EXCLUSIVE: A High Schooler Graduated with a 3.4 GPA. He Couldn’t Even Read.Frannie Block

Now, the Tennessee teen is suing his school district.

When William graduated high school in 2024 in Clarksville, Tennessee, he couldn’t read the words on his diploma. Despite ending the school year with a 3.4 GPA, he couldn’t even spell his own name.

That’s why William sued his school district, claiming it had left him “illiterate” and that he was denied the “free appropriate public education” guaranteed to all students by federal law.

On February 3, a federal appeals court sided with William, concluding that he was “capable of learning to read,” and agreeing with his claim that his lack of education had caused him “broad irreparable harm.”

William, whose last name is listed only as A. in the suit, first enrolled in the Clarksville-Montgomery County school district in 2016 when he was in the fifth grade. For the next seven years, he scored mostly in the bottom first, second, or third percentiles of his reading fluency assessment tests compared to national standards. In 2019 and 2020, he scored in the bottom ninth and sixth percentiles, respectively. But, a year before he graduated, his reading had regressed so much he was scoring below the first percentile.

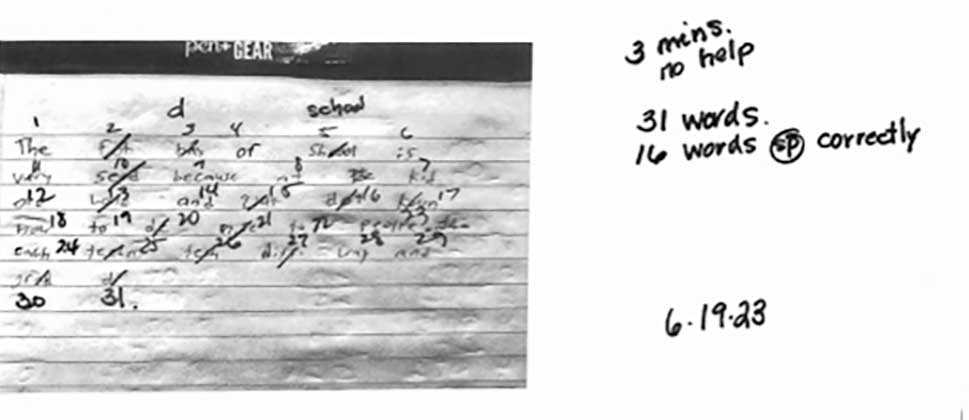

That same year, William took a simple writing test asking him to spell 31 words in three minutes. According to his suit, he couldn’t spell half of them, including the word school, which he wrote as shcool.

During all that time, William’s teachers were aware of the problem, but they did nothing to solve it, his suit says. In January 2020, when William was a freshman, a special education teacher asked the school psychologist, “Please take a look at William. I am very concerned. This kid can’t read,” according to the suit. But the school took no action, the suit says, other than giving him 24 hours to complete his assignments.

But even this “solution” was a problem. Because when William was at home with his schoolwork, he relied on AI programs like ChatGPT and Grammarly to complete his assignments for him, according to the judge who ruled on his suit last week. As a result, William continued to achieve high marks on his classwork throughout his entire four years of high school, even though teachers knew he was illiterate.

In November 2022, when he was a junior in high school, William’s parents paid an outside specialist at the Clarksville Center for Dyslexia and Learning Differences to assess their son. After he was diagnosed with dyslexia, they hired a private tutor to help him learn to read.

Soon after, the family decided to take legal action, filing their complaint with a local court in March 2023. It argued that the school district had violated their son’s due process rights by not providing him a proper education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which gives school districts federal dollars to teach disabled students.

In June 2023, a judge ruled in William’s favor, demanding that the school district provide him with 888 hours of “compensatory education.”

The school district appealed. But this month, three judges in a federal court of appeals upheld the decision. Justin Gilbert, one of the attorneys representing William, told me the ruling “illustrates that use of artificial intelligence is not a panacea, and certainly it’s no substitute for actually learning to read.”

“Reading is an issue of national importance,” he added. “And that includes the dyslexia community.”

Meanwhile, William’s family has launched a second suit in federal court, arguing that his school district violated the Americans with Disabilities Act as well as the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The suit also claims the school’s practice of “inflating grades and the graduation track artificially” served to boost the district’s “graduation statistics with the state,” at the expense of students like William.

As I recently reported for The Free Press, the trend for grade inflation is becoming a national problem for all students, with New York, Wisconsin, and Oklahoma recently lowering the “cut scores” on their tests so students appear to be performing better—even as national standardized tests show that American kids’ proficiency in reading and math is at the lowest level in thirty years.

William’s lawsuit exposes how this phenomenon impacts some of our country’s most vulnerable students. As his second suit states, the district “has a pattern, policy, or practice of allowing students” with learning disabilities “to suffer with illiteracy.” This illiteracy “affects, and will continue to affect, William in profound and staggering ways relating to his engagement in public life—the right to vote, understand contracts and rights, find work, pay bills, read medication labels, secure housing, and participate in his own education.”

His case is set for a jury trial this August.

A spokesperson for Clarksville-Montgomery County Schools told The Free Press that the district “cannot comment on pending litigation” and is also unable to “discuss specifics of the allegations due to state and federal student privacy laws.” He referred The Free Press to the district’s grading and retention policies, which say middle school students cannot move on to the next grade level unless they show “successful completion” of three out of four subjects: language arts, math, science, and social studies.

Around 20 percent of the population—or one in five people—struggle with dyslexia in the U.S., but the job of America’s public education system is “to serve the children who are in our schools, regardless of what accommodations they may need,” said Chelsea Crawford, the executive director of education advocacy group TennesseeCAN and the former chief of staff at the Tennessee Department of Education.

“What we’re supposed to do in K–12 education—it’s not passing students on, it’s not awarding participation diplomas,” Crawford said. “It’s actually ensuring children are learning academic content that helps them be successful as adults.”

William’s case is a particular tragedy because, by the time he received private tutoring, he’d already missed out on the important formative early years of education, she said.

“There is a time when your body is primed to learn content, and that goes away as you get older,” Crawford said. “That’s why early literacy and early reading is so important, because your brain is forming your ability to access and utilize language in those early years. Your brain closes off that development over time.”

Jenine Hanson, who runs the advocacy group Dyslexia Action Group of Naperville, Illinois, says there is no excuse for not teaching students with the learning disability to read. “Schools are required by law to find these children and intervene,” Hanson said. “It’s a crime that this is not part of school.”

William is just one of two dyslexic students who attorneys Justin Gilbert and Jessica Salonus are representing against Clarksville-Montgomery County Schools. There is also the case of Matthew B., a student who sued the district claiming that for nine years, his needs for additional instructional support “were ignored.”

In April 2024, Matthew was awarded compensatory education for four years of weekly instruction totaling about $60,000. Matthew also has an equal opportunity suit similar to William’s that is pending in federal court and awaiting a jury trial.

“He was literally passed from grade to grade to grade to grade to grade to grade to grade to grade to grade—nine grades—without being taught to read with the appropriate instruction for his dyslexia,” his lawsuit states.

“Had Matthew actually been provided the necessary dyslexia interventions,” the suit says, “he would have been a functional reader by fourth grade. Instead, Matthew could not read at all.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated the amount of “compensatory education” one of the student’s received was around $15,000, when it was actually around $60,000. This has been updated. The Free Press regrets the error.

Comments are closed.