What’s Wrong with the Postmodern Military? After fifteen months of war, and brilliant Israeli operations, Hamas and Hizballah have managed to avoid total defeat, and the IDF has not yet managed to secure total victory. Ron Baratz

https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/israel-zionism/2025/01/whats-wrong-with-the-postmodern-military/

The October 7 attack from Gaza was not supposed to have been possible. Israelis were continuously assured by the security establishment and political leaders that Hamas was “deterred,” that Israel has an ample, sophisticated defense mechanism, and that its intelligence capabilities were second to none. And so, Israelis had to endure two shocks on that Simchat Torah morning: the large-scale surprise attack itself, which the IDF failed to avert, and the barbaric atrocities committed by Hamas terrorists and Gazan civilians.

Then came a third shock, which might surprise those who rely on English-language news from Israel’s advocates abroad, its political leaders, or the IDF’s own spokespeople: the Israeli high command required weeks to formulate plans and prepare for an operation in Gaza. Even worse, within weeks of the ground operation’s commencement, it became evident that the initial strategy was flawed, poorly planned, and exposed a staggering number of failures in preparation, training, force buildup, equipment, munitions, and execution. Although Israeli society has sprung into action to help deal with logistical problems, it became clear that the IDF was in a dire condition. To this day, a year and three months after the attack, despite numerous tactical successes and an enormous national investment in the war, both Hamas and Hizballah have managed to avoid total defeat, and despite the accomplishments of Israel’s soldiers the IDF has failed to secure total victory.

It goes without saying that Israel has an exceptional national army. Its soldiers’ fighting spirit is second to none, their bravery and commitment are likely unparalleled in the West today. But tactics and bravery alone are not enough. The strategic capabilities of the high command are essential to give shape and direction to successful military campaigns. Therefore, my aim in this essay is to examine what I believe to be the most critical aspect of the reality revealed on and after October 7: the military doctrines and national-security mindset that have led to the decades-long deterioration of the IDF’s capabilities.

To do so, I will briefly turn to the U.S. and outline two successive transformations in Western military thinking. Admittedly, this depiction will be painted in very broad strokes, but despite exceptions and counterexamples, the trend it highlights—the marginalization of classical military and operational art—is very real and increasingly troubling. I will then shift focus to Israel to examine how it has navigated these two transformative waves of strategic thinking.

How the Cold War Upended Military Thought

From the beginning of recorded history until the Second World War, national-security doctrines relied on the operational capabilities of a strong, well-trained fighting force led by a professional high command. Generals were entrusted with the responsibility of winning wars, and warfare was regarded as a specialized art and vocation. Those who excelled in defeating enemy forces rose through the ranks to become military leaders.

Military professionalism was cultivated through two key endeavors. The first was experience, gained in active combat during wartime and through rigorous training during peacetime. The second was military studies. Most great strategists were ardent students of war. They identified something constant in war, an essence that transcended time, which helped would-be generals sharpen their intellectual and vocational abilities, adopt new technologies, develop new tactics and strategies, and adapt to changing threats. Thus, military history and theory were regarded as fundamental pillars of their expertise.

When these leaders spoke of “strategy,” they referred, in essence, to planning for war—devising an operation capable of achieving victory. As Aristotle observed at the beginning of the Nicomachean Ethics: “The end of the medical art is health, that of shipbuilding a vessel, and that of strategy, victory.”

Since World War II, this understanding of the art of war has largely disintegrated in the West. The first blow was struck by the advent of nuclear weapons. In the early days of the cold war, it was widely believed that a nuclear war could not be won and that waging one would spell the end of humanity. This made nuclear war so fundamentally different from classical warfare that it seemed to necessitate an entirely new approach—one that placed prevention at its center.

At that time, when it was still possible for the U.S. to remain the sole nuclear power, some notable figures advocated for harsh measures to ensure that outcome. This was, for example, the perspective of the prodigious founder of game theory and participant in the Manhattan Project, John von Neumann, who stated in 1945: “If we’re going to have to risk war, it will be better to risk it while we have the A-bomb and they don’t.” He further added: “If you say, ‘Why not bomb them tomorrow?’ I say, ‘Why not today?’ If you say, ‘At 5 o’clock,’ I say, ‘Why not 1 o’clock?’”

When the Soviets developed their own nuclear capabilities in 1949, the prevention of war became more urgent still. The American nuclear monopoly was over, and with it, the centrality of classical military thought. The political scientist Bernard Brodie foresaw this reality, and in 1946 already predicted a major transformation in military affairs: “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other useful purpose.”

The nuclear balance of powers led to the first wave of profound transformation in national-security thought and doctrines. The entire discussion shifted: decisive military battles were replaced by the specter of total annihilation, and the key objective changed from victory to deterrence. War plans gave way to “second-strike” capabilities, and military strategy to fallout shelters. It was the hour for non-military “experts” to step up and develop strategies of deterrence by analyzing and manipulating the enemy’s state of mind. Social scientists, it was naively assumed, had the relevant tools for this purpose.

At the forefront of that transformation was the RAND Corporation, a civilian think tank established to provide guidance to the American government. The organization attracted many exceptional figures of the time, such the aforementioned von Neumann, the physicist Samuel T. Cohen, the economist Thomas Schelling, and a new generation of strategists like Albert Wohlstetter and Herman Kahn. RAND played a pivotal role in shifting national-security expertise from generals to scientists and, especially, social scientists. The new national-security doctrines were developed in quasi-academic, interdisciplinary conference settings.

The new wave of strategic thinking grew increasingly complex with each crisis, such as the launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957 or the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Complex Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) doctrines became a central feature of national-security debates, alongside discussions of escalation tactics, national interests, political incentives, societal factors, game theory, rationality, psychology, and so on. Some of these theories and detailed abstractions became so rococo as to be almost comic. Herman Kahn, for example, developed a “Ladder of Escalation” that included 44 “rungs,” while others engaged in elaborate attempts to determine the precise nuclear capability required for “minimal deterrence,” a debate that continues to this day.

Of course, the new strategic thinking had its dissenters. As early as 1957, Samuel Huntington, playing the role of the little Dutch boy trying to hold back the flood of new doctrines, wrote: “In estimating the security threats the military man looks at the capabilities of other states rather than at their intentions. Intentions are political in nature, inherently fickle and changeable, and virtually impossible to evaluate and predict.” This truth has not changed. As the strategist Colin S. Gray stated: “Deterrence will always be an uncertain and unreliable behavior, which can fail for reasons quite beyond the control of rational defense planners.”

Nevertheless, the new methodologies and paradigms were progressively being integrated into government policymaking. The process intensified under Robert McNamara, who served as secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968. McNamara embraced the RAND approach, aiming to rationalize and quantify all aspects of national defense through a social-science lens. Drawing on his business-school training and experience running Ford Motor Company, he placed significant emphasis on modern, data-driven systems analysis and the latest management techniques. Shortly after McNamara’s tenure, the prominent military historian Michael Howard remarked, disapprovingly: “One may indeed wonder whether ‘classical strategy,’ as a self-sufficient study, has no longer a valid claim to exist.” Another keen observer exclaimed: “classical and contemporary strategists enjoyed a common label only by some intellectual courtesy.”

This smug prejudice against classical strategy was, and is, a misfortune. The social sciences are ill-suited to the problems of war. True military experts have always emphasized that war is, in the words of Carl von Clausewitz, “the realm of uncertainty.” But the social scientists deny this and believe instead that they can eliminate uncertainty by developing increasingly complex abstract models. This was an Enlightenment-era folly on a grand, international—and nuclear—scale.

The full extent of this folly cannot be fully addressed here, but the crux of the problem can be outlined. To make sound policy recommendations, one must be able to make valid predictions. Unfortunately, every time the predictive capabilities of the social sciences are tested, they fail. As Seymour Martin Lipset, one of the greatest sociologists and political scientists in American history, candidly admitted in 1985: “None of the social sciences can predict worth a damn. . . . We tried to make predictions, and they didn’t work out.” This conclusion was further reinforced by an unparalleled twenty-year empirical study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania professor Philip Tetlock.

It would be wrong to say that nothing good came out of cold-war-era national-security thought. Nuclear weapons indeed posed new sorts of challenges that called for new thinking. Many great minds were brought into the national-security conversation. Rational accountings of military operations improved civilian oversight. But the downsides were tremendous. Conventional war was relegated to a secondary role, resulting in a continuous decline in both material and intellectual capacities. Scientific and managerial approaches took precedence over war leadership and military strategy. On paper, this new approach appeared more elegant and efficient, but wars are not fought on paper.

The toll that the new national-security doctrines took on the military became glaringly obvious during the Vietnam War, under the leadership of McNamara and General William Westmoreland. The overarching strategy was one of attrition—a concept that, as many military commentators observe, reflects the absence of genuine strategy. Lacking a decisive strategy, the war relied on “search and destroy” operations, which were essentially temporary raids that inevitably ended in retreat. This approach pushed the U.S. army to the brink of collapse and highlighted a profound decline in its strategic and operational thinking.

Perhaps the greatest demonstration of the folly of the new approach comes, paradoxically, from the collapse of the Soviet Union. The entire array of social scientists, intelligence agencies, and complex models—lavishly funded to analyze Soviet affairs and the Communist party’s behavior—were caught completely by surprise. It turned out that they had been fundamentally wrong in their assessments; it was self-delusion masquerading as a national-security doctrine. A few notable figures, such as the distinguished Sovietologist Richard Pipes, admitted as much and requested a critical examination of this failure, but few took notice.

We can summarize the first wave of change in national-security thought thus: military strategy and generalship gave way to deterrence theories and social science. The pessimism surrounding nuclear war led to an exaggerated optimism about the social sciences’ applicability to the problems of national security. Now the vocabulary of national-security doctrines was dominated by non-military theories and formulas.

Nevertheless, most national-security experts of this period were realists. They viewed the world in terms of power and national interests. War was still considered a possible, if not plausible, outcome of international affairs. Therefore, the army and its generals still retained a place of significance and were tasked with maintaining capabilities for sub-nuclear or conventional war scenarios, such as a Soviet invasion of Western Europe or a deterioration in Asia. This, too, was about to change.

The Rise of the Postmodern Military

If the cold war had a deleterious effect on military thinking, the effect of the post-cold-war era was even worse. On December 25, 1991, the Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, and the red hammer-and-sickle flag flying over the Kremlin was replaced by the three-color Russian flag. The USSR was no more. President George H.W. Bush gave a Christmas victory speech and declared that the “confrontation is now over” and “our enemies have become our partners.”

The change in the international climate was powerful and swift. It felt like “the end of history,” the title of Francis Fukuyama’s book, published in 1992. As early as June of that year, then-UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali proposed that the UN assume responsibility for maintaining “international peace” by upgrading its “security arm.” This proposal envisioned the UN taking over the role of maintaining the new “world peace” from individual states.

Western states were already eager to minimize their armies, cut defense budgets, and reap the so-called peace dividend. Germany provides a good example of this trend. At the beginning of the 1990s, more than half a million Germans served in the Bundeswehr for fifteen-month stints. With the collapse of the USSR, Germany began downsizing its army and reducing the length of service. By the end of the 1990s, conscription had been shortened to ten months, and the army had roughly 300,000 soldiers. By 2011, conscription—then at six months—was suspended, and the army was reduced to fewer than 200,000. Today it is even smaller, but due to the war in Ukraine, Germans are contemplating reintroducing conscription and reforming the Bundeswehr to make it, in the words of Defense Minister Boris Pistorius, “war-capable” (kriegstüchtig).

Military spending as a percentage of GDP in the fourteen Western NATO countries in 1990 (excluding Iceland, which does not have a military; and Turkey) tells a similar story. In 1970, the average spending was 3.35 percent of the GDP; by 1990, it had decreased to 2.65 and by 2015, it reached its lowest average of 1.5. After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, NATO heads of state met in Wales and issued a declaration pledging to raise military spending to at least 2 percent. In practice, most have failed to meet that commitment. The United States is the biggest military spender, but it too follows the same pattern: from more than 8 percent of its GDP in 1970, it went to spending 5.61 percent in 1990 and 3.46 percent by 2015.

This was the second wave of transformation in national-security doctrine. With the USSR gone, it was believed that the likelihood of conventional war had dropped to near zero. The only threats that remained were “asymmetrical wars,” in which enemies are small third-world states and paramilitary forces. National-security concepts shifted from wars that can’t be won to wars that can’t be lost.

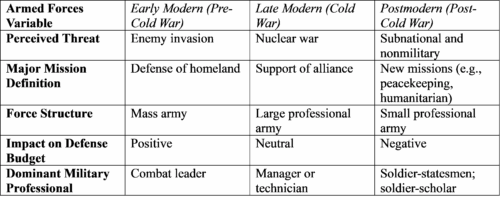

Charles Moskos, the renowned military sociologist, provided an impressive articulation of the new shift in military affairs. As early as 1994, he distinguished between three types of armies: early modern (pre-cold war), late modern (cold war), and postmodern (post-cold war). The differences were quite stark across an array of substantive variables:

By now, a new phrase entered the national-security lexicon: “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA). The combination of improved information and communication technology with precision munitions and other advanced weaponry, the argument went, had transformed warfare, enabling the technologically advanced U.S. to maintain significant military advantages at much lower costs and with reduced manpower.

With the advent of the RMA, a new set of alleged military doctrines emerged, accompanied by a flood of sophisticated-sounding acronyms such as “network-centric warfare (NCW), “effects-based operations” (EBO), “systemic operations design” (SOD), “precision guided munitions” (PGM), “operations net assessment,” “collaborative information environments,” “standoff firepower,” and “system of systems.”

The paradigmatic articulation of this approach can be found in a 1996 book by Harlan K. Ullman and James P. Wade, titled Shock and Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance. The new technology, Ullman and Wade argued, could “destroy or so confound the will to resist that an adversary will have no alternative except to accept our strategic aims and military objectives.” To do so, one must “control what the adversary perceives, understands, and knows, as well as control or regulate what is not perceived, understood, or known.” The “psychological and intangible” have become the focus of military attention.

One might describe the new doctrines as adapting the cold-war social-science conceptual and theoretical framework, designed to analyze and influence heads of state, and applying it to the asymmetrical battlefield. According to the new paradigm, the battlefield is first and foremost mental. Whereas conventional military thinking focused on destroying the enemy’s military capabilities, hopefully breaking his fighting spirit as a result, the new military concept aimed to shortcut the process by aiming directly at the adversary’s will. Once again wishful thinking replaced strategy and jargon replaced common sense. Influencing the enemy’s consciousness, through various manipulations and precision strikes designed to create specific psychological effects, was thought to be the path to victory.

In truth, these ideas were controversial from the outset. But they became highly popular in the post-cold-war climate of liberal internationalism, particularly among decision-makers. The belief that we could finally eliminate the “fog of war” and win decisively by circumventing the most difficult aspects of violent conflict was very tempting. In the demilitarizing world, “RMA” became a doctrinal buzzword, guaranteeing funding and recognition.

The failings of this new approach became evident during a massive and unprecedented wargame in 2002, conducted under the aegis of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, “to explore critical warfighting challenges at the operational level of war.” The congressionally mandated Millennium Challenge 2002 cost $250 million and involved over 13,500 soldiers in 25 locations. As the final report stated, it was “the most extensive and realistic assessment of our concepts to date.”

In this exercise, the red team, playing the role of the enemy, was led by the capable Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper. Thinking in more traditional terms, he kept his communications below the threshold of digital detection and interference, and attacked the blue team (representing the U.S.), foiling its initial campaign and inflicting heavy (virtual) losses. In response, the game was restarted, with various restrictions imposed on the red side.

Van Riper refused to participate, and the game concluded with a blue victory. The now-declassified report admits that “free-play was eventually constrained to the point where the end state was scripted.” In short, in this huge simulation, a force equipped with the new technologies and doctrines was unable to defeat decisively a force led by a capable commander.

Proponents of RMA claim that these doctrines were also put to the test in the 2003 Iraq war. But that is hardly convincing. The Bush administration deployed about 150,000 troops, with Britain contributing nearly 50,000 more. This was a significant force, and it succeeded in defeating Saddam’s army, which was technologically overmatched and impoverished by years of sanctions. This was hardly a great feat. Moreover, the insurgency that followed suggested that the “shock and awe” tactics did not reshape the psychology of America’s enemies. As Bush discovered the hard way in 2007, defeating the insurgency would require the very traditional strategy of sending additional troops—what became known as the Surge.

The defeat of the Iraqi army has, if anything, more in common with the recent success of Abu Mohammad al-Jolani’s Islamist militia, which hasn’t benefited from cutting-edge military technology, and certainly is operating without knowledge of RMA theory or “shock and awe” doctrines. Jolani’s militia easily swept away the Syrian regular army, because much like Saddam’s paper-tiger army, the latter existed more in theory than on the battlefield.

To summarize the second wave of military transformation in terms of doctrine, today’s generals conduct special operations and embrace militarily revolutionary and asymmetrical theories rooted in the poorly founded assumptions of the social sciences—assumptions that are likely to collapse when tested in the reality of war, as they have in Israel.

Technological advances have always been a significant benefit to militaries and some new tactical and operational ideas can be advantageous on the battlefield. But such innovations do not compensate for, or replace, the loss of operational art. And yet Western militaries have convinced themselves that a radical historical shift in warfare has rendered this art obsolete. As things currently stand, it is doubtful whether Western armies could win a conventional war against a capable enemy.

Israel’s National Security

The first person to think systematically about the Jewish state’s need for an organized fighting force was Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who in 1915 founded the Zion Mule Corps and, in 1917, the 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, better known as the “Jewish Legion.” Following in his footsteps was his political nemesis, David Ben-Gurion.

More than anyone else, Ben-Gurion, a gifted autodidact in matters of war, is responsible for shaping the early years of the IDF and its strategic thinking. Ben-Gurion is sometimes reported as having said, “In Israel, if you don’t believe in miracles, you are not a realist.” While the authenticity of that quote is disputed, there is no question that in 1948 he wrote: “There is one thing in which one must never put his faith in miracles, and must calculate calmly and cruelly—and that is war.”

As a national leader, Ben-Gurion thought about national security in a broad sense, encompassing aspects such as economics, education, and agriculture. He was however acutely aware of the need to differentiate the political level of national security from the military one and understood the importance of cultivating the specific operational professionalism required in the leaders of the IDF.

For Ben-Gurion this presented the nation with an existential problem, since he foresaw that declaring a Jewish state would trigger a military campaign by Israel’s Arab neighbors, and realized that the Haganah—the pre-state-era defensive force—primarily had a guerrilla experience and mindset. He addressed this issue by founding the IDF, placing in key positions officers who had conventional military education and experience, often gained from serving in foreign armies during World War II. Thus, the IDF’s strategic and operational thinking was imported and adapted from war-tested British and, indirectly, German doctrines.

Ben-Gurion, above all, deserves credit for the principles that defined Israeli military strategy for much of its existence. Due to the conventional military asymmetry favoring Israel’s enemies and its small geographical dimensions, Israel should, when a threat looms, aim to launch a preemptive attack. If the enemy attacks first, the standing Israeli army must block its invading divisions while the reserves organize a counterattack, pushing the battle into the enemy’s territory and destroying its forces. Wars must be quick and decisive. For such a doctrine to work, the IDF would maintain the highest capabilities and preparedness, and employ commanders who were masters of the operational arts.

None of this was ever formalized in an official national-security doctrine, but these principles were evident to anyone paying attention. While the U.S. was invested in the strategic thinking of the cold war, Israel fought conventional wars in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982. Battle-earned experience compensated for the lack of high-level military study that has always plagued the IDF high command. Bad ideas (referred to as “conceptions” in Israeli parlance), such as overreliance on intelligence assessments or the Barlev line of defensive outposts near the Suez Canal, easily overrun by the Egyptians in 1973, were empirically tested by Israel’s enemies—and proved flawed.

In short, the IDF was war-oriented, and from that focus came operational preparedness. For the most part, its generals thought about war, ensured their forces and war plans were well prepared, and engaged in heated debates about operational alternatives. This was their mission; this was their mindset.

As an example, one can cite remarks made by Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin on June 29, 1967, in a closed meeting with the general staff after the Six-Day War, inadvertently giving us a glimpse into the practices and discussions of the Israeli high command.

In retrospect, we confronted what we called in our operational plans “the case of everything.” . . . I remember many discussions, [including] a symposium less than a year ago about breaking through [enemy lines]. We had two opinions, and in the war, [each commander] carried out his own thesis: Talik [Israel Tal]—an armored battle in daytime with the air force neutralizing the enemy’s artillery; Arik [Ariel Sharon]—a night battle, with paratroopers enveloping and neutralizing the artillery. In fact, . . . both proved to be valid when we properly prepared. . . . Lastly, I think it is certain that during the war we proved one thing that we always tried to make our motif, which is that the army will be an enabling, and never a debilitating, factor for the political leadership to decide what it wants.

These remarks shed light on how the IDF leaders of that era perceived their craft. The IDF was a war machine designed to prepare for the worst-case scenario. Its generals focused on developing the most effective operational doctrines and war plans to provide political leaders with the best possible military tool. They spent little time on concepts such as ladders of escalation, psychological effects, or the nuances of deterrence. Their primary objective was to defeat the enemy’s army, and, truth be told, they accomplished this goal when it was required.

The IDF Goes Postmodern

While the ideas of cold-war-era strategic thinking for the most part bypassed the Israeli security establishment, those of the 1990s RMA did not. On the contrary, they hit it hard.

The best way to illustrate what has changed may be to contrast Rabin’s general staff with today’s. For more than a decade, the Israeli security establishment has defined only two conventional threats that the IDF should be prepared to address: Hamas in Gaza and Hizballah in Lebanon—both terrorist organizations. At some point, the bar was set even lower: the IDF should be capable of attacking only one organization while maintaining a defensive posture against the other. This perspective is fundamentally flawed, given that Israel has politically unstable neighbors with significant military capabilities and extreme Islamist factions that could rise to power at any time. But the security establishment does not find this troubling.

It gets even worse. Although Hamas was defined as a threat, after October 7, 2023 it turned out that the IDF had no current operational plans for an invasion of the Gaza Strip. The commander of the Gaza division, and later of the entire Southern Command, had decided such plans were redundant. The general staff and the Operations Directorate (which is responsible for keeping track of such plans) apparently approved, and the Cabinet ministers were either oblivious or compliant. The same high-ranking officer, by the way, was promoted and now holds an even more prestigious position in the IDF’s general staff.

This is far from an isolated case of underperformance by current Israeli generals that likely could not have happened before the 1990s. The pattern of decline is well known to the few who have closely followed the security establishment, although its consequences have become publicly visible only in 2023. National-security leaders, wielding a massive and expensive apparatus, failed Israel. They did not plan, they did not build, and they did not prepare for war. Operational readiness was lacking, trained forces were scarce, and relevant intelligence was missing. The so-called security professionals have become bureaucrats in uniform, plagued by all the ailments typical of large, unaccountable government agencies.

It is true that in a democracy, ultimate responsibility lies with the political leadership, which has been predominantly right-wing in recent decades. Indeed, the politicians bear full responsibility and have completely failed in their oversight. And yet, putting politics aside, the main problem stems from the lack of military professionalism. After all, had the professional leadership been competent, the politicians would not have prevented them from performing better. Thus, the main question remains: how and why did the national-security experts lose sight of their profession?

Truth be told, these are not easy questions to answer. Let me illustrate through an anecdote. A few weeks ago, I participated in a discussion in a Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense sub-committee. The topic was the working definitions used by the Israeli security establishment—the IDF, the Ministry of Defense, and the National Security Council—for various operational and strategic terms. As expected, there were no real answers to the questions the committee was posing, but there were two telling explanations of why there were no answers. One senior National Security Committee member told us that such matters are “Oral Torah”—the rabbinic term for the traditions passed down from generation to generation—while his IDF counterpart claimed the information was classified.

Those answers perfectly exemplified the difficulty to track doctrinal transformations in Israel. Changes in the security institutions are either kept secret—often to shield them from public and professional criticism—or deliberately kept opaque, which dissipates responsibility and undermines professional standards. Information is therefore scarce, no one is accountable, and everything is in flux and susceptible to capricious change.

And yet, we are not entirely helpless. Sometimes, especially during national emergencies, the main products of the system are publicly displayed, allowing us to reverse-engineer the manufacturing process. Some critics reach back as far as the 1980s and the First Lebanon War in searching for the origins of the decline, but when focusing on doctrinal issues, I believe the most important point of transition was the “peace process” of the Oslo Accords in the 1990s.

Shimon Peres, the foreign secretary at the time and the chief architect of Oslo, gathered around him a cadre of academic political scientists who were deeply entrenched in what might be called the end-of-history mindset and who played instrumental roles in shaping the peace process—among them Yair Hirschfeld, Ron Pundak, and Yossi Beilin. Under their leadership, the army was repeatedly instructed to “change the disk.” That phrase meant, on the surface, to stop viewing the PLO as an enemy and treat it as a peace partner, but it also carried a deeper meaning of transforming the role of military leaders. They were to become what Charles Moskos termed “soldier-statesmen”—peacemaking figures who carried themselves like diplomats, serving in the new, postmodern army.

Peres and the political scientist Arye Naor justified this process in their book The New Middle East. The book was a masterpiece of wishful thinking, built on the quicksand of liberal internationalism, against which the army elite had neither the political and personal inclination to resist nor the intellectual fortifications to support such resistance. After all, it is always tempting to be a statesman striking international peace deals instead of a soldier devising battle plans.

And so, the national-security establishment embraced the new, post-cold-war agenda, articulated in Peres’s book and proliferated by his cadre of political scientists: conventional wars were over; the only threats that remained were missiles and terror; technology would overcome all possible threats; and concepts such as strategic depth and maneuvering divisions are obsolete. All that remained was for the military heads to beat their swords into plowshares and make peace. The “end of history” had made aliyah.

It was around this time that Israeli pseudo-intellectuals began writing about Israel’s national-security doctrine as if it had always been a “triangle” consisting of “deterrence,” “early warning,” and “decisive victory.” This is not only untrue but also inherently flawed when it comes to the IDF, as two of these three elements undermine the military’s primary purpose: to be prepared for the eventuality that both deterrence and intelligence fail and the enemy attacks unexpectedly.

Another personal anecdote might help illustrate this failure. I write a column for the Israeli weekly Makor Rishon. On the Shabbat of September 30, 2023, the week’s issue was focused on military intelligence. Using historical examples, I wrote about the folly of basing strategic decisions on intelligence assessments, and concluded:

The military must assume—despite our vast and expensive intelligence systems—that when a war breaks out, we will be surprised at all levels. The historical lesson is unequivocal: one must not rely on intelligence assessments, should only refer to the enemy’s capabilities (and even here, with modesty), and take into consideration unexpected and challenging scenarios.

The following Shabbat, thousands of Hamas terrorists infiltrated Israel, catching the entire security establishment by surprise. The whole world witnessed the tragedy of abandoning this evident national-security principle and replacing it with the empty social-science hubris that haunts the intelligence community.

The Israeli public was repeatedly assured that Hamas was “deterred” and that both the nation’s defensive measures and its understanding of the enemy’s interests and intentions were impeccable. This guarantee was an unprofessional conceit, revealing deeply flawed national-security practices. The most troubling aspect, however, is that the military was not adequately prepared to address what should have been its most fundamental objective—on a front it had itself defined as hostile.

Let us now go backto the journey of deterioration. In 2004, former Minister of Justice Dan Meridor was tasked by then-Defense Minister and former IDF chief of staff Shaul Mofaz, along with then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, to provide Israel with a formal, written national-security doctrine. Meridor, a diligent, articulate, and sophisticated empty suit, compiled a report reflecting the views of all the high-ranking security-establishment leaders. In essence, this report formalized the de-facto doctrine, the “Oral Torah,” that had already been employed by Israel’s security institutions for a few years.

It later became clear that the secret report celebrated a significant RMA transformation the IDF had undergone. Two excerpts from a subsequent report issued by Meridor highlight this point:

The threats of conventional war risks have decreased, and the risks of sub-conventional confrontations (guerrilla and terror) and super-conventional confrontations (non-conventional weapons) have increased.

The committee believes that changes in the strategic environment and the shift of the confrontation’s center of gravity from the conventional battlefield to asymmetric spaces require a re-examination of the basic elements of the “security triangle” and highlight the need to add a fourth element—“defending”—in light of the rising threats to population centers.

The emphasis was clear: the military’s traditional national-security objective—namely, to fight and defeat the enemy—now constituted only a fraction of this hyper-modern, pseudo-militaristic approach to national security. As a result, the IDF reduced its main fighting forces, doctrinally compensating for this decline in capability by adopting “shock and awe” theories. The bulk of its focus shifted toward intelligence, technological innovations, and defensive capabilities.

While the report was being written, Israel disengaged from Gaza, an operation carried out by the new chief of staff, Dan Halutz, a fighter pilot and former commander of the air force. Halutz was the perfect fit for the new approach, and had declared in 2001, “I maintain that we have to part with the concept of a land battle. . . . Victory is a matter of consciousness. Air power affects the adversary’s consciousness significantly.”

The classified Meridor report was submitted to Shaul Mofaz in April 2006, but unfortunately for the security establishment whose views it consolidated, it was quickly put to the test when war broke out with Hizballah in July.

Probably never in the history of similar reports had such an elaborate and extensive document, representing such a wide range of “professionals,” been so thoroughly and quickly debunked. The war proved, beyond any doubt, that the security establishment and the IDF were completely misguided. “Soldiers were deficient in training, and equipment, and senior officers seemed woefully unprepared to fight a ‘real war,’” wrote an American observer. The heads of the Mossad and Shin Bet told Prime Minister Olmert that “the war was a national catastrophe and Israel suffered a real blow.” Indeed, it was the worst military campaign Israel had ever waged.

The underlying problem was not the poor performance of the IDF, but the misguided military doctrines that caused it. Two formal commissions of inquiry were appointed after the war—one headed by the former supreme court justice Eliyahu Winograd and the other by the former chief of staff Dan Shomron—and both were unequivocal in their conclusions: in terms of strategic doctrines, the IDF and the security establishment were fundamentally out of touch with the reality of war.

The Winograd commission had a broader remit, reviewing not only the IDF’s actions but also political decision-making, international law, and other aspects of the war. Yet its findings on the matter were unequivocal:

The army in its entirety . . . failed to supply a satisfying military response to the challenge presented by waging war in Lebanon, and failed to supply the political leadership a proper military foundation for its political action. . . . The basic recognition that one of the primary objectives of the IDF and its fighters is to prepare for war . . . has been eroded.

The Shomron report focused narrowly on the military and its doctrines. The committee members were shocked to discover that the IDF had transformed itself into an RMA-style army. As Shomron wrote:

Between 2000 and 2006, the IDF developed a new operational doctrine intended to replace its traditional one. This new doctrine relied on precision fire to create levers and effects on the enemy’s consciousness, rendering large ground-maneuver operations in the enemy’s territory unnecessary.

It also turned out that in the two years prior to the war, the IDF conducted two exercises to test and implement the concept of “winning through effects and levers,” professionally known as “effects-based operations.” These exercises, in fact, resulted in failure, but no one wanted to learn, least of all Moshe Ya’alon, the chief of staff in 2004, and Dan Halutz, his successor.

And so, it turned out that the IDF had become what Moskos termed a postmodern army. It implemented “shock and awe” doctrines, attempted to “engineer the enemy’s consciousness” through symbolic acts, and focused on deterrence, precision fire, small “network-centered” forces, and a lot of air power. Along the way, it forgot how to achieve military victory, even when wielding its overwhelming superiority against a few thousand Hizballah fighters. The general staff’s new doctrine replaced victory with an “image of victory,” and achieved neither.

The committee recognized that most of the senior staff at the time lacked knowledge of traditional military thought, and recommended significant personnel changes, along with educating a new cadre of leaders, to implement what might be called a counterrevolution in military affairs.

The frustrated Shomron later said: “We used to hit the enemy on the head with a club—and then he felt the effects.” But the postmodern IDF’s approach was to try to reach the “effects” stage without the intermediate clubbing phase, which, unsurprisingly, turned out not to work in the real world.

Perhaps the best doctrinal articulation of what Shmron’s committee found was provided by Matt M. Matthews, a former army officer and historian writing for the U.S. army’s Combat Studies Institute, with the aim of helping the U.S. army to avoid Israel’s mistakes:

[I]n the years following its withdrawal from southern Lebanon, the IDF began to embrace the theories of precision firepower, effects-based operations (EBO), and systemic operational design (SOD). EBO emerged out of the network-centric warfare (NCW) concept in 2001, with the publication of a white paper by the U.S. Joint Forces Command (JFCOM). At its core, EBO is designed to affect “the cognitive domain” of the enemy and his systems, rather than annihilating his forces.

The Second Lebanon War was a wake-up call for me as well. In 2007, I wrote two lengthy essays in the now-defunct journal Nativ. One discussed the lack of vocational military education for the IDF’s high-ranking officers, and the other, titled “The Return of the Ground Offensive,” argued that the IDF must regain its lost operational capabilities, and warned that the new ideas dominating it had proved disastrous and must be replaced. After October 7, the essay resurfaced due to the following passage:

There is no escaping the conclusion that Israel today . . . is a state with a strategic concept not of active defense, but of [passive] protection. It speaks of winning without waging war and of a sterile victory, achieved by intelligence and firepower entrusted to a well-armed security guard. All seems well until the moment the enemy’s forces simultaneously infiltrate the penetrated border at several locations, [entering] directly into villages and military bases—and then it turns out there is no significant, sufficiently trained force that can oppose them and fight like an army.

On October 7, it pains me to say, this prediction came true.

Failing to Learn the Lessons of Lebanon

How did this prediction from 2007 remain so relevant in 2023? Let us go back to the fiasco of the Second Lebanon War. The now-discredited Meridor report was never formally approved and was buried under classification. With two damning commission reports and an undeniable failure, the security establishment put on a show of addressing the problems. Halutz was removed, along with a few other commanders, and Gabi Ashkenazi was appointed chief of staff. Some retired officers were brought back to teach the younger generation, and it appeared, on the surface, that things were improving.

This reshuffling, however, turned out to be a mere facade put on by a national-security establishment refusing to admit its shortcomings. Chief of Staff Ashkenazi, like Ya’alon and Halutz before him, and Benny Gantz, Gadi Eisenkot, Aviv Kohavi, and the current chief of staff Herzi Halevi after him, lacked both the intellectual and practical tools to address the issues at hand. Every chief of staff since Ya’alon has been cut from the same cloth: special-operations enthusiasts, deeply influenced by RMA doctrines. They have minimal background in military studies and harbor an unconscious belief that they are somehow experts in social sciences and international affairs. They have had no desire to fix what they do not perceive as broken, nor any knowledge of how to fix it had they wished to.

Take, for example, Gadi Eisenkot, who in the 2006 war headed the IDF’s Operations Directorate, meaning he was in charge of operational plans. Eisenkot was a vocal opponent of any large-scale ground maneuver. His operational doctrine and Halutz’s were almost indistinguishable. Early in the campaign, he advocated for symbolic actions: “We need to take a village . . . and put a battalion in it. What’s important is the symbol, the ability to do it and break the myth.” Halutz responded: “I accept this approach entirely. . . . I do not approve at this time a large-scale ground operation. It would also be a pity at this time to waste many resources planning it.” To the very last day of the war, Eisenkot remained the only general-staff member who opposed a significant ground maneuver, waiting, instead, for international intervention to end the war. His operational philosophy was: “For me, land is a burden. Therefore, the operational pattern is—raids. You go in and out.”

In the end, the air campaign failed to achieve its promised goals and Eisenkot’s comrades overruled him and sent a ground force to maneuver deep into Lebanon—but to no avail; it was already too late. And yet, although Eisenkot contributed to shaping the IDF’s worst campaign to date, he was promoted to chief of staff in 2015.

This should be inconceivable. Eisenkot is like the head of a hospital’s surgery department advocating for an alternative “revolutionary” medical theory, refusing to prescribe medication or perform surgeries, and instead treating patients’ “cognition” and “consciousness” through “symbolic” medical effects—and then being promoted to lead the entire hospital. But the Israeli security establishment operates by its own set of rules.

Indeed, Eisenkot is not alone. Take, as another key example, the operational concept outlined by Benny Gantz, who preceded Eisenkot as chief of staff and had been the head of the IDF’s ground forces during the Second Lebanon War. I’ve translated it literally, because it sounds every bit as incoherent in its original Hebrew word salad:

I suggest transitioning to an offensive piano in a manner in which you take one focused, defined area, you announce it and do it. “Tomorrow Tibnin” [a Lebanese village], and tomorrow do. “The day after tomorrow Zibkin” and the day after tomorrow do. Every time a different place. You don’t settle in Lebanon. There will be concentrated efforts, each time in a different place. . . . And when you come back you bring the guys to sing with singers at night. Nothing happened. You say: “I have time. I don’t even intend to place anything here long term.”

Some Israeli chiefs of staff have been more sophisticated and articulate than Gantz—who went on to serve as defense minister from 2020 to 2022 and today plays a leading role in Israeli politics—but in terms of military doctrine, they all share the same approach.

Understanding the military doctrines that have shaped these leading Israeli security figures, it is hardly surprising to find, to this very day, that the IDF’s operational idea in Gaza and Lebanon remains a similar pattern of raids, which continue to fail. Thus, fifteen months after the war began, a battered Hamas still controls Gaza and Israel is raiding the same places a week ago where it fought in the fall of 2023. Hamas, as the latest reports reveal, has in the meantime recruited thousands of new terrorists.

The Israeli version of the revolution in military affairs was profound in the deepest sense: its adherents are unaware that they are revolutionaries. This is why the supposed implementation of the committees’ findings after the Second Lebanon War was an empty feat, why the system quickly reverted to the spirit that Meridor promoted in his report, and why reports from 2007 read as though they were written about 2023.

The last chapter in this story is 2014’s Operation Protective Edge in Gaza. Netanyahu was prime minister, Moshe Ya’alon—the failed former chief of staff—was security minister, and Benny Gantz chief of staff. Prior to 2023, this was the largest of Israel’s numerous mini-wars against Hamas following the withdrawal from Gaza: it lasted nearly 50 days and involved hundreds of thousands of Israeli soldiers and the entire might of the IDF, fighting against a much less dangerous force than Hizballah—and achieving very little. After the operation, Hamas remained intact to rebuild and expand its war capabilities, while Israel constructed the defensive slurry wall, which created a false sense of security and allowed Hamas to strengthen its forces further.

Protective Edge was a precursor to the current war, but that should hardly surprise the reader by now. Netanyahu, like Ya’alon, Gantz, and all their peers in the security system, are integral parts of the same unchallenged and failing paradigm that replaced Israel’s military capabilities with fanciful, postmodern, high-tech, and social-science-influenced doctrines.

Ya’alon is another good example for the system’s inability to learn from its mistakes. In 2011, as minister of strategic affairs, he continued to assert—despite his failures in the 2006 war—that there is “an iron wall of consciousness according to which we are unbeatable on the conventional battlefield.” And in 2017, after also failing as security minister during Protective Edge three years earlier, he repeated that there are no conventional threats, only “non-conventional threats, like the Iranian nuclear threat, or rocket fire.”

This is dogmatism in its essence. Ya’alon, like his peers in the security establishment, is baselessly confident and arrogantly ignorant. His flawed analysis led to the further degradation of Israel’s war capabilities, as did all subsequent heads of national security. After the visible failures of 2006, 2014, and 2023–24, the military leaders showed no inclination to reconsider their dogmas. Worse, their failures seem to be rewarded with promotions and political careers rather than punished.

I saw this dogmatism up close when I served in the Prime Minister’s Office in 2016 and 2017. Among my responsibilities was composing a report to the state comptroller about cabinet decision-making before and during Protective Edge. I was privy to the relevant classified information, as well as to the subsequent military and cabinet responses to the threat from Gaza through 2017. I witnessed firsthand, in government and closed cabinet meetings, the decision-making process. And I saw that nothing had really changed since 2006. The post-cold-war RMA thinking was still in full force. The maneuvering army continued to shrink, conventional capabilities were vanishing, and the focus on intelligence, technological innovations, cyberwarfare, and defensive measures kept growing—along with pension benefits and salaries for high-ranking officers.

The security establishment was investing time, energy, and resources in projects that achieved little—not Potemkin villages, but Potemkin cities. Take, for example, the sophisticated and costly slurry wall along the Gaza border, which was easily breached with bulldozers on October 7. It epitomized the defensive “fourth leg” of Meridor’s national-security doctrine. Almost all lower-ranking IDF officers and security advisors admitted to me, behind closed doors, that they didn’t believe it was a worthwhile investment. But the higher one went in the hierarchy, the more support one found for this modern-day version of the Maginot Line.

The mutual interests of the politicians and the security establishment worked seamlessly to mislead the public about the state of national security. Prime ministers, defense ministers, and general-staff officers gave nearly interchangeable speeches with the message, “We are the mightiest nation; our enemies tremble with fear; our national security is flawless,” with much jargon and bravado mixed in. This rhetoric cuts across the civil-military divide and across party lines: Moshe Ya’alon, Benjamin Netanyahu, Naftali Bennett, Benny Gantz, and Yoav Galant are virtually indistinguishable in this regard.

The Victory That Wasn’t

I have tried to highlight what I believe are the main milestones in the West’s and Israel’s military decline, about which much more can, and should be, said. Ben-Gurion’s critical and cautious approach to national security, particularly its military aspects, is long gone—along with conventional war doctrines and a strong operational army.

It might be argued that Israel is winning against Hamas and Hizballah, and thing aren’t so bad as I claim. After all, since October 7, the IDF has waged wars against both terror organizations as well as their masters in Tehran, and appears successful.

I do not share this view. Yes, Israel has, over the last months, achieved much, and the IDF had many tactical successes. Yet the appearance of overall, strategic success is misleading for three primary reasons.

First, on Mida, the website I founded in 2012, Akiva Bigman—a researcher, investigative journalist, and Ph.D. student in military affairs—has compiled the most thorough operational and doctrinal report to date on the IDF’s ongoing campaigns in Gaza and Lebanon. The findings are devastating: lack of preparation, poor planning, severe shortages even in basic fighting equipment, dysfunctional battle processes, failures in command, operational incompetence, and lack of a comprehensive strategy have plagued the war from its outset. The IDF’s successes are mostly not due to operational competence but rather to the fighting spirit of the Israeli soldiers on the ground and the massive asymmetry between the IDF and its sub-military opponents, Hamas and Hizballah.

Second, let us examine the situation strategically. Fifteen months into the war, 30 percent of the Gaza Strip—a small territory of merely 140 square miles—has never been entered by the IDF. An additional 40 percent remains free of an IDF presence, because Israeli forces continue a cycle of raiding and withdrawing. Although its military capabilities have been diminished and part of its leadership eliminated, Hamas still retains control over most of Gaza and over its entire population. This situation is not dissimilar to Lebanon, where tactical successes ultimately resulted, under American pressure, in a ceasefire agreement that ensured Hizballah’s survival and subsequent rehabilitation.

Third, when we do what the Israeli security establishment hates to do—factor costs into the equation—we must conclude that, relative to the national investment in the war, it has been incredibly inefficient, especially when one considers that war with these two terror organizations was precisely what the IDF was supposed to prepare for with its $20 billion annual budget. Yet, instead of building a war machine capable of quickly deciding the conflict, Israel has had to allocate massive additional funds—which result in a massive, long-term national debt—and fifteen months later, the situation remains unresolved.

In short, the tactical victories—expected in asymmetrical wars—have not amounted to a strategic achievement. This is a case of underperformance on an alarming scale, with huge costs not only in treasure but in blood. With such massive inputs and limited outputs, the IDF of the 1950s to the 1980s would hang its head in shame. The lack of strategic thinking and competence in operational art led, as is often the case, to attritional raids. While these raids may be tactically impressive, they fail to deliver a lasting strategic impact.

This is why Israel must return to a classical military mindset. The next war might not be as asymmetrical as the conflicts against Hamas and Hizballah. Such a war would require a fundamentally different army and a restored operational art—not the weakened IDF and degenerated command currently in place. And if another asymmetrical war arises, that reformed army would still be capable of fighting it. The reverse, unfortunately, is not true.

Israel must urgently rebuild its security forces. Since an army is only as good as its command, the first priority must be reforming the intellectual military education of our officer corps. Our generals should be educated in military affairs, so they are not swayed by every new fantasy imported from the complacent West. Additionally, we must implement sweeping changes to the personnel, structure, and processes of the security establishment—from the IDF to the ministry of defense—to make it more efficient and war-ready.

Even if one estimates that the chances of war are low, its potential impact is existential, making the risk very high. Moreover, there is always a significant possibility that such optimistic estimations are incorrect. Lastly, nothing deters enemies more effectively than preparedness for war. These fundamental truths have been forgotten in Israel. The rising generation has performed brilliantly on the field of battle, but as they rise to responsibility for planning for future wars, they must bear the onus of reclaiming these principles and use them as the foundation for a comprehensive overhaul of our security establishment.

Comments are closed.