraordinary threat to America and its allies from a nuclear-armed Soviet Union — no longer the partner with which the allied forces had won World War II.

The primary author of the report was Paul Nitze, later the founder of the Committee on the Present Danger, which, in three separate instances (1950, 1976 and 2004) would warn Americans that the threats it then faced were deadly and could not continually be ignored.

Shortly after Nitze’s NSDD was formally adopted by the Truman administration in April 1950, President Harry S. Truman was told that such a national security policy would also require an estimated $41 billion a year in DOD spending for its implementation.

When contrasted to the then $13-14 billion defense budget, the implications were serious. How could the Truman administration support a security policy that implied the need for a defense budget 300% higher than its own supported defense program?

On June 25, 1950, North Korea’s invasion of the ROK ended the debate. By mid-1951, defense spending reached $24 billion a year, peaking at $44 billion in 1953. After the Korean War ended, the war effort spending-level was significantly cut and the defense budget fell from $44 billion to $36 billion.

Despite the defense budget gradually increasing to $43.1 billion by the end of the decade (FY61 budget), President Dwight Eisenhower, was routinely criticized by both Democrats on Capitol Hill and the defense industry for shortchanging defense. The final defense budget passed under the Eisenhower administration at $43.1 billion (1953-61), was just $2 billion,or 5%, below the $41 billion budget (adjusted for inflation) that had been recommended by the Truman administration’s NSDD28 for 1950.

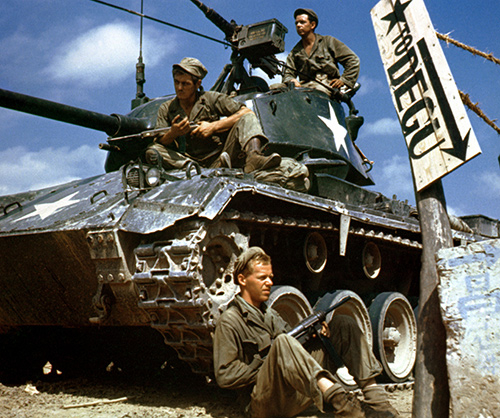

The Korean War ended the first wave of defense neglect. Pictured above, a U.S. tank crew in Korea, August 1950. (Image source: U.S. Dept. of Defense) The Korean War ended the first wave of defense neglect. Pictured above, a U.S. tank crew in Korea, August 1950. (Image source: U.S. Dept. of Defense) |

The Eisenhower administration, however, relied on American nuclear weapons for a policy of nuclear massive retaliation in the event of Soviet aggression, a policy thought to be considerably less expensive to implement than an alternative that emphasized conventional capabilities.

To that extent, the critics were right: U.S. conventional military strength did not match that of the Soviets. But to increase American and allied conventional weapons, and match the Soviet and Warsaw Pact conventional forces tank for tank, and artillery piece for artillery piece, would have cost the United States and its allies tens of billions in additional annual defense expenditures that the Eisenhower administration and its allies were unwilling to support.

THE SECOND WAVE OF NEGLECT, 1970-1980

The communists in the Kremlin, evidently deciding that, given America’s and its allied forces’ commitment to “contain” Soviet-led aggression, cross-border wars such as Korea were not likely to succeed, adopted, instead, supporting smaller, more containable guerrilla wars, popularly known as “wars of national liberation.”

According to the Assistant Secretary of State for the Far East, William P. Bundy, Cuba, Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America had become targets for subversion[16].

To counter, in part, this Soviet campaign, American military spending increased from $43 billion when President John Kennedy was elected in 1960, to $51 billion in the 1964 election year, and from there to a peak of $83 billion in 1969 at the height of the Vietnam War. Tragically, the war was especially divisive, partly due to its length but primarily because of the high casualties the U.S. sustained without any compensatory sense that the war was being won.

Although many experts believe the South Vietnamese and Americans had won the war by 1969, the American withdrawal — followed by the abandonment of our Saigon allies by Congress in 1975 — led to the fall of the South Vietnamese government and the imposition of communist rule there and throughout Indochina.

After the United States disengaged from the Vietnam War, and the war costs came to an end, defense spending declined and remained relatively flat for half a decade. Fueled by an intense anti-military sentiment in Congress and among the public at large, so began the second major period of U.S. neglect of its armed services since the end of World War II.

Ironically, after 1975, the defense budget increased by nearly 60% over its 1969 peak. But for three important reasons, in real terms, even these increasing defense budgets were still significantly underfunding the country’s defense needs.

The first reason was the cost of paying U.S. soldiers. Although the nation had moved to an all-volunteer military in 1973 under the assumption that absent a draft, future “unpopular” wars such as Vietnam would be impossible to fight, because few would volunteer for such wars (thus reducing defense costs significantly), the proponents of an all-volunteer force failed to anticipate the high personnel costs required to attract such recruits.[17]

Thus, between 1971-5, basic military pay doubled in real term costs, just as the country was transitioning to an all-volunteer military — in addition to significant costs associated with attracting sufficient soldier volunteers to join the military.

The second key reason was inflation. The Nixon, Ford and Carter administrations all sought to monetize the national debt by first taking the country off the gold standard and then printing money to pay for U.S. deficit spending. Inflation, which reached 14% a year by 1980, required an increase in defense spending of nearly $20 billion for that year alone, just to keep pace with increased costs.

The third reason was dramatically higher oil prices. The proximate cause was the downturn in Iran’s oil production after the 1983 oil embargo and the fall of the Shah of Iran. These circumstances caused two recessions (1974-5 and 1980-1), with retail gasoline prices climbing from $0.36 cents a gallon in 1973, to $0.62 cents in 1978, and to $1.18 by 1981.

Therefore, at the same time as inflation accelerated, the country fell into two recessions, a combination that came to be known as “stagflation.” It had the effect of increasing the cost to the military for the fuel it used; the cost of military hardware and personnel, due to higher inflation; fueling international tensions, particularly in the Middle East, further stretching U.S. military requirements; and finally, reducing U.S. economic growth and subsequent revenues to the Treasury a combination that increased budget pressures on defense resources just as requirements for greater defense capabilities were on the rise.[18]

As a result, during the 1970s this combination of factors serially delayed the acquisition major weapons systems, including, for example, needed airlift, fighter aircraft, space, nuclear deterrent and army ground combat assets. Research and development funding also failed to keep pace with modernization needs. In short, just as costs to maintain the military were going up (personnel, hardware and fuel), the surge in inflation wiped out any real purchasing power of the modest defense budget increases that were finally adopted during the last five years of the decade.

In addition to these cost pressures, the armed services were also suffering from expansive drug and alcohol abuse, desertions and bad morale. Former Secretary of State and retired General Alexander Haig told this author that, while commander of all allied forces in Europe (SACEUR 1974-1979), as a result of these negative pressures, he had to struggle to keep the military from falling apart.

These factors, when added together, created what came to be described as the “hollow army”.

The resultant cost to American security was high. Modernization was delayed, deferred or abandoned, including tactical aircraft, airlift, nuclear forces and ground combat force technologies.

In 2013, the current Army Chief of Staff, General Raymond Odierno, warned that the U.S. might be repeating the same mistake: “I know what is required to send soldiers into combat. And I’ve seen firsthand the consequences when they are sent unprepared…I began my career [referring to the 1970’s] in a hollow Army. I do not want to end my career in a hollow Army.”

As United States military spending in the 1970s failed to keep pace with U.S. security needs, nation after nation fell to communism or totalitarianism, including South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Grenada, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Angola, Bangladesh, Chile, and Iran.

Soviet sponsored terrorism grew rapidly as Moscow joined forces with Syria, Libya, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam and other terrorism-sponsoring states, as well as their new terrorist creations such as the Palestinian Liberation Organization [PLO]; the communist guerrillas in El Salvador, known as the FMLN, and terror groups such as Italy’s Red Brigades and Germany’s Baader-Meinhof Gang in Europe.

American military action in Cambodia to rescue the freighter Mayaguez (May 1975) and the loss of soldiers in Desert One during the attempted rescue of U.S. diplomats in Iran (April 1980) were less than exemplary bookends to the neglect of America’s military in the post-Vietnam era. According to the Soviets, the “correlation of forces” [COF] in the decade of the 1970s had decidedly moved in their direction.

As Mackubin Owen explains: “Indeed, the Soviet military press during this decade was filled with numerous references to the COF. For instance in 1975, General Yevdokim Yeogovich Mal’Tsev wrote that “the correlation of world forces has changed fundamentally in favor of socialism and to the detriment of capitalism.”[19] An insight onto the thinking of the time is illustrated by former President James Carter’s boast that at the end of his Presidency (1981) his proudest accomplishment was never having used American military forces in combat. As the former President himself put it: “We never dropped a bomb. We never fired a bullet. We never went to war”.[20]

THE THIRD WAVE OF NEGLECT, 1991-2000

The third wave of neglect came at the end of the Cold War –ironically, after the success of the American military in Desert Storm. The country and many of its leaders appeared to have decided that peace had broken out, threats were gone, and we could all safely go to the beach. Some described this period as “the end of history,” or, as Charles Krauthammer more accurately put it, “a holiday from history.”[21]

In the National Interest, Summer 1989, “The End of History,” Francis Fukuyama wrote: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”[22]

It is not that such an outcome would certainly be preferable to the Cold War. What made Fukuyama’s essay terribly flawed was the assumption that even should “totalitarianism return,” as he noted, he assumed democracy would somehow still become more prevalent.

What was missing was an acknowledgment that each generation, if unwilling to protect its freedom, could in fact readily lose its freedom, as President Reagan warned us on January 11, 1989 in his farewell address to the nation:

“Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn’t pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected, and handed on for them to do the same, or one day we will spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children what it was once like in the United States where men were free.”

Thus, after the end of the Cold War, and coincidentally right after the U.S. and coalition victory in Desert Storm, U.S. defense spending declined between 1989-2000 by a cumulative $1 trillion according to former Senator Sam Nunn, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee,1987-95.

This decline after the end of the Cold War was most serious in the procurement accounts, where the U.S. apparently decided to go on a holiday and “forget the farm,” so to speak.

According to remarks made in December 2000, former top Department of Defense official John Hamre, currently the highly regarded President of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the overall decline in the acquisition accounts meant that fully 40% of the equipment which the Clinton administration had committed to buy during its two terms was never purchased.

Purchases were also deferred or cancelled for much of the nuclear deterrent accounts, in which the U.S. neglected key sustainment and modernization efforts across the board. One bright spot was that all 500 Minuteman missiles underwent a service life extension effort, which is now just concluding.

The serial delay in weapons purchases, however, pushed modernization efforts well into the future – with the result that enormous cumulative modernization requirements became due simultaneously, just at the time when the U.S. ended up fighting in both Afghanistan and Iraq, and as it pursued the “global war against terror” — while leaving to it to the future to determine if funds would be available to carry out all these tasks.

This second wave of neglect in the 1990s was somewhat ameliorated, starting in 1995, by defense supporters in Congress. Each year from 1995-2000, they added between $8-15 billion to the defense accounts beyond the administration’s budget requests, helping to keep the defense acquisition accounts from cratering.

As a result, the defense budget was nominally at the same level of spending in 2001 as it was in 1991, thereby avoiding a prolonged “defense trough” in which modernization would have been even more greatly affected. The very modest “mini-defense-buildup” from 1996-2000 was done, ironically, even while Congress also cut capital gains taxes, reformed welfare, balanced the budget and paid down the U.S. national debt by hundreds of billions of dollars.

Although the Cold War ended in 1991, dangers did not disappear: America was repeatedly attacked by terrorists throughout the 1990s, culminating in the attacks of September 2001.

As historians Donald and Frederick W. Kagan argued in their book, “While America Sleeps: Self-Delusion, Military Weakness, and the Threat to Peace Today,” the policies of the previous administrations had left the U.S. in a position “where we cannot avoid war and keep the peace in areas vital to our security”.

One review put it: “Neither have the post-Cold War policies sent clear signals to would-be aggressors that the U.S. can and will resist them. Tensions in the Middle East, instability in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan, the development of nuclear weapons and missiles by North Korea, and the menacing threats and actions of China, with its immense population, resentful sense of grievance and years of military build-up, all hint that the current peaceful era will not last…are we prepared to face its collapse?[23]

The new administration under President George W. Bush had been hopeful that new technologies could help enhance our defense capabilities and make them more effective but without necessitating a huge build-up in defense spending.[24]

The previous decade of neglect, however, was taking its toll: personnel costs were starting to balloon — as were operations and maintenance accounts — just when modernization costs were starting to escalate, having accumulated from over a decade of delay and “kicking the can down the road.”

With the attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent liberation of Afghanistan from the Taliban and Iraq from the Baathist Saddam Hussein regime, U.S. defense spending for these overseas deployments dramatically increased the overall defense budget just as average personnel costs climbed and modernization needs mounted. The defense budget doubled from 2001-8, and so did personnel costs. While much modernization did take place, the costs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the general toll on American forces deployed in the global war against terrorist threats, left the modernization job undone.

THE FOURTH WAVE OF NEGLECT 2009-????

With new administration in 2009, the paramount effort was directed at ending the war in Iraq as soon as possible, and to begin a drawdown of American forces in Afghanistan. Beyond these two top goals, however, the country did not really have an extended debate as to what the future size of the U.S. military should be.

The country also did not have any serious debate about America’s proper role in the world, nor which alliances needed strengthening. America’s focus turned almost entirely to getting American troops out of Iraq and Afghanistan — popularly termed “ending our wars” — and “stopping Al Qaeda and its affiliates” — again, without debate as to what that meant beyond finding and killing Osama Bin Laden.

Once the current U.S. administration decided to withdraw from Iraq and Afghanistan, instead of simply cutting the funding from these “overseas contingency operations,” as the administration labels overseas military deployments, it began making significant additional cuts in America’s defense spending. These cuts have been, and are, extremely large and have continually been described by many in the nation’s senior military and civilian leadership as inconsistent with maintaining America’s security.

Starting in 2009, the current administration cut hundreds of billions from future defense spending accounts, known as five year defense plans, which every administration submits and updates annually. That number has now reached in excess of $2.5 trillion or fully 30% less than the projected spending laid out in the last defense plan of the previous administration and the initial 2009 plan of the current administration.

Not counting war costs, the administration cut $300 billion in its first budget, compared to the plan it inherited from the previous administration. This cut was followed by an additional $175 billion in “efficiency” cuts from its own 2009 budget, cuts to be initiated in 2010-11. That was followed by another $487 billion in defense spending cuts as part of the ten year deficit reduction agreement of 2011.

Finally, the current sequestration law required another $550 billion in cumulative defense spending reductions by 2022. Although that has now been slightly reduced by $32 billion over the next two years (by virtue of the Senator Patty Murray-Congressman Paul Ryan budget agreement of December 18, 2013, signed into law by the President).[25]

At the same time these budget cuts were being implemented, the U.S. was also withdrawing from Afghanistan and Iraq, but although the cost of those wars declined sharply, the figures for them are kept in a separate budget category known as “overseas contingency operations” or OCOs.

Many observers believe the budget cuts referenced here belong to these reductions, and their reaction often seems quite reasonable: as we withdraw from Afghanistan and Iraq, the defense budget is going to be reduced, so what is the problem?

When the administration came into office such OCO costs were $158 billion annually. They are now at $90 billion – an annual cut of $68 billion, or over one third. Over the next decade, the cuts are projected to reach another cumulative cut of $550 billion as overseas U.S. military counter-terrorism operations diminish. But all of the cuts discussed above are in addition to the reductions in the OCO war costs.

When taken together, therefore, the defense budget and OCO spending reductions since 2009, and projected through 2022, will reach $2.5 trillion, (including the interest saved by not otherwise borrowing the funds).

Why is this important?

This rather lengthy assessment of the defense budget is needed to explain the full context of the changes made to the defense budget of the United States since 2009, and to understand fully the growing opposition to the ten-year automatic across-the-board sequestration of defense spending required by the 2011 budget agreement.

No other part of the Federal budget has undergone such reductions, which, in defense, will approach 30% since 2009. All other Federal budget areas have, in fact, grown, often dramatically, especially means-tested poverty programs and entitlements.

Further, the OCO spending reductions cannot be counted toward the required automatic sequestration defense cuts of $1 trillion agreed to in the 2011 budget agreement.

And, most worrisome, there is no defense strategy document from the administration that connects the defense budget spending levels required by sequestration and our security needs. [The administration will be issuing a new defense strategy in the spring of 2014; it may make this connection].

Although wars are not won or crises averted by just throwing money at defense spending, national security leaders have repeatedly underscored that these required cuts will undermine and dismantle key defense capabilities required for our security.

For example, the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Howard P. “Buck” McKeon, noted on February 14, 2012, while discussing the budget cuts with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, “You concluded, General Dempsey, that this new strategy would, and I quote, ‘not meet the needs of the nation in 2020 because the world is not getting any more stable.'”[26]

The Department of Defense website contains dozens of articles detailing the same problems, such as, “Acquisitions chiefs from each of the military services described the devastation being wreaked upon their branches by [defense sequestration cuts]” while “The nation’s service chiefs have told Congress if budget sequestration extends into fiscal year 2014, forces, capabilities and readiness will all be slashed, reducing the security of Americans.”[27]

Defense experts have emphasized that when one calculates the numbers, should all the defense budget cuts materialize through 2022, the U.S. will field, at the end of this decade, the smallest Navy since World War I, the smallest air force U.S. history and an Army smaller than that just before World War II.

According to a recent DOD testimony, only two Army brigades are combat-ready at this time; flying hours for the nation’s Air Force are being dramatically reduced, and ships are less combat-ready than at any time during the past 40 years.

In an echo of the 1970s, Frank Kendall, the acquisition chief of the U.S. Department of Defense, warned in November 7, 2013 that the defense cuts of $550 billion over the next ten years, imposed by the budget cuts of the automatic sequestration, will “leave the Defense Department with a hollow force and debilitating shortfalls”.[28] Specifically, key modernization elements such as nuclear missiles, tactical aircraft, strategic bombers, ship building, space reconnaissance, cyber counter-warfare, and missile defense will be cancelled or seriously reduced in scope.

The budget deal, as passed by Congress on December 18, 2013 in the House, and now the Senate, restores some $32 billion of roughly $100 billion in cuts over the next two years. Other spending and revenue reforms, including small cuts to mandatory entitlements, make up the difference. [Provisions to trim cost-of-living adjustments for veterans will be repealed, I believe, in the next Congress, perhaps as part of a military and defense personnel reform package].

Whatever one may think of the admittedly modest Murray-Ryan budget agreement, it avoided the $1 trillion in both new taxes and spending proposed by, and approved by, the Senate budget committee while keeping 70% of the sequestration cuts. The agreement also traded some of the defense spending increases for cuts in other spending, including a small portion of mandatory or entitlement spending.

True, there are, of course, major required additions, such as tax and entitlement reform that need to be completed but that were not included. Tax reform — such as the 1986 tax reform agreement — that generates more federal revenue because of greater economic growth, could offset defense cuts required by sequestration and ultimately generate revenue to bring the budget into balance.

The administration has been clear that, as noted, the projected defense spending cuts are seriously going to harm national security; and there is widespread, but by no means unanimous, agreement on both sides of the political aisle that defense will be seriously harmed by continued budget cuts.

Much of the argument has consisted of protests that tax revenues are simply not adequate to sustain defense spending at the level defense leaders want, so the conclusion becomes that defense spending must continue to be sharply cut, whether a wise idea or not, because first, the deficit has to be narrowed and second, there is no agreement to reduce the bulk of government spending elsewhere, such as in the entitlement and poverty program accounts.

Tax revenue, however, has been increasing dramatically, and for the first time since the end of the previous Bush administration. Last year alone, tax revenue rose dramatically by close to $300 billion, although some significant amount of this increase is due to “one time” elements such as the end of the payroll tax holiday, TARP repayments and mortgage-related fees.

But with an economy that grew, revenue growth, as well, could be significant. Between 2003-7, annual revenue to the government rose from $1.7 trillion to $2.56 trillion, an annual increase of $850 billion — an increase never previously achieved. The increases during 2004-7 were for an economy 10% smaller than today’s, but with faster GDP growth increase and lower tax rates.

So why couldn’t a larger economy, with faster economic growth than today’s, raise sufficient revenues to pay national bills? To claim, as many have, that somehow Republicans are “against revenue increases” and thus unwilling to compromise on a budget deal misses by a wide mark that there is common ground.

A year ago, the administration was adamant that Republicans must raise tax rates to raise revenue, rather than to expand the economy.[29] In a hopeful sign, Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia acknowledged as much in a discussion on Fox News, when he said that said one could raise revenue by expanding the economy and putting people to work, rather than by raising tax rates, and that such a framework could be used to put together an agreement.

CONCLUSION

This is the fifth year of the fourth wave of neglect since World War II. Extending it further risks significantly undermining American security, as a review of recent headlines attests:

Russia is deploying nuclear armed Iskander missiles near the Baltic states and Poland.[30]

China continues to expand its military presence in the South China Sea, seeking to intimidate its neighbors as well as the United States, while adding to its military capability long range nuclear capable bombers, ICBMs and SLBMs.

Egypt is now seeking billions in military equipment from Russia, in the biggest arms sale since the 1970’s; part of an effort by Russia, in their words, to “exploit the waning power of the United States.”[31]

According to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Martin Dempsey, “Iran is a threat to national security in many ways. We have been very clear as a nation we are determined to prevent them from acquiring a nuclear weapon because it would be so destabilizing to the region. But they are also active in cyber. They’ve got surrogates all over the region and all over the world. They proliferate arms.”[32]

Such threats are becoming increasingly serious. To counter them, the U.S. needs to reverse the sequester, which threatens to cut an additional half trillion dollars from America’s security resources over the next decade. To do so would require finding $50 billion annually to offset annual defense spending cuts from an annual federal budget now close to $3.7 trillion, and projected to reach $5.5 trillion in ten years.

The total amount comes to 1.35% of all federal spending, or $1 out of every $74 the U.S. now spends each year.

Or the equivalent of 0.94% of all federal spending 10 years from now ($1 out of every $104 the U.S. would spend at that time).

Three previous waves of neglect ended first with the Korean war and 35,000 dead Americans; second with the Soviet Union on the march convinced the “correlation of forces” were moving their way; and the third, with the rise of Islamist state-sponsored terrorism, which culminated in 9/11, and which in the future may consist of many states, failed and otherwise, armed with nuclear weapons.

If an additional $50 billion a year still seems like a lot, how much would the cost be to the United States if adversarial nations continue to chip away at the free world until America finds itself either isolated or impotent to effect a reversal as it faces rogue terrorist states armed with the most deadly of weapons?

Notes

[1] “Chairman Outlines Sequestration’s Dangers,” by Claudette Roulo, American Forces Press Service, Washington, Feb. 13, 2013.

[2] “Punting on the Pentagon Budget”, by Mackenzie Eaglen, US News and World Report, December 13, 2013.

[3] NY Times, April 1, 2010, “Harry S. Truman, Decisive President.”

[4] “Truman Acts to Save Nations From Red Rule”, by Felix Belair, Jr., New York Times, March 12, 1947.

[5] See LaFeber, Walter, America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1980, 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill 1993

[6] See Vincent Davis, “The Post-Imperial Presidency;” “The Anti-Defense Secretary,” by Mackubin Thomas Owens, The Weekly Standard, January 28, 2013 and Krulak, Victor H. (Lt. Gen.), First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps, Naval Institute Press (1999)

[7] SparkNotesEditors, The Korean War 1950-1953.

[8] Speech by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, National Press Club, January 12, 1950

[9] Ibid

[10] Blair, Clay, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953, Naval Institute Press, 2003

[11] Ibid

[12] “The Korea Times”, May 16, 2012, essay by Professor Andre Lankov, “Soviet Leader Approved Invasion Proposal”.

[13] See for example “Mao, Stalin and the Korean War” by Shen Zhihua, June 12, 2012, which analyzes all these issues in some detail.

[14] See “Intelligence Memorandum, #302-06“, for the study of intelligence.

[15] See for example “Fulcrum of Power: Essays on the USAF and National Security: Part V” by Herman Wolk.

[16] Dallas Council on World Affairs, May 13, 1965, “Reality and Myth Concerning South Vietnam”.

[17] “CSBA: “Military Manpower for the Long Haul”, 2008.

[18] WTPG Economics, 1996-2011 by James C. Williams, and “The Recessions of 1973 and 1980 Caused by High Oil Prices,” by Robert Lenzer, Forbes, September 1, 2013.

[19] February 2004, Mackubin Owens, “The Correlation of Forces”, Ashland University, Ashbrook Center.

[20] Carole Cadwalladr, “Jimmy Carter: ‘We Never Dropped A Bomb”, The Observer, September 10, 2011.

[21] Charles Krauthammer, “Holiday From History”, The Washington Post, February 14, 2003.

[22] Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History, The National Interest, Summer 1989.

[23] McMillan Press Review, November 2001.

[24] Professor Norman Imler, “How Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld Sought to Assert Civilian Control Over the Military, National Defense University Press, 2002.

[25] All these budget numbers are from www.usgovernmentspending.com, a private website with the finest compilation of government budget, tax and spending data available anywhere.

[26] Transcript of the February 14, 2012 House Armed Services Committee Hearing, “Impact of Sequestration on the Defense Department”.

[27] “Service Chiefs Detail 2014 Sequestration Effects”, By Cheryl Pellerin, September 19, 2013, American Forces Press Service and “Acquisitions Chiefs Describe Effects of Budget Uncertainty”, by Claudette Roulo, American Forces Press Service, October 24, 2013.

[28] Frank Kendall, “Sequestration Will Make Hollow Force Inevitable”, November 7, 2013, American Forces Press Service.

[29] Yahoo News, December 4, 2012, “Republicans Must Raise Rates”, by Rachel Rose Hartman.

[30] New York Times, “Deployment of Missiles Is Confirmed by Russia”, December 16, 2013.

[31] UPI, “Russia Offers Egypt MidG-29s in $2B arms deal”, November 15, 2013.

[32] The Tower Magazine, June 12, 2013, “Iran A Threat to National Security”.

Read more: Family Security Matters http://www.familysecuritymatters.org/publications/detail/the-four-great-waves-of-defense-neglect#ixzz2uQVXhhsp

Under Creative Commons License: Attribution

Comments are closed.