By Joshua Lawson:75 Years Later, It’s Clear Truman Was Right To Drop The Atomic Bomb

On August 6, 1945, 30-year-old U.S. Air Force pilot Col. Paul W. Tibbets Jr. took to the sky in the Enola Gay, his Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber. His destination, the Japanese city of Hiroshima, was not an especially notable target. His payload, however, a single bomb nicknamed “Little Boy,” would change the course of history.

True watershed moments in history are rare — the agricultural revolution is one such example, as was the Battle of Salamis, the advent of Jesus Christ, and the fall of Western Rome. Yet in the last 1,500 years, no two distinct epochs of time are as clear as the time before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and all the time since.

‘Prompt and Utter Destruction’

Eleven days before Tibbets’s fateful flight, on July 26, 1945, U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s “Potsdam Declaration” gave the Empire of Japan one final chance to surrender unconditionally after more than three years of war in the Pacific. If they persisted in fighting, the Potsdam text promised “the full application” of U.S. military power, culminating in “the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland.” The closing of the ultimatum rings all the more forebodingly in hindsight: if the Japanese refused the terms, the alternative was “prompt and utter destruction.”

In his 1947 memoir “Speaking Frankly,” Truman’s Secretary of State James F. Byrnes observed the Potsdam warning was “phrased so that the threat of utter destruction if Japan resisted was offset with the hope of a just, though stern, peace if she surrendered.” Yet, on July 28, Japan Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki proclaimed the offered terms “unworthy of public notice” With that, the die was cast. Truman gave the final go-ahead to drop the atomic bomb on his way home from Potsdam.

The uranium bomb carried by the Enola Gay exploded over Hiroshima with the might of 15,000 tons of TNT. On August 9, “Fat Man,” a plutonium device of even greater explosive power, was dropped on Nagasaki. The desolation wrought by the blasts was unimaginable. Including the effects caused by radiation, estimates for the number of mortalities range from around 110,000 to a high of 210,000.

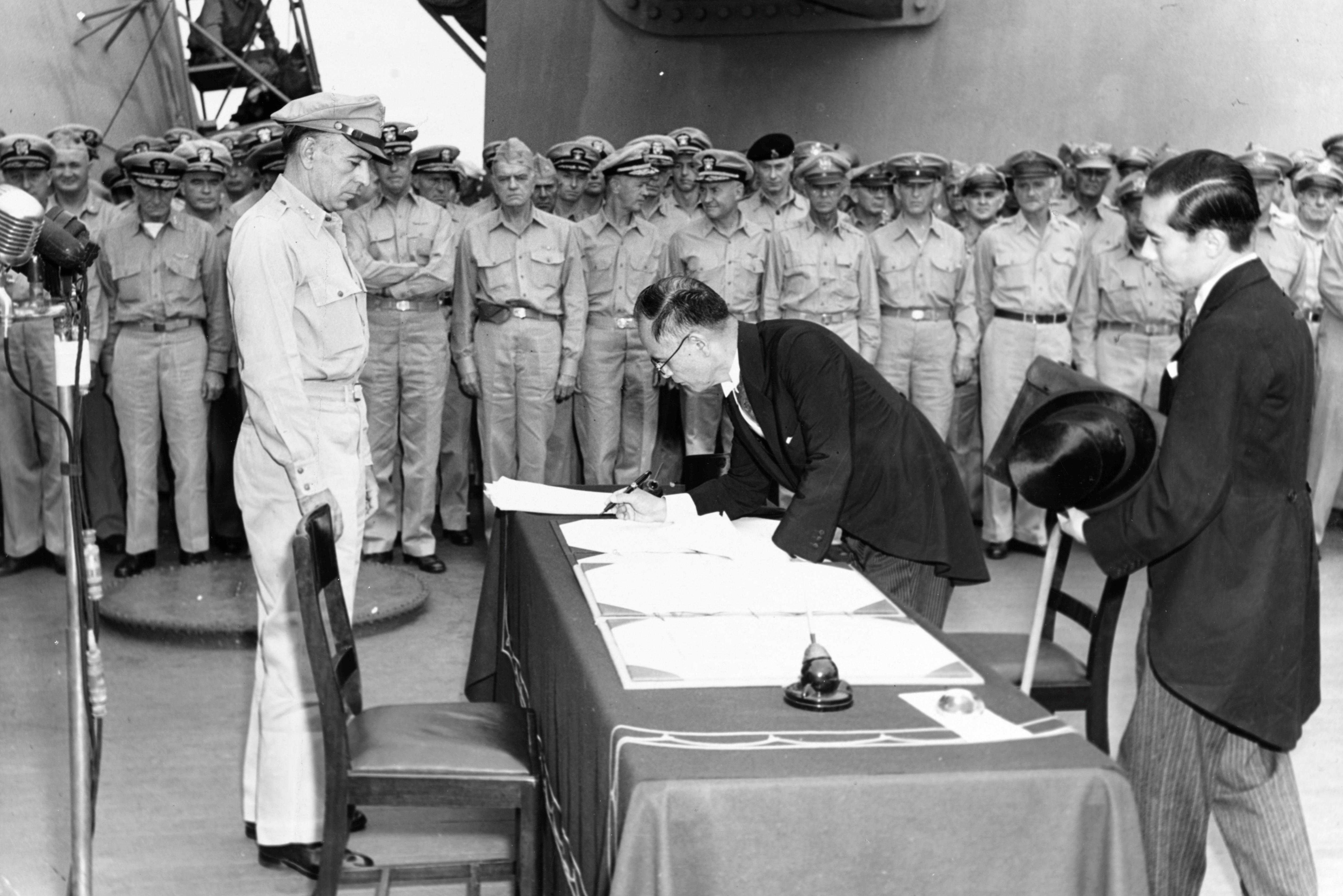

Utterly shaken by the display, within one day, the Japanese agreed to a conditional surrender, a stance that was rejected, as promised, by the United States. By August 14, however, the Japanese agreed to accept the Potsdam Declaration without any conditions. Formal surrender took place on September 2, onboard the USS Missouri.

From almost the moment the war ended, critics began to assail the atomic act, claiming the bombings were uniquely immoral and unnecessary. Yet today, viewed from 75 years of accumulated data and insight, Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb can be viewed with better context.

Ultimately, the decision played an indispensable role in shocking and unmooring the resolve of Japan’s militaristic regime into unconditional surrender and hastening the end of the Second World War. Furthermore, intended or not, the decision deterred short-term Soviet aggression, sparing much of Eastern Europe and parts of Asia from brutal Soviet domination.

Most importantly, Truman’s fateful choice saved millions of American and Japanese lives. It was the correct and justified decision 75 years ago, and it remains so today.

‘A Psychological Weapon’

In his testimony to the U.S. Senate on May 11, 1951, Gen. George C. Marshall conveyed the terrible challenge facing the U.S military in 1945:

It was evident to us that the Japanese army was still largely in control and they were preparing to fight to the bitter end just as they had done on all of the islands up to and including Okinawa. … Therefore, it was the opinion of the Cheifs of Staff … that nothing less than a terrific shock would produce a surrender. … Our great struggle there was to precipitate that general surrender so that we would not be involved with various hold-out commands in various parts of the Far East. Therefore, our own conclusion, that of the Chiefs of Staff, was that we had to either invade Japan or bring this to a conclusion with shock action … the atomic bomb.

The central conundrum facing the U.S.-led Allied leadership was how to coerce an utterly indefatigable and stubborn Imperial Japan to surrender without caveats or conditions. After three years of intense fighting, the war had to end — the sooner the better. The heavy toll of the conflict weighed increasingly on the United States in financial, and more importantly, human treasure.

Non-atomic options for bringing the war to a speedy conclusion raised more doubts then they dispelled. The prevalent doubt amongst U.S. Army leadership that the Japanese would quickly and suddenly back down in the face of conventional attacks or a blockade wasn’t just grounded on the last three years of fighting its zealous combatants — it found historical parallels within living memory.

“Had not their military histories taught them that the hopelessly beaten Confederate Army had battled?” notes historian Herbert Feis, “Had they not witnessed the refusal of the Germans under the fanatic Hitler to give up long after any chance of winning was gone?” Indeed, since 1942, Japanese devotion to the war had developed a fanatical, quasi-religious overtone, and it was doubted by no one who had encountered the Empire’s troops in battle.

The question of a blockade met understandable apprehension. The specter of Japanese planes killing tens of thousands of American sailors in kamikaze attacks was very real. Since the suicide strikes began, Japanese pilots sunk 34 ships — including three aircraft carriers — and damaged another 285, including 16 sunk ships and another 185 damaged in the Okinawa campaign alone.

Furthermore, a protracted blockade would have taken a while to hurt the well-connected, well-fed Japanese military establishment. Millions of the Empire’s average citizens would have to suffer a slow and agonizing death from starvation.

Strategic bombing of Japanese cities was another option, but it had been attempted previously to little diplomatic effect despite the death toll. By August of 1945, nearly all Japanese cities with populations over 40,000 had already been devastated by conventional bombing raids.

Aside from sacrosanct cultural locations like Kyoto or the half-dozen cities “saved” for possible atomic bombings, meaningful future targets were in short supply. Marshall later lamented the horrific firebombing of Tokyo seemingly “had no effect whatsoever” on Japanese morale or towards hastening the Empire’s surrender, despite killing as many as 200,000 civilians.

For those with close knowledge of the top-secret Manhattan Project charged with building the world’s first atomic bomb, there was little debate or doubt that once the bomb was successfully built, it would be used. The only question was “when?”

The atomic bomb was the key to shaking the legendary resolve of Imperial Japan. Yet to have the desired result of hastening the war, the bomb would have to be deployed in combat — options involving other ways of “using” the device were considered but dropped upon further consideration of the risks involved.

On June 16, 1945, the U.S. Secretary of War’s advisory Scientific Panel, whose membership featured Enrico Fermi and J.R. Oppenheimer, concluded in their report:

We can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.

Writing 15 years after the bombs were dropped, award-winning historian Samuel Eliot Morrison reported a proposal to demonstrate the power of the bomb by detonating it over a relatively uninhabited part of Japan was rejected for two main reasons. For one, there was a credible fear that, after the requisite fair warning, Japan would move allied prisoners of war into the expected blast zone.

More importantly, no one was certain the bomb would work. If, after a grandiose promise of technological power, the bomb was a dud, the United States would find itself, as Morrison put it, “in a ridiculous position” and Japan would have only been emboldened to resist longer and with greater ferocity.

As Truman’s Secretary of War Henry Stimson later pointed out, “the atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon.” Dr. Karl Taylor Compton, former president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and member of Truman’s select Interim Committee, later agreed:

It was not one atomic bomb, or two, which brought surrender; it was experience of what an atomic bomb will actually do to a community, plus the dread of many more, that was effective.

Nearly a year before the end of World War II, in a September 18 speech before the American Legion, Marshall remarked, “War is the most terrible tragedy of the human race and it should not be prolonged an hour longer than is absolutely necessary.” Given how deadly the Pacific theater had become, something had to be done to stop the war and bring peace as soon as possible. The atomic bomb was ideally suited for this task.

Stalling the Red Menace

In his 1914 novel “The World Set Free,” H.G. Wells predicted atomic-based weaponry 19 years before Leó Szilárd formulated the concept of neutron chain reaction. The power of the new bombs, Wells foretold, would be the final convincing argument for the awful nature of war — but not before “the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands.”

A memorandum written by Stimson and shared with Truman on April 25, 1945, turned out to be highly prescient. “If the proper use of this weapon could be solved,” wrote Stimson, “we would have the opportunity to bring the world into a pattern in which the peace of the world and our civilization can be saved.”

Indeed, the use of the bombs had the crucial effect of demonstrating American military might. The show of force sufficiently prevented the Soviets from completely overrunning the Far East and changed their probable course of action in both Central and Eastern Europe. Ending the war with Japan as quickly as possible would prevent the chance for Soviet-Japanese fighting to become a guise for seizing land throughout Asia with no intention of relinquishing conquered lands in the future.

Nobel-prize winner P.M.S. Blankett argues “the dropping of the atomic bombs was not so much the last military act of the Second World War, as the first major operation in the cold diplomatic war with Russia.” Even historian Gal Alperovitz, a staunch opponent of the decision to use nuclear weapons on Japan, admits that had the United States not dropped the atomic bombs the Soviet Red Army might not have left Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Iran, or Manchuria.

Furthermore, a convincing case can be made that dropping the atomic bombs on Japan helped ensure a Third World War never occurs. In a 1965 essay, Richard Rovere, a columnist for The New Yorker, wrote, “if we had spared Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we would have been all the more tempted to use it [the atomic bomb] on Moscow and Leningrad a couple of years later.”

Had the full, catastrophic power of atomic weaponry remained unknown until the outbreak of a global East versus West conflict, it would have been too late to prevent nuclear Armageddon. Instead, in our timeline, the Great Powers of the world are so well aware of the terrible possibilities of such technology that even in times of overwhelming tension, would-be antagonists have thus far recoiled at their use in war.

Both Atomic and Strategic Bombing Proved War Is Hell

As determined by a joint Manhattan Project-U.S. Air Force targeting committee, targets for atomic bombing had to be primarily military in nature, yet also contain a large enough urban area, relatively untouched by previous U.S. Air Force bombings, to allow for the damage required to “shock” Japanese leadership into surrender.

Hiroshima was the home to a large shipyard as well as Field Marshal Shunroku Hata’s headquarters for the Second General Army. Originally added as a “finalist” target by Gen. Curtis LeMay’s staff as a “bad weather” alternative to Kokura, the city of Nagasaki represented a near-perfect target for an atomic attack with a high chance of cowing Japan to cease resistance. The prized electric and ordnance factories of Mitsubishi arms produced more than 96 percent of all weapons production by plants with more than 50 workers; its active dockyards provided additional high-value targets.

Beginning with the wider availability of bomber aircraft in the 1930s and certainly, by the 1940s, bombing military targets within cities was allowed and approved within the rules of war. Civilians killed in such aerial raids were considered “collateral damage.” In truth, the socio-political reality of 1945 might as well have been in a different universe compared to the limited professional armies that took to open fields in the 18th century in ordered lines and brightly colored uniforms.

By World War II, generals and politicians alike were attempting to come to grips with the fact that the line between a combatant and a non-combatant, while still visible, had faded considerably. As the size of armies grew from thousands to the hundreds of thousands and even millions, vast portions of society became necessarily involved with “feeding” such enterprises.

The destruction or incapacitation of plants involved in the manufacturing of weapons, munitions, or even uniforms meant depriving the enemy of war materials that could later be used to kill one’s troops tomorrow, next week, or next month. If one side disabled the gears of war, factories could not produce the means to enable a nation to continue fighting, wars could be shortened, and more lives would be saved in the end.

Strategic bombing was born out of this theorizing, and its gruesome harvest was arguably as horrible, or worse, as the ruination left in the wake of the dropping of the atomic bombs. While the radioactive, psychological, and single-burst effects felt at Hiroshima and Nagasaki may have been unique in the type of terror induced by atomic weapons, the death and injury caused by them was sadly in line with the carnage caused by conventional bombing raids in the final two and half years of World War II.

Some 22,700 to 25,000 German civilians died as a result of British-American bombing raids on Dresden between February 13-15, 1945. A little more than a week later, a British Royal Air Force bombing raid over the southwestern German town of Pforzheim killed 17,600 — nearly a third of its population.

Allied bombing raids of the German cities of Kassel (October 22–23, 1943) and Darmstadt (September 11-12, 1944) killed at least 10,000 and 11,500 civilians, respectively. The joint British-American bombing of Hamburg, Germany during the last week of July in 1943 killed an astounding 42,600.

Professor Donald J. Miller, one of the most trusted authorities on World War II, believes “at least” 100,000 civilians were killed in the Tokyo firebombing raids from March 9-10. Other more recent estimates believe between 75,000 and 200,000 civilians perished during the resulting conflagration. The minimum of 105,000 Japanese who died from the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is not a testimony to the unique horrors of the attacks, but to the inescapable and undeniable horror of war itself — especially in the 20th century.

‘Operation Downfall’

Of the nearly 1,250,000 combat and combat-related casualties the United States sustained in World War II, nearly 1 million were incurred between June 1944 to June 1945. The difficulty of the combat on Japanese islands, combined with the ferocity and tenacity of Imperial Japan’s fighting forces, brought the war in the Pacific to an entirely different level of danger. The ratio of enemy to U.S. casualties reached horrifying, intolerable numbers. Bitter fighting on Okinawa led to a ratio of 2 to 1; an even ghastlier ratio of 1.25 to 1 occurred with the combat that concluded on Iwo Jima.

The severe casualties suffered at Okinawa and Iwo Jima demonstrated the steely determination of Japanese troops to resist surrender. A common fear pervaded U.S. military leadership and the Oval Office that invading the Home Islands would amount to “a string of Okinawas,” but with exponentially higher casualties.

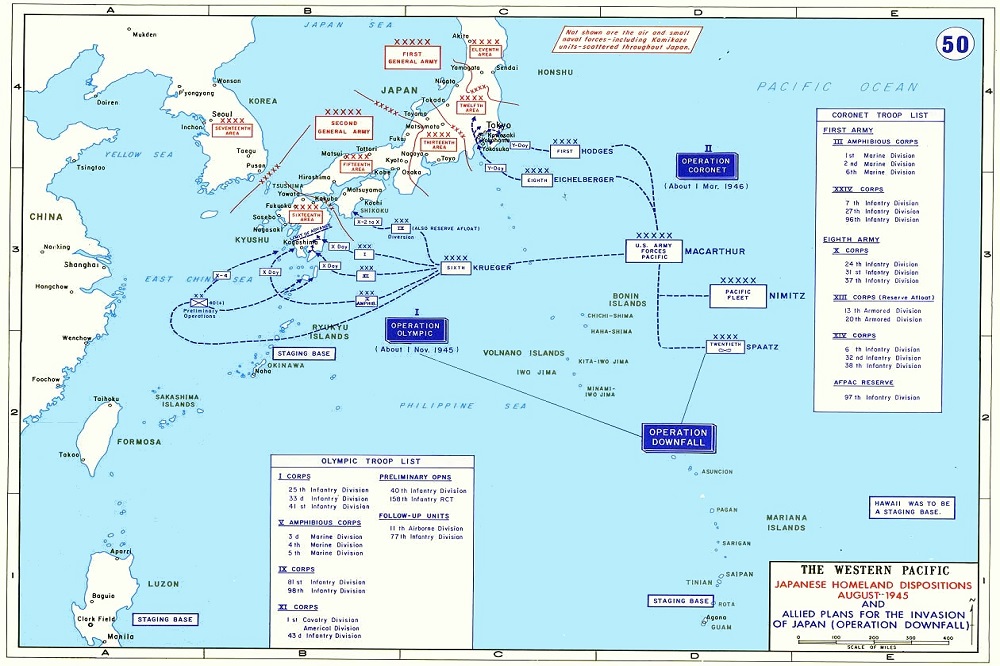

In a July 2, 1945, memo to the president, Stimson noted the terrain of the Home Islands was ideal for last-ditch defenses and even “more unfavorable to tank maneuvering than either the Philippines or Germany.” From the start of Operation Downfall, the planned ground invasion of Japan, 18 months was assumed to be the minimum amount of time needed to bring the war to a close barring “a sudden collapse.”

Chilling proof of the carnage expected to follow an amphibious invasion of Japan exists in the more than 495,000 Purple Heart medals made in anticipation of Operation Downfall’s casualties. While the plan scheduled for November 1, 1945, was never required, the amassed stock of medals was so vast that soldiers injured in the recent Afghanistan and Iraq wars received Purple Hearts from the very same stockpile meant for Japan in 1945. Even that harrowing number of Purple Hearts, however, still likely underestimated likely casualties from Operation Downfall.

‘Operation Downfall,’ the planned invasion of Japan.

Independently, Los Angeles Times war correspondent Kyle Palmer and former U.S. President Herbert Hoover both came to the conclusion that the nation should brace for a minimum of 500,000 dead Americans, with as many as 1,000,000 dying, to force the Japanese to surrender by conventional means.

The U.S. Army’s “Summary of Redeployment Forecast” issued on March 14, 1945, anticipated they would need “approximately” 720,000 replacements needed for all of the expected “dead and evacuated wounded” through December 31, 1946 — although this figure was only for U.S. Army and Air Force servicemen and did not include expected losses incurred by the U.S. Navy and the Marines.

“JCS 924,” the Joint Planning Staff’s finalized blueprint for the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands, warned taking the islands “might cost us half a million American lives and many times that number wounded.” By the summer of 1945, the number passed around B-29 training bases, the Pentagon, and U.S. First Army Headquarters in Weimar, Germany was a “best-case scenario” of 500,000 dead American soldiers.

Dropping the Atomic Bombs Saved Millions of Lives

Make no mistake, however: had the war continued into late August and beyond, no one would have suffered more than the Japanese people. Most ominous of all was the conclusion of a report compiled by Pentagon planners in July 1945. In addition to the report’s projected 400,000 to 800,000 American dead and 1.7 to 4 million casualties was that at least 5 to 10 million Japanese citizens and soldiers would be killed.

Before they saw the destructive power of American atomic weaponry, leading figures within Imperial Japan’s military leadership — including Vice Chief of the Naval General Staff Onishi Tikijiro and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Umeza Yoshijiro — privately considered “sacrificing” 20 million Japanese civilians in defense of the Home Islands. Fortunately for millions of Japanese and Americans, the terrible scenario of Operation Downfall never happened.

On August 15, over radio airwaves, citizens of Japan heard the voice of their hallowed emperor for the first time. In a pre-recorded transmission later known as the “Jewel Voice Broadcast,” Japanese Emperor Hirohito read out loud the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the Greater East Asia War. Without using the word “surrender,” Hirohito announced the end of Japan’s resistance after witnessing America’s “new and cruel bomb,” which, he proclaimed threatened not only the “ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation” but also “the destruction of all human civilization.”

Within the harsh confines of wartime, perfectly noble options exist only in the realm of fantasy. War typically offers awful alternatives and tragic trade-offs that, sadly, often require weighing the most precious thing on earth: human lives. The final major events of World War II remind us that in global conflicts, obvious decisions are few, bloodless victories are rare, and wars must be waged to secure peace as quickly as possible.

A near-impossible decision faced President Harry S. Truman in the summer of 1945. To his credit, and to the salvation of millions, his fateful choice was the right one.

Comments are closed.