THE SAD EXILE OF MARTY PERETZ

Peretz in Exile

For decades, Martin Peretz taught at Harvard and presided over The New Republic�a fierce, if controversial, lion among American intellectuals and Zionists. Now, having been labeled a bigot, taunted at his alma mater, and stripped of his magazine, he has found peace in a place where there is little: Israel.

- By Benjamin Wallace-Wells

- Published Dec 26, 2010

|

|

(Photo: Christian Weber)

|

The part of Israel that remains perfect to Martin Peretz is vanishingly small. But it does still exist, tangibly enough that you could trace its perimeter on a map of Tel Aviv: the ethnically mixed neighborhoods of Jaffa, the impeccably preserved Bauhaus downtown, the symphony halls and dance theaters, the intersections that still hold traffic, tense and honking, at 2:30 in the morning, the cosmopolitan sidewalk cafés that make real the old liberal dream. Peretz, the longtime owner and editor-in-chief of The New Republic, has been living here since October, and he reported recently that he has seen performances by the progressive dance company Pilobolus, the Cape Town Opera, and a Malian jazz group, which drew �a very hip crowd.� The sections of Tel Aviv he inhabits are so secular, Peretz says with relish, that in his first six weeks he saw exactly �eleven guys with Orthodox clothes. That’s it.�

Peretz is a fervent believer in Israel, but he always found the country a little small and so has often kept his trips short. Now he is here for seven months, teaching English writing to a class of eight 15-year-olds�immigrants, many of them, and poor. Peretz’s curriculum begins with autobiography, a kind of first enrollment in the intellectual traditions of the West: Amos Oz, full of the fractious heat of family life, then Charles Darwin, circumspect, exacting. Peretz has been particularly taken with a young girl from Congo, who spoke of her homeland’s �undisciplined� tyranny. The word caught Peretz’s attention, and he asked her what she meant. A disciplined tyranny, she said, would never have permitted the rapes and the wanton violence. Her father, a Christian pastor, brought the family to the Holy Land, an escape to something better. �That was kind of touching,� Peretz says, adding wonderingly: �She has younger siblings whose first language is Hebrew.� Peretz has this capacity for awe. He saw in her a more modern Israel; he saw something to defend.

Peretz is a born belligerent. He was anti-Stalin by the age of 7; spent half a century defending a controversial brand of Zionism in the obscure, fratricidal fights of the ideological left; and retains a decisive eye for an enemy. Now, at 71, Peretz has a broad trunk and very narrow hips, and he leaves the impression of having been stuffed into his own skin, kicking and screaming. His extraordinary capacity for charm is matched by an extraordinary capacity for anger, only partly diminished by years of therapy. �His anger has always been so much a part of him,� says Anne Peretz, to whom he was married for 42 years, �that perhaps he doesn’t even realize he’s scaring people.�

The fight, for Peretz, has always been about Israel first, and it has become particularly wrenching recently. As the Palestinian Authority began its first halting steps toward modernization, Israeli politics and society have pivoted to the right. The country’s refusal to stop construction of new settlements; its growing hostility toward the international community and the Obama administration; its storming of an aid flotilla off the Gaza Strip in May�these postures and incidents have led some of the liberal intellectuals who have historically defended Israel to begin to edge away. This summer, Peter Beinart�once a protégé of Peretz’s�published an influential essay in The New York Review of Books arguing that liberalism and Zionism were becoming incompatible and noting that fewer and fewer secular, progressive American Jews feel a stake in Israel at all.

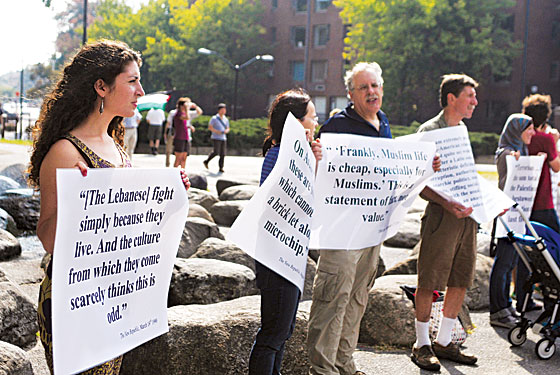

Throughout, Peretz has seemed to grow only more resolute, his constitutional truculence more evident. In September, writing on his New Republic blog The Spine, Peretz homed in on a familiar villain: Islamic terrorists who target other Muslims. �Frankly,� he wrote, �Muslim life is cheap, most notably to Muslims.� He got himself wound up: �I wonder whether I need honor these people and pretend that they are worthy of the privileges of the First Amendment, which I have in my gut the sense that they will abuse.� Nicholas Kristof began his Sunday New York Times column by denouncing the post; Peretz’s sentiments, he wrote, showed how �venomous and debased the discourse about Islam has become.� The Atlantic’s James Fallows, arguably the most reasonable man in liberal American letters, reviewed the evidence and concluded that Peretz is �broadly considered � a bigot.� Peretz had published many similar slanders in the past, but suddenly there were protests bent on a reckoning: a loud demonstration at Harvard, public letters demanding his condemnation, profound indignation across the left. The day after Kristof’s column, Peretz apologized for suggesting First Amendment privileges be revoked for Muslims. It was �a stupid sentence,� he now says. The rest he defended; it was what he believed.

|

|

Anne and Marty Peretz at The New Republic‘s 75th-anniversary party, 1989.

(Photo: Courtesy of Anne Peretz)

|

Peretz’s beef with the world is broad. �He is grumpy about modernity�there is an oldness about him,� says Fouad Ajami, the conservative Middle East scholar at the Hoover Institute at Stanford and a close friend of Peretz’s. The two have traveled together in the Middle East�Israel, yes, but also Egypt and Saudi Arabia�and Ajami says the Arab world, unexpectedly, suits Peretz. �Arabs understand Marty. He has that Middle Eastern quality: me against my brother, me and my brother against my cousin, me and my cousin against the world.�

Even Israel worries him now. �There are very many ways,� Peretz admits, �in which Israel is getting worse.� The early leaders of Israel, he says, were all kibbutzniks and ascetics; now he sees a gaudy oligarchy, with twenty business groups, many of them built from single families, that control a quarter of the country’s large companies. When he visits Jerusalem��a very poor city��he notices ultra-Orthodox boys running everywhere, and he disdains the sanctimony of the very religious and the �superpatriotism� of the Russian immigrants. And yet set against these growing groups is only a tiny liberal society. Peretz participates now and then in a vigil in the East Jerusalem neighborhood Sheikh Jarrah, in solidarity with Palestinians threatened with eviction. The demonstration has drawn great attention in Israel, but there are at best 120 people there, he says. �Take away my friends, and there would be 115.�

But Peretz isn’t just defending a state, with its flaws. He is defending an idea, of Israel and of himself. �Marty regards himself as a watchman,� says Leon Wieseltier, the longtime literary editor of The New Republic, �one of the people who stands on the wall and makes sure nobody who intends to harm what he loves is approaching.�

On Israel, the watchtower has become a very lonely place�TheAtlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg is on it with him, Peretz says, but there aren’t too many others. Even at The New Republic, there are only four people who Peretz believes really understand what is at stake in Israel: Franklin Foer, who has just departed as editor; Richard Just, who is now the magazine’s editor; Peretz; and Wieseltier. (�John Judis��another, more left-wing writer��knows zero.�) Among this small group, Peretz is closest to Wieseltier (�one of my two or three closest friends�), but he finds he no longer calls to talk to Wieseltier about Israel. �It always has to be more complicated with Leon,� Peretz says. �He always has to have this extra piece.�

There is an old Dwight Macdonald story about the fragmentation of the Trotskyist left in which�after many, many factional splits�the fate of the masses eventually rests in the hands of a lone married couple with a mimeograph machine: the Weisbords, heroes of the Passaic textile strike. Then, Macdonald writes, there was a divorce, and �the advance-guard of the revolution was concentrated like a bouillon cube in the person of Albert Weisbord, who sat for years at his secondhand desk � writing his party organ and cranking it out on the mimeograph machine.� Like Weisbord, Peretz is divorced. And in place of a mimeograph machine, he has a blog.

�My thesis adviser used to say to me, �You’re the last guard at Thermopylae,’ � Peretz tells me. He likes the image. �Although the last guard died, didn’t he?� He was slaughtered. Peretz thinks again. �So maybe I don’t like the comparison.�

Here is Marty Peretz in crisis. It is September 25, several weeks before he is scheduled to depart for Israel, and he has just parked his Prius at Harvard, on his way to a set of receptions that have been designed, in part, to honor him. It is the 50th anniversary of Harvard’s social-studies program, a radical’s redoubt where Peretz spent four decades, first as the program’s director and later as a lecturer. Peretz is fifteen minutes late to the ceremony, and he passes a crowd of about 25 protesters facing the lecture hall. He notices one sign in particular: MARTY PERETZ IS A RACIST RAT. But the protesters have their backs turned to him, and he manages to slide through unnoticed. He has that momentary, juvenile feeling of escape, of having gotten away with something.

The night before�a dinner in his honor at the Cambridge restaurant Harvest�had been spectacular. Peretz’s career had not been a conventional academic’s. Having married into wealth in his twenties, Peretz had never needed a professor’s paycheck, and he never had a scholar’s instinct for the esoteric. But he was a superb teacher, close to his students, and a mentor outside the classroom, too: He began lasting friendships with Al Gore, Yo-Yo Ma, James Cramer, and dozens of powerful lawyers and Wall Street types. His former students had endowed a research fund in his honor, with more than half a million dollars, and at the restaurant they all said the loveliest, most intimate things: how he had taught them what it meant to be a friend. How you could go a career without seeing someone inspire such affection. His children�Jesse, a filmmaker, and Evgenia, a writer for Vanity Fair�were at the dinner, too. This was Peretz as he wanted to be seen. �I’m a pretty vain guy, but it never occurred to me that my students were going to raise some money,� Peretz says. �I felt very touched.�

1974: Purchased by Peretz.

1977-1981: Michael Kinsley

1981-1985: Hendrik Hertzberg

1985-1989: Kinsley

1989-1991: Hertzberg

1991-1996: Andrew Sullivan

1996-1997: Michael Kelly

1997-1999: Charles Lane

1999-2006: Peter Beinart

2006: Peretz’s blog, The Spine, launches.

2006-2010: Franklin Foer

September 2010: Protests over Peretz at Harvard.

2010-2011: Richard Just

January 2011: Peretz steps down as editor-in-chief; The Spine is discontinued.

Photos: From Top, Vince Bucci/Getty Images; Patrick Mcmullan; Vince Bucci/Getty Images; Patrick Mcmullan; Peter Kramer/Getty Images For Tff; Kim Oster/Washington Post/Getty Images; Evan Agostini/Getty Images; Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images For Meet The Press; Brendan Smialowski/The New York Times/Redux; Sarah Claxton/Courtesy Of TNR

It had been just two weeks since Kristof’s column, and some of Peretz’s friends made passing reference to the controversy. But Peretz is famously generous�it is a quality as extreme as his partisanship. He has paid for medical treatments, found houses, coached careers. His close friend Michael Kinsley once told him, jokingly, that he should publish his collected letters of recommendation. Peretz has remained devoted to tarnished, even imprisoned friends, and he commands an outsize loyalty in return. Eleven years ago, at his 60th birthday, a blowout under the Brooklyn Bridge, the attendees included two guests who were submerged in separate arguments with Peretz so furious that neither had spoken to him in months, and each felt like just about killing him. And yet skipping the event seemed impossible. So they both came to New York, angrily nursing their respective grievances, prepared to sit amid the revelry for the party’s duration in furious silence, slowly realizing the terms of their allegiance.

But in Cambridge these loyalties were no longer enough to keep Peretz insulated; his long published record of provocations spoke for itself, and the social-studies alumni�many of them aging radicals�were angry. In the lecture hall that morning, Peretz found his old friend Michael Walzer, the left-wing political theorist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and longtime co-editor of Dissent. Something nasty seemed to be starting, Walzer said. His blog posts were being discussed from the stage. When it came time to go to lunch, Peretz and Walzer tried to leave via a side entrance, figuring they might escape the protesters outside a second time. No luck. There were 40 people now, and there were chants: �Harvard, Harvard, shame on you, honoring a racist fool!� Peretz looked waxy, distracted, unsure whether to laugh it off or attempt a sneer. He felt like a defendant leaving a courthouse; he worried he was embarrassing his friends. Peretz found himself wondering who these people were: not students, he thought, and not faculty. He settled on �the usual intellectual detritus that collects around the university.�

But some of them were students, and they held signs, each with a printed Peretz quote offering a sweeping ethnic generalization: �The stark fact is that the educated black middle- and upper-middle classes do not go to museums, and they do not go to concerts either.� �Terrorism � is about the sum total of what the Palestinians have bestowed on our civilization during the last five decades.� �Some of Marty’s friends were surprised that he would make those statements,� says Henry Rosovsky, a close friend of Peretz’s and the retired dean of Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. �I wasn’t, because I had been reading his blog.�

�I don’t know whether it was an instance of cruel justice or cruel injustice,� says Hendrik Hertzberg, a former New Republic editor. �It was certainly hugely sad.� Once Peretz had organized Vietnam War protests; now, says a friend, �he was McNamara.� He suffered through lunch, where he noticed a �murmuring all around� and listened to the keynote speaker implore the program not to take money from Peretz’s friends. He spoke only briefly and skipped the afternoon sessions altogether. As the child of immigrants, Peretz says, �Harvard was my Americanization. And so I got a little bit kicked in the groin.� The Harvard cops drove him home. Only later did he realize that he had left his car on campus, where it had collected a ticket.

When I met Peretz ten weeks later, he still seemed on edge. The bigotry charge was what lingered. �I mean, it hurts,� he said. We were in the dining room of the Loews Regency Hotel in midtown Manhattan, where the waiters greet him as �Dr. Peretz.� At a basic level, he said, he can’t be a bigot; he mentioned two close, personal black friends, one who is �so fucking smart,� and then a third, a black student whom he had plucked from Harvard and made the circulation director of The New Republic. �I hired Muslims�I hired Fareed Zakaria,� he added. The litany provoked a flash of self-consciousness. �I’m really demeaning myself here,� he said miserably, before continuing. Peretz is enough of a liberal to realize that any scene in which a man sits in the dining room of the Regency with a reporter, listing all of his friends and associates who are black or Muslim, is a scene in which that man is drowning. And yet here he was.

�What you have to understand about Marty,� says Roger Rosenblatt, the author and a friend of Peretz’s, �is that his nature came first, and the politics followed. Search the ruling passion. With Marty, the ruling passion is passion itself.�

|

|

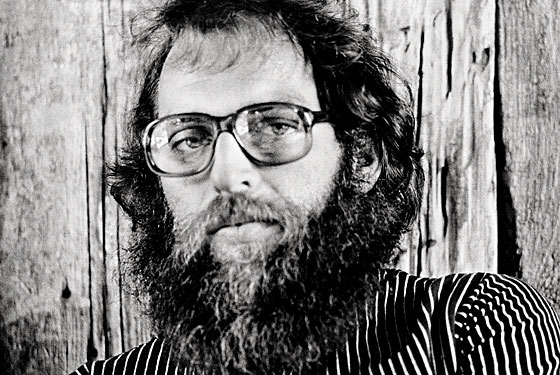

Peretz as radical, in the early seventies.

(Photo: Courtesy of Anne Peretz)

|

Peretz is nine years older than the state of Israel, and before independence, he was already dreaming of it, singing ditties for Jewish Palestine. He was raised in a family that was not religious�each Yom Kippur, his father would dance a ludicrous jig outside the synagogue, mocking the faithful�but which was deeply Yiddish. He had a difficult home life and a terrible relationship with his father, �a very belligerent man.� Peretz swore that he would be less awful to his children than his father had been to him, and he left home as soon as he could, graduating Bronx Science at 15, heading to Brandeis and then to graduate school at Harvard and a brief first marriage. Still, he held fast to a vision of home�not his parents’, at 176th Street and Grand Concourse, but Israel. �My father was a member of one Zionist party, my mother was a member of another,� Peretz says. �They had a terrible marriage, but their terrible marriage was fought over where the lines of Israel should be.�

In his twenties, Peretz’s world was the organized left. He and Anne Farnsworth became close while working on a doomed insurgent congressional campaign in Cambridge and married in 1967, each for the second time. She was a painter who would become a family therapist; she also happened to be enormously wealthy. �While there were many reasons that someone with no agenda would find Anne winning,� one of Peretz’s friends says, �for the man in question, the partner had to be rich.� Anne Peretz’s money gave the couple access rare for their age�they were, in their twenties, among the leading donors to Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign. For Peretz in particular, it allowed him the opportunity to conjure a world. They turned their house into a constant salon and gave the intellectuals who clustered around Harvard a social home.

�Arabs understand Marty: me against my brother, me and my brother against my cousin, me and my cousin against the world.�

Peretz’s ideological commitment to the left, though fervent on civil rights, had always been a little thin. By 1967, it was near total collapse. The problem was Israel. In the aftermath of the Six-Day War, some leftists had begun to see Israel as an imperial power. The black youth group SNCC circulated a pamphlet depicting the Israeli defense minister Moshe Dayan with dollar signs covering his epaulets. Peretz and Walzer wrote an essay in Ramparts, the radical magazine, trying to convince the left that it was a just war, not another Vietnam, but they could feel themselves losing the argument. The Peretzes helped fund, that year, a 5,000-person convocation in Chicago of civil-rights and antiwar activists, designed to generate a third-party ticket to the left of the Democrats. It was a disaster. A black-nationalist caucus introduced a set of proposals not only condemning the �imperialistic Zionist war� but also proposing committees to reform the nation’s �beastlike white communities.� Some delegates ordered lavish dinners, charged them to the conference, and left Peretz to pick up the tab. �I just saw a black-Jewish conflagration coming,� Peretz says.

By 1974, Peretz had found a more effective way to shape the future of liberalism: He bought The New Republic. The magazine had an august if faded history, with a politics well to the left of his own. For nearly all of the 36 years since, Peretz has kept it roughly that way, hiring editors more liberal than he and punctuating the magazine with neoconservative ideas. �Marty always wanted the magazine to be left of where he was,� Kinsley says. �He felt he owed that to the institution and his audience.�

The New Republic also served another purpose. Peretz adores collecting people. Even early in his career, at Harvard, he had assiduously cultivated the role of mentor, and his friendships with younger men were sometimes so intense that they could seem to border on the erotic. �Every so often, we’d talk about how he would sometimes grow obsessed with young men,� says one of his friends from that time. He had an equally fierce compulsion to promote them, and The New Republic soon became a platform to turn graduate students into public intellectuals. From Harvard he brought E. J. Dionne Jr., Kinsley, Hertzberg, Wieseltier, and Andrew Sullivan. His joy in their ascent was palpable: When he hired Hertzberg the second time, Peretz impulsively took him to his own tailor and paid for a bespoke suit.

At its best, the magazine was an ideologically contentious mixture that prodded liberalism and cultural criticism forward. At its worst, it could be a self-indulgent enterprise, prone to scandal, its young editors alienating its long-term subscribers. Peretz assigned stories about Israel and foreign policy. Otherwise, he gave his editors broad latitude. �I’m perfectly comfortable,� he likes to say, �with people smarter than me.�

|

|

Peretz as target: protests at Harvard, September 2010.

(Photo: Zeina Oweis/The Harvard Crimson)

|

But as the magazine, in its own irregular way, grew more modern, Peretz seemed each year to grow more ancient, more fixated on his core loyalties: Israel against the Arabs, the United States against communism, and his friends against the world. In the eighties, he was for the Contras so intensely that during a furious staff meeting, an editor, according to Peretz, accused him of being a CIA agent. (The editor in question remembers it differently; he accused Peretz only of peddling CIA talking points.) The most vivid disagreements were on foreign policy. As the Cold War ended, his staff sometimes urged restraint. �I was comfortable with America running amok,� he says.

These are not the obvious commitments of a Eugene McCarthy supporter. But the most powerful elements of Peretz’s politics have always been his loyalties. �Everything with him is personal,� one former New Republic staffer told me. �Aside from Israel, he has no meaningful policy views at all.� Peretz maintained a long campaign against John Kerry�a grudge he regrets�in large part because he �distrusted his preppiness.� Earlier this month, he defended Henry Kissinger after newly released tapes of the Nixon White House revealed that the secretary of State had suggested the U.S. not intervene in the event of a Soviet genocide against the Jews. Peretz had detested Jimmy Carter and was not fond of Bill Clinton. But he believed in his former student Al Gore very deeply. The two did not precisely share views on the Middle East; Gore �trusts the international system more than I do.� But he had traveled with Gore to Israel�Gore loved the Israeli wilderness, he says. �I think Al basically understands Israel’s problem.�

Beyond Israel, he loved that Gore loved him back. When the former vice-president conceded the 2000 presidential election, the Peretzes were at home, watching on television. To them the speech was beautiful, as sober and dignified as Gore himself. The cameras lingered, eventually following Gore outside, down the steps, and into a waiting Town Car. A minute later, the phone rang in Cambridge. It was Al, calling for Marty.

Peretz has lived in the same huge house in Cambridge for more than 40 years. But now he lives there alone, and it can seem less like a home than an art gallery. In the public spaces, Peretz has hung three works by Degas, a Cézanne, and a Flinck. But in the library where he spends most of his time�a stunning, open, two-story space�there is a display case of Middle Eastern archaeological artifacts. One day earlier this month, while on a brief visit home before returning to Tel Aviv, he showed me the objects and pulled out one in particular, a stunning, 2,000-year-old blue vase. His favorite art �in the whole world,� Peretz said, is from ancient Cambodia, particularly the elemental sculptures of the human form.

There are also two paintings of Anne’s hanging nearby, artifacts of a different sort. Peretz still wears his wedding ring. �I like old things,� he says, by way of explanation. �Anne and I were together for four years before our marriage and for 42 years in our marriage. I still love her in ways. But our values�and our lifestyles�sundered us apart.� Theirs was a complicated union. �I think for Marty there’s a difference between loyalty to a cause and a place on the one hand and loyalty to people on the other,� Anne says. �When it comes to people, it’s more about generosity than loyalty. It doesn’t mean that he’s going to stay loyal to a person forever.�

The Peretzes have been separated since 2005 and divorced since 2009, and in the long aftermath of the breakup, Marty has seemed to some of his friends less rooted. He spends more time away from Cambridge, having bought an apartment in New York and rented one in Tel Aviv. He appears, to those closest to him, more compartmentalized than ever�open, almost to a fault, and yet also hidden. �Even his children, who are very hip and very much in the stream of modern life, haven’t been able to drag Marty out of this world he inhabits, which is the history of Zionism, the history of Jews, McCarthyism,� says Ajami. �Which explains why he sometimes says things in a way that sounds off-key.�

Peretz’s attachment to The New Republic has diminished, too�having lost much of his fortune, he has been forced to sell off most of his ownership of the magazine, and he has visited its headquarters in Washington, by his own estimation, no more than ten times in three years. He began his blog shortly after Anne moved out. �The separation was the removal of pillow talk,� he says, �and while my pillow talk was much gentler than the blog, it served as a kind of � unloading.�

It often reads as a particularly pained unloading. There are some isolated moments of levity and self-awareness, such as when he referred to the Salahis�the White House party-crashers�as �Palestinian agitators.� But much of The Spine has been limited to grim reports on the intransigence of Arab or Muslim culture. One week before my visit to Cambridge, Peretz had posted a quote he called an Arab maxim: �A black face begins a black day.� One of the commenters on his site had searched and could find no record of this maxim, other than previous instances in which Peretz himself had cited it. Peretz told me he is not guilty on this small charge of fabulism: Years earlier, in the Arabian desert, he had been watching the Clarence Thomas hearings with a Saudi prince who �was always scratching his balls�I imagine he had lice,� when the prince uttered those words.

Over this past year, Peretz’s distance from the magazine has been extreme. Even to many within The New Republic, where he has been known mostly as a bullying voice on the phone, Peretz has come to be seen increasingly through the lens of The Spine. �When Marty’s name came up at TNR, it was more often than not in a mocking context,� says one former staffer. �People made fun of his blog items for being bigoted and for being incoherent.� After the controversy over his September blog post, some on the staff started pushing for Peretz to give it up.

Perhaps understanding the threat to Israel’s security requires an especially fixed lens. �The depth of the issue is�look, Ben-Gurion airport is two miles from the West Bank,� Peretz says. �The Jordan Valley��the region separating Jordan from Israel��is a dividing line between two Palestinian populations. What happens when there is no longer a king in Jordan? Obama has committed himself to a contiguous Palestine: Gaza and the West Bank. That means a discontiguous Israel.�

Peretz supported Obama in the election, but he has come to see him as a foreign-policy disaster. �I think he has set his major emotional goal to make peace between America and the Muslims,� says Peretz. �I think the American conflict with the Muslims is too complicated to make peace with in a three-point program.�

For Israel, Peretz believes in a two-state solution. But this is complicated by the fact that he also believes, and says loudly and repeatedly, that Palestine is not a real state��an utter fiction,� a �fraudulent nation-state.� The Palestinian prime minister, Salam Fayyad, has embarked on a state-building program�highways, an airport, police, a stock market�that has inspired some cautious confidence. �I am of course skeptical,� says Peretz. Fayyad is �a very modernizing person, but I would doubt that he commands loyalty.� I ask whether there is anything Fayyad can do to convince him that Palestine is a nation. It is a �very justified question,� he says. �I’m too quick to be content with the denial of being a state.�

He thinks for a minute. �Do you think that the hatred which has been polled again and again and again can be dissolved? I don’t have an answer. Maybe. Maybe.� There is another long pause. �And you have Hezbollah, I think, about to attack. Could you assume that established Palestine would not help Hezbollah? This is a question. Maybe. Maybe they would be so thrilled by having a state. But since there is really no one voice in Palestine �� Peretz’s voice trails off. He shrugs a couple of times. Then he considers the shrugs. �I mean,� he says, �a little too much of my argument is a shrug.�

�There is a level of generalization that is just wild,� says a friend of his, shaking his head. �And a certain degree of ignorance.� The Druze, a Middle Eastern people, are �congenitally untrustworthy�; �Arab society is, well�how do I say this?�hidebound and backward.� But these divisions, to Peretz, matter very much. The trouble with the progressivism of his children’s generation, he says, is that �it believes in diversity but doesn’t believe that people are really different. I believe that people are very, very different.�

A few weeks ago, Peretz agreed to give up his title as editor-in-chief of The New Republic. He will hold the title of editor emeritus and will continue to write for the magazine occasionally, but The Spine will be discontinued. He finds this abdication a relief. �I am,� he says, �exhausted.�

Peretz has never belonged to any synagogue. �I don’t know that world,� he says. His children like the liberal congregation B’nai Jeshurun, on 88th Street and Broadway, and so Peretz goes now and then. He went for Yom Kippur this year and found that during the Al Chet prayer�the traditional confession of sins�the congregation had added some of its own. �I lie, I cheat, I steal��this part is standard. �They added, �I’m homophobic. I’m lookist.’ Do you know �lookist’? We look at good-looking people. �I am ageist.’ And��here was the breaking point for Peretz��we crawl to peace and rush to war.� He shook his head. �I mean, fuck these fancy Upper West Side rabbis.�

In his seventies, Peretz’s most tangible attachments�to Harvard, to The New Republic, to Anne�have frayed, and so his primal loyalties have resettled a bit, back toward Israel, a familiar abstraction. He distrusts some of the stories his father told him, but there is one he believes in every detail. In the late fifties, when his father, Julius, was just about the age Peretz is now, the elder Peretz had an apartment in Tel Aviv. �He used to walk a lot,� Peretz says. One day, while sitting in a park, he found himself in conversation with another old man who also spoke Yiddish. The man invited Julius Peretz back to his apartment. His wife, he said, would make tei und lekach�cake and tea. So he went.

Julius Peretz had eight siblings, but all of them had died in Poland. He had emigrated to New York in 1922. On this stranger’s piano, he saw a class photo. �So there’s a picture on the piano of a group of girls,� says Peretz. �And he recognizes someone�second row, third from the left. It looks like his sister. But it couldn’t be, because the generation is a generation of younger people.� The stranger’s daughter is in the class photo, too, and they phone her. The name of the girl Marty’s father thought he recognized is Anja, and she lives�the daughter says�in a kibbutz on Israel’s edge, right up against the Jordan River.

Julius Peretz takes a taxi there�three hours, winding roads�and asks the guard to summon Anja. He does; she looks nothing like his sister. �She says, �There’s another Anja,’ � says Peretz. �He brings Anja who looks like his sister, and there is the one survivor of his family.� She was Julius’s niece. She left Poland in the summer of 1939, with two friends from a socialist youth group, and they made it to Palestine a few months later�she was 15�as their families were being annihilated. Peretz now has Israeli cousins.

In Israel, says Anne, the acts of ordinary life have a special meaning for Peretz: He will watch families playing in the park and marvel. He takes an interest in waiters, in kids on the street whom at home he might ignore. �Israel,� he says, �has been very welcoming to me.�

Comments are closed.