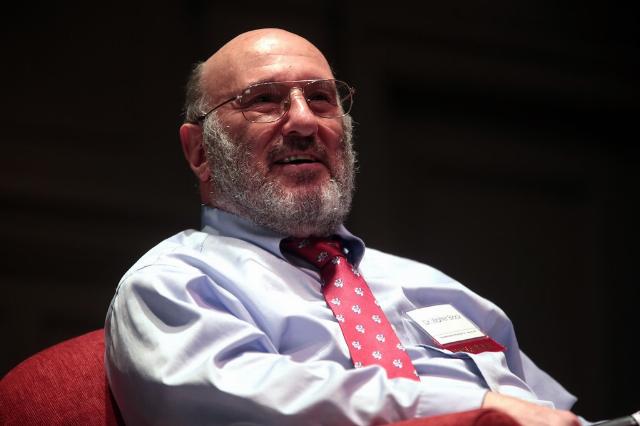

The Challenges of Utopian Thought in a Complex World By Allen Gindler

The phenomenon of children inventing imaginary friends is a well-documented and common occurrence in early childhood development. These imaginary companions are often endowed with idealized features, representing perfection in both character and behavior, and serve as companions in a fantasy world. However, as children grow and begin to form relationships with real peers, this phase of imaginary play typically fades.

In contrast to children, adults do not fabricate imaginary friends, but they do engage in the construction of grand ideals on a much larger scale. Rather than ideal companions, adults often imagine ideal societies — utopias in which human existence is perfected, and harmony with nature and fellow human beings is absolute. These utopian visions have historically shaped political and social ideologies. For instance, Karl Marx, while critiquing the utopian socialists for their collectivist fantasies, proposed a “scientific” theory for the construction of a communist society. In Marx’s vision, at the highest stage of communism, society would be free of class distinctions, inequality, and the state itself. Private property, conflicts, wars, and even the economic systems of commodity-money relations would cease to exist, and work would be driven by the common good, with individuals receiving according to their needs.

However, this utopian vision was not without its stipulations. To achieve such an ideal society, Marx advocated for the world dictatorship of the proletariat, a transitional phase in which the working class would mold the unconscious masses into a new kind of human being — one so ideal that it is reminiscent of Plato’s conception of ideal forms.

The new human being in Marx’s utopia would embody an ideal, perfect in nature, harmony, and cooperation. Yet, history has shown that those who resisted this transformation were quickly “crossed off the lists,” metaphorically and often literally, as the march toward communism pressed on. The tragic consequences of this pursuit were felt most acutely in the Soviet Union, where ordinary citizens, caught in the throes of communist ideology, cynically referred to their political and ideological leaders as “Kremlin dreamers.”

Nonetheless, the impulse to imagine and construct ideal forms is not confined to left-wing ideologies. On the right side of the political spectrum, anarcho-capitalists also envision an ideal society — albeit one rooted in fundamentally different principles. In the anarcho-capitalist ideal, the state has no place. All property is privately owned, including what are typically seen as public goods, such as roads, police forces, and military services. In this vision, society functions entirely through voluntary exchange, where individuals produce, trade, and compete in a free market. Conflict is minimized, proponents argue, through adherence to the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP), which ensures peaceful cooperation.

Despite its theoretical coherence, this ideal society has never existed in practice, and it remains uncertain how it would function in reality. Nonetheless, many find the concept of anarcho-capitalism extremely appealing, and even argue that anarcho-capitalism presents an ideal worth striving for.

Yet, this vision too encounters a fundamental obstacle: human nature. For anarcho-capitalism to succeed, it also requires a “new” kind of human being, one who fully respects the property of others, tolerates differing values and beliefs, and adheres strictly to the NAP. Moreover, those who own and serve in private police forces or armies must behave like noble knights, not exploiting their power for personal gain. Likewise, community leaders must refrain from using their influence for self-interest.

The theory of anarcho-capitalism is, of course, a fascinating intellectual exercise, but the evolution of human beings is not even close to that ideal. However, many theorists of anarcho-capitalism have chosen the convenient policy of criticizing everything and everyone from the height of their ideal. First of all, the state gets “the brunt,” especially because of its two actions: intervention in the economy and military aggression.

The theory of anarcho-capitalism is, of course, a fascinating intellectual exercise, but the evolution of human beings is not even close to that ideal. However, many theorists of anarcho-capitalism have chosen the convenient policy of criticizing everything and everyone from the height of their ideal. First of all, the state gets “the brunt,” especially because of its two actions: intervention in the economy and military aggression.

One cannot but agree with their criticism in principle. Any rational libertarian understands all the negative consequences of state intervention in the economy, and there are no differences of opinion here among all the advocates of the market economy. However, there are annoying exceptions when the economy has to give in to political needs, such as the security of society.

When it comes to military aggression, the situation should be clear — the NAP provides a straightforward guide for how a society or state should behave in international relations. Libertarians are justified in criticizing their governments for engaging in aggressive, unjust wars, as well as conflicts with unclear goals or uncertain criteria for what constitutes victory. On the other hand, if a nation becomes a victim of aggression, it has the right to defend itself by all necessary means. In such cases, the NAP takes a back seat until peace is restored.

The situation becomes more complex when other nations are engaged in conflicts, and anarcho-capitalists remain bystanders. In these instances, their stance often involves criticizing their own government for offering military or financial aid to other countries. Regarding the warring nations themselves, opinions vary depending on personal sympathies and preferences. While anarcho-capitalists might first condemn the governments involved for violating the NAP, they do not always take the time to determine which side is the aggressor and which is the victim.

For example, consider the Israeli/Hamas and Hezb’allah conflict and the response from the Mises Institute think tank. A review of their recent opinions reveals a failure to clearly distinguish between right and wrong and an inability to identify where injustice lies. The articles of some authors are written in a new genre that blends anarcho-capitalist rhetoric with the typical grievances of latent anti-Semites and self-hating Jews. These contributors, with the complicity of editors, apply double standards to Israel and falsely accuse it of crimes it did not commit, including genocide.

The Mises Institute not only suppresses differing viewpoints on the issue but has also carried out purges reminiscent of Stalin, dismissing world-renowned scholar Walter Block, a foundational figure in libertarian theory, for his support of Israel. Professor Block, also an anarcho-capitalist, identified the origins of the long-term conflict in the Promised Land and recognized the exceptional role of the Jewish state in safeguarding both its citizens and the global Jewry. He outlined these views in his book The Classical Liberal Case for Israel, co-authored with Alan Futerman, as well as in numerous articles on the subject.

At its lowest point, some even called for Professor Block to no longer be considered a libertarian, while others suggested that, although he may grasp the micro issues of libertarianism, he errs on global matters. However, it is rather absurd for mediocrity to dismiss a brilliant thinker, and even more ridiculous to attempt to exile him from a philosophical movement, as if they hold ownership over it.

Ironically, Ludwig von Mises, after whom the institute is named, was an ethnic Jew and a Holocaust survivor. If one were to consult AI on Ludwig von Mises’s likely stance on Israel’s conflict with Hamas and Hezbollah, it would align closely with Professor Block’s position.

The actions of the Mises Institute only reinforce the earlier point: humans are inherently imperfect, and neither left-wing nor right-wing ideologies can achieve an ideal society. An ideal form should not serve as a rigid blueprint for the complex realities of the world we inhabit. Instead, it is more important to first grasp the fundamental, universal concepts of good and evil before immersing oneself in abstract theories like communism or anarcho-capitalism. While children can be indulged in their play with imaginary friends, adults must exercise greater responsibility when applying utopian ideals to serious matters such as peace and war, survival and death.

Comments are closed.