Israel’s So-Called Poverty Problem OECD Poverty Lines Do Not Define Poverty by Malcolm Lowe

https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/9894/israel-poverty

- According to the OECD definition of the “poverty line,” you can make everyone fabulously rich while keeping them all as poor as before. But you can eliminate poverty by reducing them all to starvation levels.

- Assume that large differences between OECD countries in alleged “child poverty” may, nevertheless, have some significance. The consequence of this assumption, however, is that Israel is doing better than numerous other OECD countries when the uniquely high fertility rate in Israel is taken into account.

- It was a real achievement to raise the employment rate of single mothers from 66% to 81%. To insist that nothing has changed because the same proportion of such families remains below the so-called poverty line is both wrongheaded and could discourage attempts to improve the situation further.

- It is sometimes thought to be paradoxical that Israel features so highly in the “World Happiness Reports” – at 11th place out of 157 countries in the latest report. There is no paradox if such factors as joy over having children and pride at being in work outweigh artificially defined poverty.

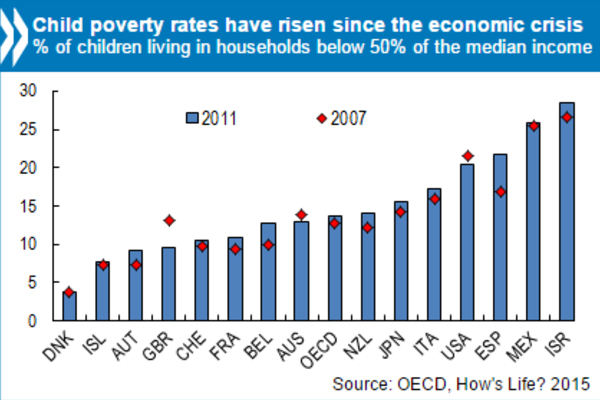

Israel joined the “Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development” (OECD) on September 7, 2010. Since then, Israel has featured in the OECD’s annual reports. Every year we are told that “Israel’s poverty rates are highest among OECD nations,” as again in 2016. Especially bewailed are figures about “the proportion of children living in families below the poverty line.”

There are, of course, poor families in Israel. Any social worker dealing with families can name some. The question is whether the OECD reports provide information that can serve to deal with such poverty as exists. The answer is negative because OECD “poverty lines” are falsely construed as measures of poverty. They define, instead, something quite distinct from poverty: income disparity.

This absurd discrepancy is revealed in a little Wikipedia article on “Measuring Poverty,” where we are told:

“The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is a relative poverty measure based on ‘economic distance,’ a level of income usually set at 60% of the median household income.”

To be exact, the OECD sets the level at 50%. In one place, its website states:

“The poverty rate is the ratio of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population.”

By the “median household income” is meant the level of income such that half of households are above that level, and the other half below it. (In another place, as we shall see, the OECD website offers two distinct definitions of the poverty rate, of which this is the second.)

The OECD website does, however, immediately go on to note that “two countries with the same poverty rates may differ in terms of the relative income-level of the poor.” Now, if one cannot give two countries the same rating on the income-level of the poor even when they have the same OECD poverty rate, how can any comparison of poverty rates between countries tell us anything about which countries suffer more or less from poverty? Yet the OECD does make such comparisons, year by year, as if it were telling us something important about actual poverty.

Approaches to “Eliminating Poverty”

In an online PDF file updated to August 2016, the OECD offers two distinct versions of child poverty. One is the “child income poverty rate,” defined as “the proportion of children (0-to-17 year olds) with an equivalised post-tax-and-transfer income of less than 50% of the national annual median equivalised post-tax-and-transfer income.” The other is the “poverty rates in households with children and a working-age head by type of household and household employment status.” The definition of the latter is long and intricate, but basically it boils down to 50% of a median reached by a comparison of families-having-children, instead of the direct comparison between individual children upon which the “child income poverty rate” is based. (The intricacies come from the need to group families by type according to the number of adults and the number in jobs.) Indignation over “the proportion of children living in families below the poverty line” refers to the second definition. The document in question goes on to note that in any specific country the one or the other definition may yield a higher figure for “child poverty.” Those differences, however, will not affect what we shall point out next.

Given either OECD definition of the “poverty line,” let us consider two theoretically possible approaches to eliminating poverty in Israel — or in any other OECD country. One approach is to raise everyone’s income in real terms by one hundred times. You would think that this enormous effort would lift even families on the lowest incomes out of poverty. But no, because the OECD’s officially defined poverty line, too, would have automatically and simultaneously risen one hundred times. Everyone is allegedly just as poor as before.

The second theoretically possible approach is to lower everyone’s income to the point that one half of Israeli children (first definition) or Israeli households by type (second definition) have an income of 1.01 shekels a year and the other half have 0.99 shekels a year. You would think that this would plunge everyone into utter poverty. But no: according to the OECD definition there is now no poverty at all because the median child/household income is one shekel a year and no child/household falls below 50% of that.

According to either OECD definition of the “poverty line,” therefore, you can make everyone fabulously rich while keeping them all as poor as before. But you can eliminate poverty by reducing them all to starvation levels.

What particularly agitates readers of OECD poverty reports, as we noted, are statements about “the proportion of children living in families below the poverty line.” That is, reports based on the OECD’s second measure of child poverty. Also in this regard, various alternative approaches can be envisaged.

The usual approach is to tax the rich in order to provide children’s allowances that benefit children in poor families. This may be the moral thing to do and it may bring greater happiness to many poor children. Only it may also do nothing to reduce the number of children under the thus-defined poverty line. What if it encourages the poor to have more children while discouraging the rich from doing that? Then, in both regards, the number of children under the poverty line will increase. If the aim is to reduce that number, it may possibly be achieved by doing the opposite: taxing the poor to the point that they are scared of having children in the first place, and giving the money raised to the rich, enabling them to afford more children.

Indeed, given the second OECD measure of poverty, the one that compares families-with-children, there is even a sure and foolproof way of totally eliminating poverty in OECD terms. It is to confiscate all the children of the poor and oblige the rich to adopt them all. Once all children have been placed by an authoritarian government in households above the median household income by type of family, not a single child will live in a household falling under the poverty line. Even so, there may still be many children in actual poverty. This is because parents that were comfortably off while they had just one or two children may be financially challenged when they are saddled with more. The OECD will report that the phenomenon of children living in poverty has vanished, but in reality it is still there and has merely been made officially invisible.

That paradox arises with the OECD’s second definition. Whether a similar paradox infects the first definition, we leave as an exercise for the inquisitive reader.

Interestingly, Israel’s child benefits policy was changed in 2003 such as to mildly disincentivize ever-increasing families. For children who were born up to May 31, 2003: 150 shekels are granted monthly for the first child, 188 each for the second and third, 336 for the fourth and 354 each for any further child. For children who were born on June 1, 2003 or later: 150 for the first child and for the fourth and any subsequent child, but 188 each for the second and third. In the meantime, the proportion of children living under the OECD-type poverty line has decreased somewhat, such as in 2012 and in 2015. This gives Israel a somewhat improved grade from the OECD. In real terms, on the other hand, there is less government money available for all children and especially for large families, so actual poverty has presumably risen. Whether it has truly risen, however, can only be guessed; reliable figures for real poverty can hardly be found, as precisely that is not being measured.

This brings us back to the Wikipedia article mentioned earlier, which goes on to state:

“The United States, in contrast, uses an absolute poverty measure. The U.S. poverty line was created in 1963–64 and was based on the dollar costs of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s ‘economy food plan’ multiplied by a factor of three. The multiplier was based on research showing that food costs then accounted for about one-third of money income.”

This definition is obviously free of the paradoxes that afflict the OECD definitions. So why has the OECD not adapted the U.S. definition to its own case? The answer is that, given some basic national statistics from the population registry and the income tax authorities, the relevant OECD officials can very quickly calculate the figures that result from its definitions of the poverty line. Never mind that the figures may tell us nothing useful about poverty! The U.S. definition, which does yield useful information, requires much harder work to implement.

Even the U.S. definition may be inadequate in the meantime. The Wikipedia article adds that the “one-time calculation” of 1963-64 “has since been annually updated for inflation.” So has it not been updated to reflect the possibility that today food costs may no longer “account for about one-third of money income”? That is, even a realistic definition of poverty may require constant fresh hard work on its revision. That hard work, too, is evaded by the OECD definitions.

Inter-Country Comparisons

The OECD website offers another PDF file entitled “Five Family Facts,” which gives five statistics for all OECD countries in 2009, including Israel. Thus the file seems to have been compiled immediately after Israel joined in 2010. That is a few years ago, but the file remains useful as an example of the OECD approach. A link to the file on an OECD webpage lists it under “Press material and country notes.” This makes it the kind of OECD document that promotes alarming headlines in the press about alleged child poverty.

One of those five facts is variously called the “child poverty rate” (presumably the “child income poverty rate” mentioned above) or the “percentage of children living in poverty.” As we have seen, to paraphrase the former phrase as the latter phrase is slipshod and misleading. The “child income poverty rate” is a relative measure used by the OECD, whereas the “percentage of children living in poverty” is an absolute measure that the U.S. approach attempts to calculate. The second phrase, therefore, is out of place in an OECD document.

Under “Israel,” we are told: “In Israel, 26.6% of children live in poverty, which is the highest rate of the OECD and more than twice the average of 12.7%.” Several other countries, however, are rated not much lower, such as Chile (20.5%), Mexico (25.8%), Poland (21.5%) and Turkey (24.6%),

But Israel is absolutely in a class on its own in another respect: “The fertility rate in Israel is the highest in the OECD with 2.96 children per women, compared to an OECD average of 1.74.” The next highest, far behind, is Iceland (2.2). As for the other four countries just mentioned, the rates are Chile (2.0), Mexico (2.08), Poland (1.4) and Turkey (2.12). That is, Israeli women are having some 50% more children than women in three of those countries and over 100% more than women in Poland, yet Israel’s so-called child poverty rate is by no means so much greater. This puts the alleged child poverty in Israel in a very different light: Israel seems to be performing better than those four countries

Add to this the fact that the OECD document repeatedly notes that a fertility rate of 2.1 is required to maintain a constant population. Apart from Israel and Turkey, only Iceland (2.2) and New Zealand (2.14) achieve this. Another eight countries have a rate of 1.9 or more: Australia (1.9), Chile (2.0), Ireland (2.07), Mexico (2.08), Norway (1.98), Sweden (1.94), the UK (1.94) and the USA (“just over 2”). Since the three Nordic countries all have child poverty rates under 10%, they would seem to outperform all the others. On the other hand, Israel might be seen as also doing better than countries like Spain, which has a child poverty rate of 17.3% despite a fertility rate of only 1.4.

In the previous section, we pointed out that OECD figures about “child poverty” may have little to do with actual poverty. The approach in this section was: Assume that large differences between OECD countries in alleged “child poverty” may, nevertheless, have some significance. The consequence of this assumption, however, is that Israel is doing better than numerous other OECD countries when the uniquely high fertility rate in Israel is taken into account.

OECD figures about “child poverty” may have little to do with actual poverty. But even assuming that large differences between OECD countries in alleged “child poverty” may, nevertheless, have some significance, it means that Israel is doing better than numerous other OECD countries when the uniquely high fertility rate in Israel is taken into account. OECD figures about “child poverty” may have little to do with actual poverty. But even assuming that large differences between OECD countries in alleged “child poverty” may, nevertheless, have some significance, it means that Israel is doing better than numerous other OECD countries when the uniquely high fertility rate in Israel is taken into account. |

Annual Ritual

Every December, Israel’s National Insurance Institute issues its own “poverty report” for the previous year (thus in December 2016 for the year 2015), based on OECD-type definitions. The immediate response is a great hoo-ha for a day or two. Even if poverty is said to have fallen slightly, the remaining allegedly high levels of poverty are noisily deplored. Opposition politicians castigate the government, which responds by alleging that the opposition did even worse when it was in power. General consensus: we must do better. After that day or two, however, the matter is forgotten and the media revert to other current controversies.

Realizing that its annual poverty reports have no lasting impact, the National Insurance Institute resorted to issuing reports twice a year instead. The result is merely that the phenomenon of instant uproar followed by instant apathy now occurs twice as often. We do not know whether the economic wise men in government ministries understand what we wrote above, but treat it as esoteric knowledge to be kept secret, or whether they are simply frustrated by years of vain attempts to produce a major change in the official figures.

In fact, the National Insurance Institute does much excellent work on researching actual poverty and on devising means to help poor families. Israel has also developed effective programs for bringing people back into work. When Binyamin Netanyahu — then as Finance Minister — changed child benefits in 2003, for instance, he also made changes aimed at encouraging single mothers to enter the labor market. The result up to mid-2016, we are told, was that “the proportion of single mothers who work has risen by about 15 percentage points – but the proportion of single-parent families below the poverty line has remained unchanged.” That is: “In 2015, 81 percent of single mothers worked. But just as in 2002, a quarter of them were poor.” Here again, we see that “below the poverty line” is misleadingly equated with “poor.”

It was a real achievement to raise the employment rate of single mothers from 66% to 81% between 2002 and 2015. To insist that nothing has changed because the same proportion of such families remains below the so-called poverty line is both wrongheaded and could discourage attempts to improve the situation further.

According to OECD figures for late 2016, Israel’s unemployment rate at 4.7% was comfortably below the OECD average of 6.3% and well below the European Union average of 8.5% and the Euro area’s average of 10.0%. Only six OECD countries had lower rates. In the meantime, Israel’s rate fell to 4.3% at year-end 2016.

For people in general, just to be in work instead of out of work is beneficial even on the same household income level. On the one hand, they are contributing to their society instead of living off it. On the other, being in work encourages self-esteem, multiplies social contacts, and makes the individual concerned more attractive to a future employer offering higher wages than members of the longtime unemployed.

It is sometimes thought to be paradoxical that Israel features so highly in the “World Happiness Reports” — at 11th place out of 157 countries, in the latest report. (Preceded only by the five Nordic countries, the three Commonwealth Dominions, Switzerland and the Netherlands.) There is no paradox if such factors as joy over having children and pride at being in work outweigh artificially defined poverty.

Malcolm Lowe is a Welsh scholar specialized in Greek Philosophy, the New Testament and Christian-Jewish Relations. He has been familiar with Israeli reality since 1970.

Comments are closed.